Solutions to Reduce Systemic Inequities in Academia

Reported by:

Arianne Papa

Presented by:

Science Alliance

The New York Academy of Sciences

Overview

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, white males made up 53% of all full-time professors in 2018. And while the “STEM pipeline” is becoming more diverse–more than 40% of women and roughly 15% of people of color receive their PhDs in STEM fields–colleges and universities need to implement inclusive policies to initiate change on a large scale.

On October 9, 2020, the New York Academy of Sciences hosted a webinar with Georgetown University Medical Center affiliates to share their progressive efforts to decrease systemic inequities and improve workplace culture at their institution. In 2019, the university launched the Bias Reduction and Improvement Coaching (BRIC) program to raise awareness of unconscious bias and attenuate systemic barriers at institutions with the hope of promoting diversity and inclusion in STEM.

Highlights

- Bias impacts application, hiring, and promotion processes, as people make decisions based on shortcuts, unconscious preferences, and assumptions.

- The Bias Reduction and Improvement Coaching (BRIC) program brings together a group of individuals from various demographic backgrounds for training in the skills and language needed to raise awareness of bias.

- This “train the trainer” model empowers people to feel confident starting conversations about prejudice and how to mitigate bias in their respective departments and workplaces.

Speakers

Susan Cheng, EdLD, MPP

Georgetown University Medical Center

Kristi Graves, PhD

Georgetown University Medical Center

Caleb McKinney, PhD, MPS

Georgetown University Medical Center

Reducing Systemic Inequities in Academia

Unconscious Bias in STEM

Search committees looking to fill a job should be as objective as possible, especially when studies have shown that teams made up of diverse people are more innovative and high-performing. However, people rely on mental shortcuts and assumptions when making hiring decisions. They often use reflexive habits and exhibit unconscious preferences without realizing it.

Caleb McKinney, who trained as a microbiologist, transitioned to science education, and is now an Assistant Professor and Assistant Dean for Graduate and Postdoctoral Training and Development, related this phenomenon of reflexive habits to a “hot pot.” You learn from previous experience to pull your hand away when a stove is hot. With the same mindset, you can use your prior knowledge to make quick assumptions and form preferences about someone. He urged everyone to take an Implicit Association Test online to learn more about unconscious bias.

But how does conscious and unconscious bias impact STEM community development? Assistant Professor and Senior Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Susan Cheng, noted one example. STEM emphasizes innate intelligence over hard work, but in letters of recommendation, professors are more likely to refer to male scientists as “brilliant,” whereas female scientists are “productive.” The way a job description is written says a lot about what admissions may be looking for in a student or what faculty may desire during recruitment. Search committees may deem a person “not a good fit” for the institution. The only way to combat this is to use checkboxes to ensure job description criteria are followed systematically. “Implicit biases are always in the background, and you need to manage them actively,” said Cheng.

Kristi Graves, a clinical health psychologist and Associate Professor of Oncology, explained that bias also affects STEM professionals’ upward trajectories. For instance, scholarly productivity metrics are very numeric and usually include the number of papers published, impact factor for the journal in which you’ve published, and the amount of grant funding you’ve obtained. But faculty members don’t have access to the same opportunities. A male professor going to another male for a collaboration (because he is like him) is an example of similarity bias.

It’s critical to note that Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) make up a small percentage of faculty members. BIPOC faculty members often act as the representative BIPOC for diversity panels and mentoring groups, which takes time away from work and research. And the amount of time spent on essential work and research affects prospects for promotions. Graves believes that hiring committees should have explicit discussions about implicit bias throughout the year to increase faculty diversity. “Everyone has bias,” said Graves. “The trick is to try to become aware of the bias, and then when you notice it, you do something about it so the negative impact that flows from that bias is not sustained or perpetuated.”

Although many colleges and universities have increased awareness and implemented more inclusive policies, the culture has not shifted enough to facilitate a more diverse institutional community. Even representative images on posters and brochures should indicate that a university values different types of people in STEM and that the depicted individuals can serve as role models for scientists who want to know what the institution values.

