Acts of Congress, research studies, passionate scientific community leaders, and a new Academy initiative all aim to stem the collapse of American STEM education.

Published March 1, 2010

By Alan Dove, PhD

On October 4, 1957, a rocket launched from the steppes of Kazakhstan delivered the first artificial satellite into Earth’s orbit, giving the Soviet Union an early lead in the defining technological competition of the Cold War. In response, a new generation of American students rushed into careers in science and engineering. Less than 12 years later, this home-grown talent pool helped land the Apollo 11 spacecraft on the moon, planting the Stars and Stripes in lunar soil and establishing the dominance of American science.

Or not.

The Sputnik story has become one of the most enduring myths in American science education, but it’s mostly fiction. While Sputnik did spark widespread public fear and inspire a strong political response in the form of the National Defense Education Act of 1958, the actual number of science and engineering enrollments at colleges remained virtually flat throughout the 1960s. Instead of a homegrown talent pool, the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs relied heavily on engineers educated in Europe. The Apollo landing was a thoroughly impressive engineering feat, but it produced little new science.

Indeed, as a long succession of international studies and government reports have argued, American science education largely stagnated after World War II: The average American public school graduate is scientifically illiterate, they say.

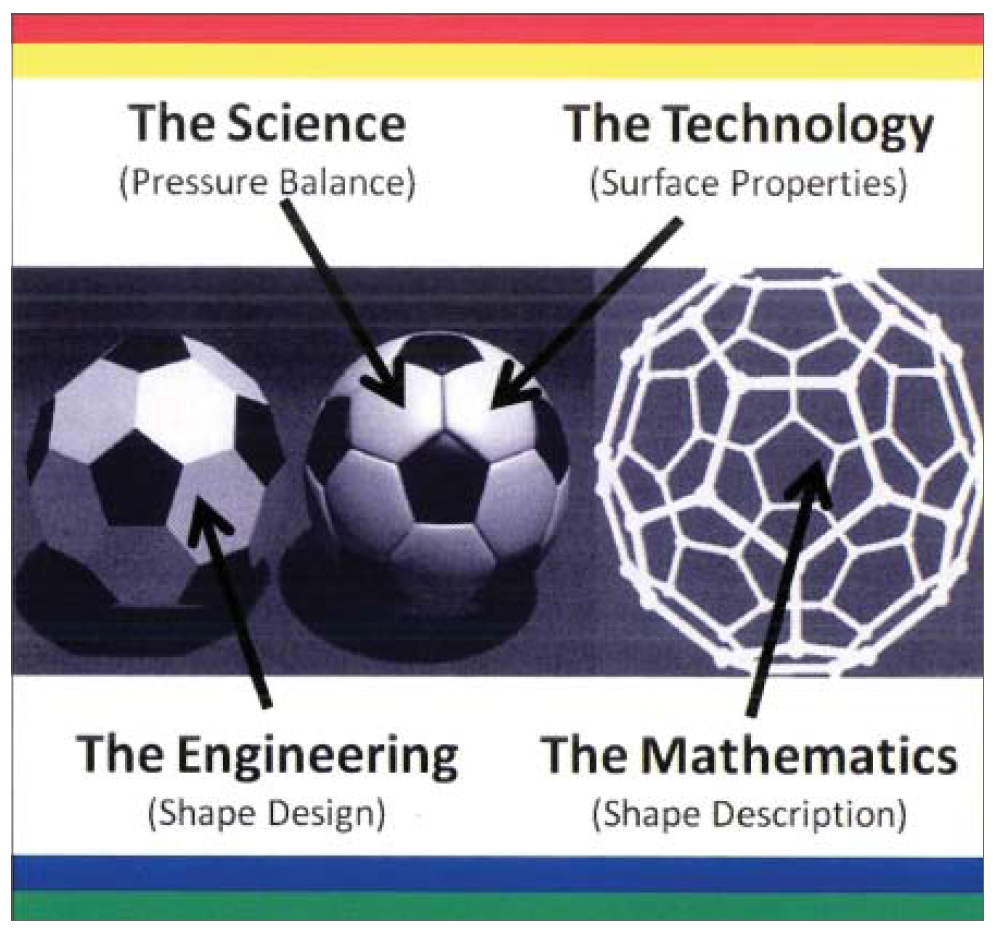

On October 23, 2009, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan addressed President Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, citing disturbing statistics about the state of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education in the United States: “In science, our eighth graders are behind their peers in eight countries… Four countries—Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Finland—outperform U.S. students on math, science and all other subjects.”

Closing the Achievement Gap

Secretary Duncan outlined a number of goals that must be reached in order to close the achievement gap and improve American students’ comprehension of the STEM disciplines. Aided by this new Federal push for STEM education, experts from diverse fields and political viewpoints are now trying to address the longstanding failure. In the process, they are asking fundamental questions about the way America educates its citizens: how worried does the U.S. need to be about science education, why has it been so bad for so long, and what can be done to improve it?

