Taking a Trip with America’s LSD Research Pioneer

One of the first medical researchers to study LSD and other psychedelics cautioned against abuses. But also saw immense therapeutic potential.

Published January 20, 2026

By Nick Fetty

Well before it was embraced by the likes of Timothy Leary, Ken Kesey, and the Grateful Dead, Max Rinkel (perhaps unbeknownst to him) was laying the groundwork for what would become the psychedelic movement in the United States.

Rinkel was born in Germany at the end of the 19th century. He earned a medical degree from Christian Albrecht University in Kiel before emigrating to the United States. Early in his career he studied the use of Benzedrine in treating alcohol addiction. But by the 1960s, misuse of this amphetamine led to it falling out of favor with the medical community.

He also studied the use of Pervitin, another amphetamine, as a “truth serum” for treating patients with psychiatric disorders. Pervitin was used by the Nazis during World War II. It enabled “soldiers to march and fight for days at a stretch without needing to rest or eat” while giving the user feelings of optimism and euphoria. Similar to Benzedrine, the potential for misuse led to Pervitin losing credibility within the medical community.

Dr. Rinkel’s big break came in the late 1940s, when he began studying the use of another substance, discovered in a Swiss lab roughly a decade prior, for dealing with psychiatric disorders.

Turn On, Tune In, and Study

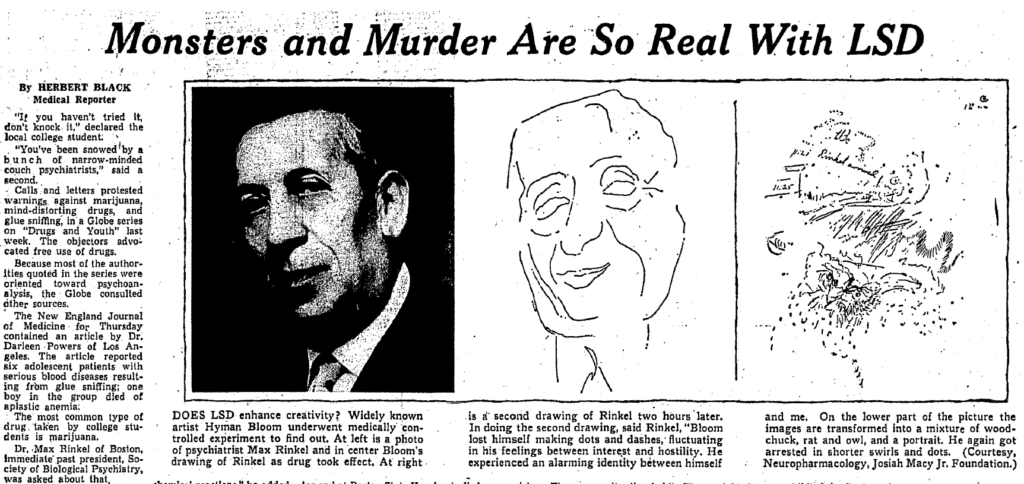

The Harvard Crimson cites Dr. Rinkel as “the first doctor in North America to work with LSD,” when he supervised his research partner who in 1949 ingested the substance and experienced “the first acid trip in the West.” (“Acid” is used as an informal or street term for LSD.) In a related experiment that same year, Dr. Rinkel administered LSD to modern American painter Hyman Bloom, who reported that it heightened his awareness.

“It was really a great experience for me,” Bloom told The New York Times. “On the other hand, it was more difficult to draw. My control was reduced, or lacking. I was interested, however, in the philosophic aspects of LSD as a religious experience.”

This sentiment was echoed by Dr. Rinkel who observed a positive change in Bloom’s mood, but not in his artistic ability, while under the influence of LSD.

“There is no doubt that the drug put him in ecstasy,” Dr. Rinkel said as reported by the Associated Press. “But the drawings he produced were mainly unformed, and when formed were monstrous creatures.”

Dr. Rinkel, who at least once dropped acid himself in a controlled environment and stated “the experience was not always pleasant,” shared one challenge he encountered with his research subjects during the 1951 American Psychological Association Convention in Cincinnati.