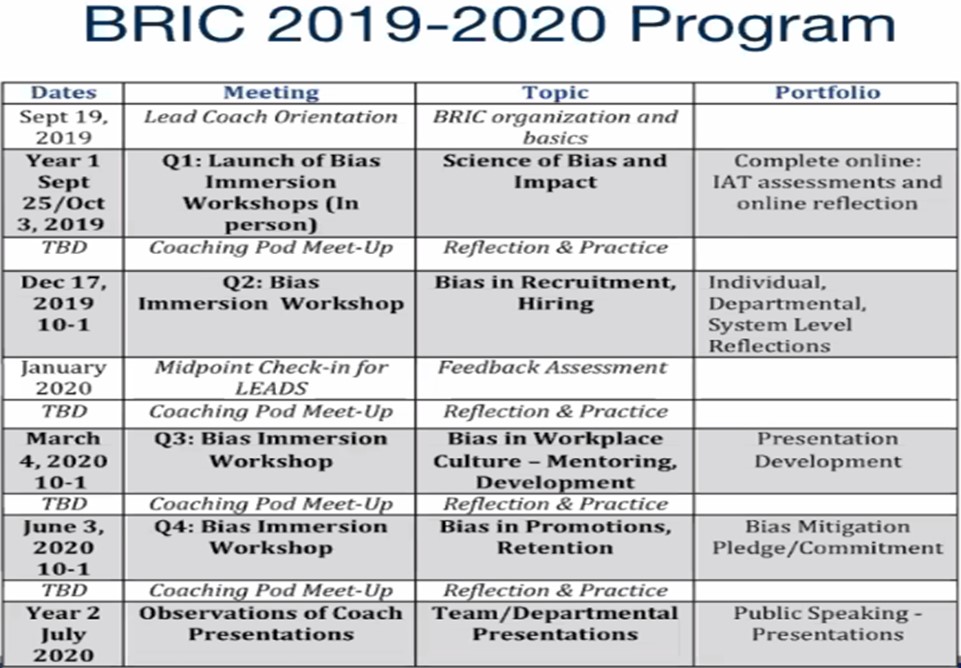

Understanding the BRIC Program

All three panelists have been heavily involved in the Bias Reduction and Improvement Coaching (BRIC) program at Georgetown University. The program leaders selected people from different backgrounds in various departments across the university for the program. Supervisor or departmental approval was required to participate since the program would take away hours spent on “numeric success metrics.” The inaugural group of 27 coaches—five of whom are coach leads—went through four, three-hour immersive sessions held quarterly. During these meetings, which covered the science of bias and its impact on hiring, promotions, retention, and overall workplace culture, participants learned evidence-based strategies to raise awareness and reduce discrimination. Participants led presentations and department talks on what they learned and received feedback from the coach leads.

The program’s goal is to have many people who can confidently initiate conversations about bias in their workplace. It is designed to establish training across the medical center by providing a faculty learning environment, explained Cheng. The messenger is so important because having the information come from a colleague you know and trust to understand the institutional context you work in is invaluable.

McKinney participated in the BRIC program and pinpointed three main attributes of the initiative. The training provided self-knowledge to reflect upon one’s personal bias, leadership skills to feel equipped to speak up about bias when necessary, and the ability to communicate these strategies when training others. Participants were asked to reflect on their time in the program and took surveys to assess its impact. Additionally, audience members from BRIC coaches’ presentations were surveyed to see if it was scaled to the department, and follow-ups were conducted to see if departments made any significant changes.

Program Outcomes

Although the initial training was geared toward faculty and staff, post-docs and graduate students organized bias reduction workshops and helped create presentations for their departments. Cheng believes that many students have already developed these skills, while faculty and staff are trying to catch up by participating in the available programs. In addition, departments are asking for workshops on microaggressions, anti-racism, and bias. Graves explained that the program built tremendous confidence for those presenting the material in a safe and confidential space. She also shared a reflection from a participant in the program who felt BRIC was “an effective approach to raise awareness about unconscious beliefs and attitudes and to discover biases in a non-confrontational manner.”

By bringing in participants from different sections of the medical center, the BRIC program facilitated collaboration between faculty and staff from various departments who would not typically work together. This teamwork increased cognitive diversity and allowed participants to build on each other’s thoughts in a broad group discussion. McKinney emphasized that BRIC fostered peer mentorship and feedback, and helped strengthen a sense of community throughout Georgetown University Medical Center.