Anyone studying American science education must immediately confront a paradox: despite decades of documenting its own weaknesses in science education at the K-12 level, the nation has remained a world leader in scientific and technological achievement. If the U.S. is so awful at teaching science, why are Americans still so good at practicing it?

One explanation is the time lag inherent in scientific training. “I’ve always called the whole situation the quiet crisis,” says Shirley Jackson, President of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, NY. “It’s quiet because it takes years to educate a world-class scientist or engineer. It starts with the very early educational years and goes all the way through levels of advanced study,” she says. As a result, problems in the public school system could take a generation to manifest themselves in university laboratories and corporate R&D campuses.

Imported Talent

Imported talent also masks the issue. “After World War II something like 70 percent of the world’s economic output was centered here in the United States,” says Jim Gates, professor of physics at the University of Maryland in College Park. “That meant that as a society we could count on the brightest minds from around the world seeking opportunity to come to us because we were the place where the most opportunity was apparent.”

In recent years, though, educators have begun worrying about two additional trends. “There are stories of very talented colleagues from Asia who have essentially decided to repatriate either to India or China…and this is a phenomenon I think we’ve seen in academia increasing for the last several years,” says Gates. At the same time, emerging economies such as China and India have made enormous investments in science and engineering education in order to mine rich veins of talent in their immense populations.

It’s been a hard threat to quantify, though. The 2005 National Academy of Sciences report “Rising Above the Gathering Storm” presented some attention-grabbing statistics. For example, the report asserted that in 2004 China graduated 600,000 new engineers, India 350,000, and the U.S. only 70,000. However, the committee’s methods for deriving those figures came under fire from critics who pointed out that the definition of “engineer” varied considerably from one country to another. Correcting that error halved the number of Chinese engineers, doubled the American number, and showed that the U.S. still had a commanding lead in engineers per capita.

Choosing Careers Outside of Science and Engineering

More recently, a report released in October 2009 by investigators at Rutgers and Georgetown argued that U.S. universities are graduating more than enough scientists and engineers, but many choose jobs outside of their major field. According to that report, which was sponsored by the Sloan Foundation, the perceived shortage of technical expertise is more likely due to American companies’ unwillingness to pay for it.

That viewpoint has its critics, of course. “I’m well familiar with the Sloan study, but what we’re really talking about is innovation capacity,” says Jackson, who helped write the 2005 National Academy report. She adds that the real problem will manifest itself over the next few years, as the first rounds of baby boomers begin to leave the workforce. “We have a population of people…from the various sectors who are beginning to retire, and those retirements are beginning to accelerate.” While current employment statistics might show plenty of scientists and engineers for available positions, Jackson and others expect the impending retirements to alter that.

While debate about whether the U.S. is adequately training the next generation of professional scientists rages on, it’s hard to disagree with those who argue that the country needs to improve the scientific literacy of its lay public. “We seem to accept that people need to be able to read and write in order to be educated, to be able to function in society, and that is obviously critical, but what we have to also recognize is that people need certain baseline mathematical skills and some knowledge of science and technology in order to be literate,” says Jackson.

A Scientifically Literate Public

Gates concurs: “Having a scientifically literate public is going to be critical as our nation wrestles with problems whose solutions seem inherently to involve science and technology.” In particular, he cites climate change, where scientists have had considerable difficulty explaining a well-established phenomenon to politicians and citizens who have little understanding of basic math and physics. “Having a public that is scientifically illiterate doesn’t bode well for the future of our country,” he says.

Other education reform proponents are more blunt. “I regard the collapse of math and science education as the greatest long-term strategic problem the United States has, and likely to end our role as the leading country in the world,” says former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich.

Famous for engineering the 1994 Republican Congressional victories, Gingrich, a former college history professor, is outspoken about the need to reform a public education system that he says values certification over knowledge. “We…don’t have physicists teaching physics, we don’t have chemists teaching chemistry, and we don’t have biologists teaching biology,” he says.

Highlighting the political breadth of the issue, Gingrich recently accompanied Education Secretary Duncan and Reverend Al Sharpton on a tour of high schools in Philadelphia. Despite their radically different positions on other issues, the three agreed that American science education urgently needs help.

Others point out that improving public science education is also a prerequisite to training more scientists. “Without that…educational base, we don’t have the base to draw indigenous talent from, talent that may then actually become the next generation of scientists and engineers, so they’re two issues, but they are linked,” says Jackson.

Resistance is Feudal

There is no shortage of potential causes for the nation’s scientific ignorance. Indeed, critics of the educational system often focus on whichever problems seem most relevant to their agenda. Advocates of charter schools like to point to powerful teachers’ unions and administratively bloated school systems. Privatizing education with charter schools, they argue, would give these bureaucracies nimble, efficient competition, forcing the public system to reform or die.

Others emphasize staffing problems instead, such as the tendency for science teachers to have majored in education rather than science, and a transient labor pool in which a third of K-12 teachers leave the profession within five years of being hired. In their view, both public and charter schools must draw and retain more highly trained science teachers.