“In the LSD test situation,” he stated, “subjects appeared more interested in their own feelings and inner experiences than in interacting with the examiner, confirming behaviorally the test results, which indicated increasing self-centeredness.”

An Evenhanded, Scientific Approach

This early work predated Timothy Leary, PhD, a fellow Bostonian, who would advocate for LSD beyond just its medicinal properties, in the 1960s. However, unlike Dr. Leary, who was an advocate, Dr. Rinkel was more objective and scientific in his assessment of LSD’s potential.

In 1965, Dr. Rinkel studied the aftereffects of LSD on students in Boston who were dealing with anguish, anxiety, and pain. Part of his conclusion was that unregulated, black-market LSD taken outside of controlled settings can be dangerous for users because of variations in the drug’s purity and dosage. During this era, students in his study reported that LSD could easily be obtained from street dealers on Harvard Square for about $5 per dose. Furthermore, Dr. Rinkel found that LSD’s effects can exacerbate problems for individuals who have neurotic and latent psychotic tendencies.

However, despite these cautions, Dr. Rinkel saw immense potential for LSD when administered within a controlled environment. With illicit use on the rise, states began prohibiting possession of LSD in 1966. By 1970 President Richard Nixon (who once called Dr. Leary “the most dangerous man in America”) signed the Controlled Substances Act, which prohibited psychedelics at the federal level. While Dr. Rinkel was sensitive to these abuses, he also felt controlled research was necessary to better understand LSD’s properties and to avoid future abuses.

“An Excellent Tool for Research in Biological Psychiatry”

“It has proved an effective tool for research, and has stimulated widespread investigations into the possible biological causes of mental illness,” Dr. Rinkel told the Boston Globe in 1965. “It has been proposed as a cure for alcoholism, and a therapeutic aid in narcotic addicts. It is being used in the study of autistic (self-centered) schizophrenia [sic] in children. It is being studied for possible use in easing intractable pain in terminal cancer cases.”

He further reiterated this position in a paper published a year before his death.

“Responsible research with LSD and similar substances by ‘qualified’ physicians and scientists is, however, vital and must go on,” Dr. Rinkel concluded in a 1965 article published in The Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Convention and Scientific Program of the Society of Biological Psychiatry. “Uncontrolled and uncritical experimentation should not be allowed to create an [sic] hysterical attitude which would further hinder or obstruct legitimate experimentation with LSD, an excellent tool for research in biological psychiatry.”

Though historical records do not provide a precise date, Dr. Rinkel attained the rank of Fellow with The New York Academy of Sciences. At this time, Fellows were selected by sustaining and active members for the virtue of their scientific achievement. Dr. Rinkel passed away in 1966 at the age of 71.

A Long, Strange History

While Dr. Rinkel might be the earliest connection, the Academy has a history with research around LSD and other psychedelics with therapeutic potential. Psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond and author Aldous Huxley put their heads together to come up with a term that described the effects of LSD. It was during a meeting at The New York Academy of Sciences in 1957 that the term “psychedelic” was believed to be first used in a public setting.

Promoting work and research around psychedelics continues to be a focus of the Academy now in the 21st century. In 2021, the Academy hosted a webinar titled Psychedelics to Treat Depression and Psychiatric Disorders, and two years later hosted a conference focused on near-death and psychedelic experiences. These events garnered the attention of external media outlets like Scientific American, Discover Magazine, and Big Think.

Having laid the groundwork, Dr. Rinkel might be proud of the current state of research and even legislation on psychedelics in the United States. Nicolas Langlitz, MD, PhD, who oversees the Psychedelic Humanities Lab at The New School, contextualized the current state of psychedelics research on a recent episode of the Academy’s Shaping Science podcast. In an effort to appease both sides of the political aisle, Dr. Langlitz, who similar to Dr. Rinkel was born in Germany and earned a medical degree, pointed out that researchers and lobbyists deliberately moved away from the counterculture element. Instead, they focused on using psychedelics to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which often impacts veterans and law enforcement officers.

“The interesting part about the psychedelics renaissance is that in this hyperpolarized political environment, psychedelics were one of the very few topics that received several bipartisan bills in Congress,” Dr. Langlitz said.