The Academy’s new home on the 40th floor of 7 World Trade Center will convey our distinguished heritage while also establishing an efficient environment for new ideas.

Published July 1, 2006

By Hugh Hardy

In 1950, a mansion on East 63rd Street was the answer to The New York Academy of Sciences’ (the Academy’s) dreams. With its sixteenth-century Italian mantel in the entry hall and a library of carved English oak, the building exuded an air of old-world scholarship and elegance that suited members and impressed visitors.

Today, however, the Academy needs more office and meeting space than the mansion can provide. What’s more, the building’s traditional interiors and furnishings give no hint of the Academy’s progressive nature and mission. Rather than shrink from change, as its current rooms dictate, this institution embraces it. This outlook will become astoundingly clear when members make their first visit to the Academy’s new home, forty stories in the air, at 7 World Trade Center. With spectacular urban and water views from all points of the compass, this aerie will dramatize the institution’s central role in New York’s scientific life and signal its vitality to visitors who come from around the world to participate in its activities.

Of course, the Academy is not abandoning its traditions. Science is built upon the work of previous generations and on many legacies of investigation and thought, even as it crosses frontiers into the unknown. This project’s design challenge lies in conveying the Academy’s distinguished heritage while also establishing a contemporary and efficient environment for its forward-looking activities.

A Magnificent Blank Slate

The Academy looked for space in many older office buildings, where it would have had to make decisions about what lobby space, offices, and conference rooms to keep and what to change. Instead, by renting (on advantageous terms) the entire 40th floor of a spanking new building, the organization was presented with an expanse of raw space, a magnificent blank slate. Seven World Trade Center is the only structure in the city whose floor plate is a parallelogram from bottom to top, and it offers 28,000 usable square feet per floor, without a single column between its central core and its perimeter walls of glass.

Our floor plan for the Academy bisects the building’s parallelogram on a north-south axis to accommodate two basic functions, one private, one public. The eastern portion is devoted to public areas, containing a lobby, reception space, three meeting rooms, “breakout” areas, and the president’s office. The western half of the floor contains offices for the staff and support areas.

The Academy’s links to the past are made clear in the entrance lobby, where a monumental bronze bust of Charles Darwin, which long graced the Academy’s garden, is prominently displayed to the left of the entry. Behind the reception desk is a sculptural metal “art wall.” Its openwork filigree echoes nineteenth-century street patterns and illustrates the Academy’s three original downtown locations. This patterned surface forms a sloping wall, dividing the entrance lobby from a generous socializing space by the windows. From here, views of Lower Manhattan will astonish visitors. At this vantage point, flatscreen monitors will direct participants to their meeting areas, announce current activities, and present the latest multimedia web offerings from www.nyas.org.

A Focus on Flexibility and Sustainability

Conferences and meeting presentations require concentration, without the distraction of fascinating views. Therefore, three meeting rooms are fashioned so that each can shut out the panoramas. One of the conference rooms, shaped like a pod, is totally enclosed, while the others have shades that can hide the view. Groups from 30 to 300 people can be accommodated.

To the northeast, in one of the wide corners of the parallelogram, movable walls provide further flexibility, permitting corridors to be joined with the largest presentation room. A pantry permits catered food service for special events. Throughout the project, we worked with the goal of flexibility, knowing that activities will change within rooms from hour to hour, day to day.

Green concerns informed our planning. Lighting zones are monitored by motion sensors, and lights turn off after an allotted time if no one is present. Photometric sensors tied to westernmost lights automatically turn lights off during bright afternoon sunlight. In addition, almost all of the lighting is energy efficient fluorescent. Carpet tile is being used to reduce waste.

If areas of the carpet wear out over time or are stained, only those tiles need to be replaced instead of an entire run of carpet. The desk chairs are 44 percent recycled and 99 percent recyclable, and offices and workstations use high proportions of recycled materials, including steel paneling and mineral board, and glues and finishes that do not contain volatile organic compounds. Fabric for all of the upholstered walls and cubicles is 100 percent recycled polyester.

Combining Utility and Aesthetics

This institution has long held art in high esteem, using many forms of expression to suggest the shared interests of artists and scientists. An 80-foot-long gallery runs the length of the building’s interior core and will contain artworks relating to the Academy’s programs. Photographic panels, designed by the graphics firm 2×4, will decorate the conference rooms.

Those large images—some in black-and-white, some in color—depict details of the natural environment as seen through an electron microscope, as well as flowers distorted by anamorphic projection. The Academy’s new interior design utilizes materials that juxtapose tradition with innovation. We custom-designed a red carpet woven with a decorative gray-and-blue version of the DNA double helix. The carpet will offset paneling of light-colored wood.

After the Academy’s move this fall, visitors will enjoy a distinctive new facility that will encourage communication, discovery, and the generation of research and ideas. The Academy’s physical transformation represents its confidence in the future and its prominent role in the scientific and intellectual leadership of New York.

Learn more about the Academy’s history.

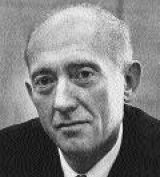

About the Author

Hugh Hardy and his firm, H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture, are designing the space. Among Hardy’s well known projects in New York are the redesign of Bryant Park, the visitor center at the New York Botanic Garden, and the restoration of the BAM Harvey Theater.