He was impressed with how much he learned about himself while participating in the program. “To be truly empathetic, you have to be self-aware. You have to recognize and challenge the assumptions you may have about people and situations,” McKinney said. “The BRIC programs allows you to put yourself in other people’s shoes. You learn from each other how people’s experiences and backgrounds shape their individual context, and that’s so important for building empathy.”

Metrics for Success

The panelists shared an essential set of standards that needed to be met for the BRIC program to be successful. Most importantly, improving diversity requires commitment from everyone. That commitment starts with raising awareness and then addressing the issues to create a sense of belonging in the workplace. “Once people are more aware of these biases and start to engage in mechanisms to reduce those biases, you can really [assess an] environment that’s hostile and not welcoming,” said Cheng.

Graves sought feedback from leadership at Georgetown before starting the program. “Until you enact specific behaviors and policy changes, it doesn’t mean a lot,” she said. The institution is responsible for creating an inclusive environment for trainees, post-docs, and faculty and ensuring that people have equal opportunities to succeed. Establishing an inclusive environment doesn’t have to be a top-down method; valuable feedback can come from anyone.

Cheng also highlighted the importance of decisions and transparency. Critical decision making, which includes communicating news and defining expectations and limitations, should be collaborative. For example, department chairs should define a clear set of expectations, goals, and values before a selection process, and the selection committee should routinely review those criteria. “In STEM, we should be really good at creating objective definitions of how we know when we’ve made our goal,” said Graves.

In addition, all employees should periodically revisit training on inclusion and bias, not just at the onset of the job. McKinney advocated for structured mentorship for minority groups, including cross-cultural mentoring relationships. “Mentors from majority backgrounds have an opportunity to shape retention by fostering these welcoming environments for junior individuals to succeed,” he said. Mentorship also includes facilitating career identities for graduate students and post-docs. While it is critical to have support and map out your trajectory on an academic career path, mentors can also highlight opportunities in industry and focus on broad career paths.

The Future of BRIC

Bias awareness is critical now, when many interviews and meetings are being held virtually due to the pandemic. Graves saw this as a positive because it allows institutions to create new networks and reach students early on in their academic trajectories. They can reach a wider talent pool, and recruit candidates from various backgrounds who were not previously reached. Companies should also reassess their open opportunities because the way job descriptions are written and where they are posted plays an essential role in who applies. Equal opportunity statements at the end of job descriptions show candidates that a company values diversity and inclusion.

Georgetown University is not the only institution spearheading programs for systemic inequity awareness. Cheng praised numerous universities, such as UCLA, UCSF, and The Ohio State University, who have been at the forefront of implicit bias research and training. All three panelists are eager to continue the BRIC program. They hope that by scaling this bias awareness across Georgetown, there will always be individuals on committees who have been trained and can challenge their colleagues’ assumptions.

Further Readings

Misc

Dutt K, Pfaff DL, Bernstein AF, et al.

Gender differences in recommendation letters for postdoctoral fellowships in geoscience

Nat Geosci. 2016; 9(11):805-808.

Gibbs Jr KD, Basson J, Xierali IM, Broniatowski DA.

Elife. 2016; 5:e21393.

Sukhera J, Watling C.

A framework for integrating implicit bias recognition into health professions education.

Acad Med. 2018; 93(1):35-40.

Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G.

Blindspot: Hidden biases of good people.

Delacorte Press. 2013

Ross HJ.

Everyday bias: Identifying and navigating unconscious judgments in our daily lives

Rowman & Littlefield. 2014.

Harvard University.

https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/

Implicit Association Test. Project Implicit.

Unconscious Bias in Interviewing and Letters of Recommendation

https://som.georgetown.edu/diversityandinclusion/knowyourbias/biasintheworkplace/

Georgetown University School of Medicine

Know Your Bias

https://som.georgetown.edu/diversityandinclusion/knowyourbias/

Georgetown University School of Medicine.

Cobb J, Ali W.

https://www.aspenideas.org/podcasts/how-to-talk-about-race-and-racism

How to talk about Race and Racism. Aspen Ideas.