Still others point to the balkanization of the American educational system, which allows each state and even each school district, wide latitude in setting curricula and standards. “Most developed countries have not just national tests, but national curricula,” says Gates. “We can’t say that the quality of education can differ in California and New York versus Wyoming and Florida,” he adds. “We want to have a common, internationally competitive set of standards.”

Getting more than 14,000 school districts in 50 states to agree on those standards, however, remains difficult. Gates has seen the problem firsthand from his seat on Maryland’s school board. “School boards and superintendents basically have their own feifdoms,” he says.

School districts aren’t the only feudal systems. Getting the national-level education agencies to coordinate their activities has been a tall order. An analysis by the Department of Education found that in 2006, a dozen different Federal agencies spent a total of more than $3 billion on science education initiatives, but a lack of coordination often made the efforts redundant or counterproductive.

The America COMPETES Act of 2007

To address some of these problems, Congressman Bart Gordon, D-TN, introduced the America COMPETES Act of 2007 which, among other things, established the Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarship. The fund, which Congress endowed with $115 million this year, encourages math and science majors to become teachers, and current math and science teachers to go back for more training. “We found that a very large percent of our teachers who teach math and science have neither certification nor a degree to teach those two subjects, so we have set up programs to help with that competency,” says Gordon.

Gordon, who chairs the House Committee on Science and Technology, also wrote the STEM Act of 2009. That bill aims to improve the coordination of Federal STEM education efforts and make them more user-friendly. “We did some digging and found that there were a number of STEM education programs all across the Federal government…that you couldn’t find just by looking down a table of contents, you really had to dig in, and so we felt that by having better coordination, that we would be able to get better leverage there,” says Gordon. The STEM Act passed the House in June and is now awaiting action in the Senate.

Besides streamlining the system, national standards and more unified Federal efforts could help nip some antiscientific trends, such as creationist school boards that attempt to undermine the central organizing principle of biology. American creationists, who preach a literal interpretation of the Bible, have often aligned themselves with conservative Republicans for political leverage.

Reducing the Attention Deficit

The party is not of one mind on the issue, though. “There have been four parallel evolutions of sabertoothed cats over the last 40 million years…and you can see literally almost the exact same steps of adaptation. Now, it’s very hard to look at that and not believe some kind of evolution occurs,” says Gingrich. He adds that the lesson for educational policy is equally obvious: “I have no problem with creationism being taught as a philosophical or cultural course, as long as you teach evolution as a science course, because I think they’re two fundamentally different things.”

Winning the argument for evolution in biology is only a small step toward reforming STEM education nationwide, though. Indeed, some critics of the current system advocate widespread and radical changes. Gingrich, for example, suggests incentive programs to pay students for performance: “I propose in every state that we adopt a position that if you can graduate a year early, you get the extra cost of your 12th year as an automatic scholarship to either [vocational] school or college.”

Others advocate much faster adoption of technology in the classroom. Jim Gates says the average modern science classroom has few technological advances over the classroom of 50 or 60 years ago. Instead of continuing to rely on textbooks and chalkboards, he suggests switching to electronic texts and presentations, and allowing teachers to download new material instantly as it becomes available. “We have this incredible technology that’s remaking the world around us…and to think that somehow education will be untouched by this revolution…is extremely naive,” he says.

Past Reform Efforts

Radical innovations certainly sound interesting, but the history of past reform efforts in American science education provides a sobering counterpoint. Early in the Clinton administration, for example, the National Science Foundation (NSF) launched an ambitious program called Systemic Initiatives to help whole school systems make large-scale changes in science education. The initiatives achieved some notable successes in boosting science achievement, particularly in poor rural and urban districts.

Then, in 2002, Congress passed a mammoth set of reforms called No Child Left Behind (NCLB). To fund NCLB projects, the NSF had to drain $160 million from the Systemic Initiatives budget, effectively sidelining the program less than 10 years after it had begun. NCLB, in turn, has been widely panned by educators, politicians, and scientists. Critics argue that NCLB’s heavy emphasis on standardized testing has encouraged states and school districts to manipulate the tests rather than make genuine improvements. Because of this, NCLB is now set for its own overhaul, potentially shifting the science education agenda yet again.

This time, though, reformers have brought a new constituency into the discussion: state governors. Aided by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the National Governors’ Association has now developed a STEM Education initiative, including grants to fund reform efforts in individual states. Such state-level programs could go a long way toward improving the system nationwide if they are properly coordinated. “We need to think about what can be done to knit together the range of activities across the local, state and Federal level that involve public, private, and academic sectors, and that’s a challenge,” says Jackson.

An Interesting Trend

Scientists and engineers can also take heart from an interesting trend in college data: while the Space Race had little effect on the number of new enrollments in these fields, they spiked in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Various commentators have suggested that students were following an altruistic urge to solve pressing environmental and energy problems, which were just coming to the fore then, or that they simply wanted to improve their employability during an epic recession.

In either case, history seems primed to repeat itself. Both environmental degradation and skyrocketing unemployment are making headlines again, and science and engineering enrollments are once again on the rise.