Imagine if we could detect health problems before they become life-threatening.

Published June 04, 2021

By Benjamin Schroeder, PhD

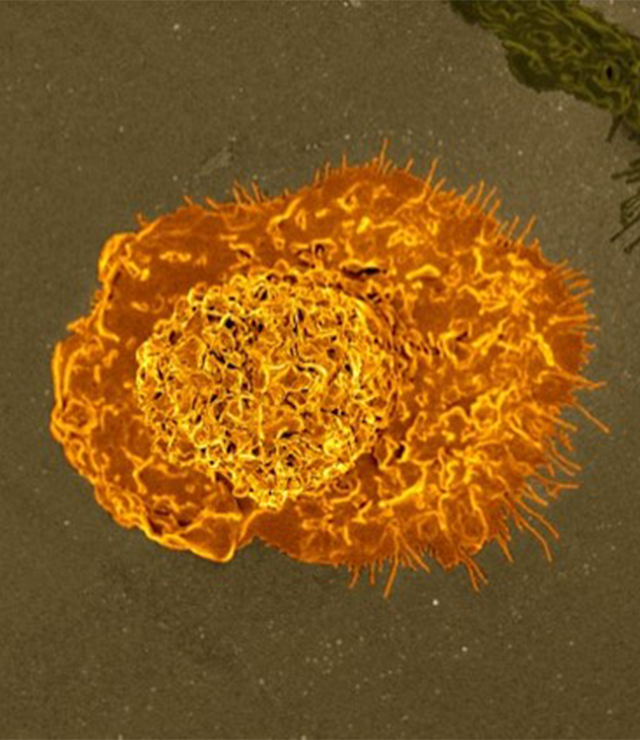

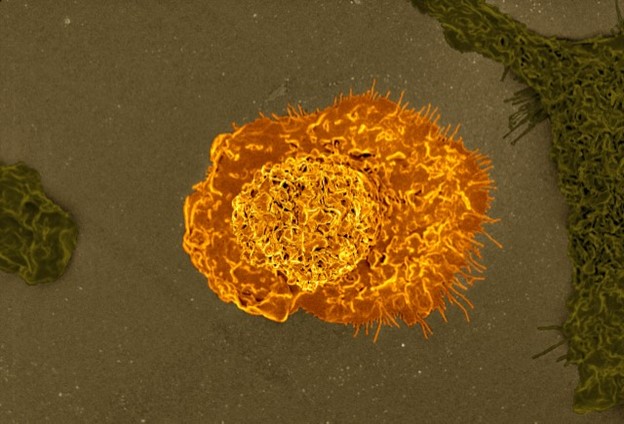

Imagine if we could charge our cell phones by plugging them into our backpack, or if we could build a biocompatible probe that could interface with our cells and detect health problems before they become life-threatening.

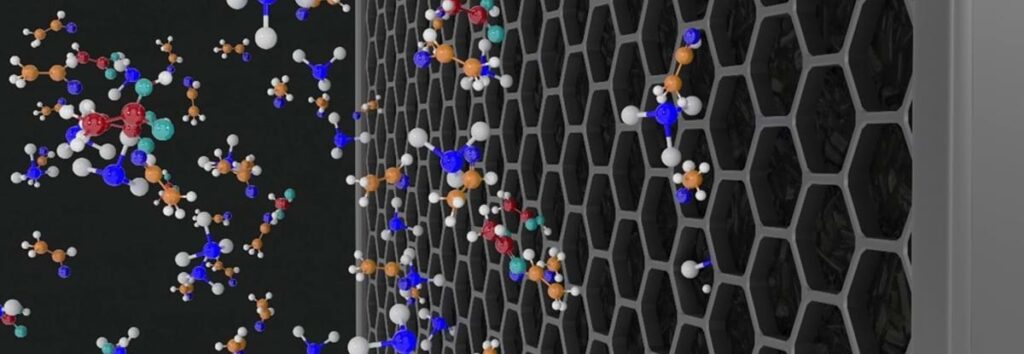

Working at nanoscale, scientists are now capable of assembling molecules and atoms into structures that have exactly the desired properties they want a new material to possess. The prefix “nano” is used in the metric system to describe 10-9 parts of a whole, or 0.000000001—an exceedingly small number. But the term is also used to define an entire field of new and exciting research at a very, very, tiny scale.

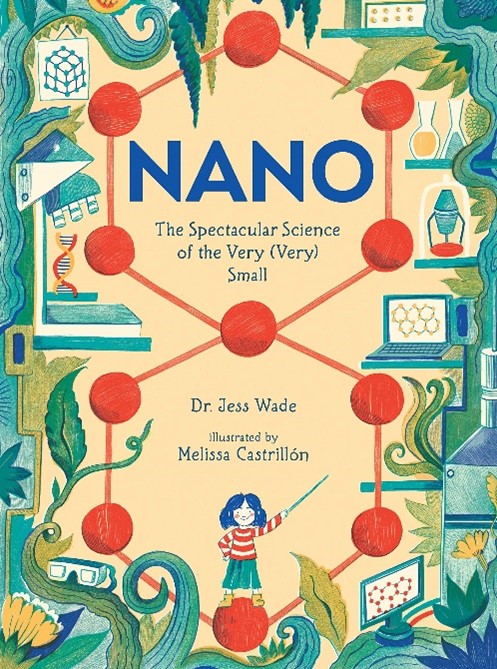

We recently interviewed Jess Wade, PhD, a Research Fellow at Imperial College London, about all things nano. Her research is focused on new materials for optoelectronic devices, with a particular emphasis on chiral organic semiconductors. She has also recently written a children’s book entitled Nano: The Spectacular Science of the Very (Very) Small, illustrated by Melissa Castrillon and published by Candlewick.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Many researchers in your field of materials science are drawing inspiration from nature to design new nanomaterials with novel shapes and functions. Why is that such an important consideration?

Because nature has been nailing this for a really long time. We look around and see naturally occurring structures that are super-strong, super-efficient, and in some cases capable of generating clean energy from the sun. I think we—as physicists, chemists, and materials scientists—can learn a lot from looking at natural, biological forms and trying to recreate their desirable properties in our labs.

Nature has evolved to be as efficient and streamlined as it can be, and we’re learning from that and applying it in areas like renewable energy and electronic display research. It is important for us to study those systems because nature has been getting it right for much longer than we have!

If nature has perfected processes like photosynthesis and cellular respiration, is it really possible to improve on nature’s design when creating new nanomaterials?

Molecules like proteins and peptides and similar compounds are essential in biological processes, but often have very strict operating requirements: they don’t behave normally when they get too hot or when they get very, very cold or when we put them in electromagnetic fields. So we can look at biological systems, examine what gives rise to their important properties, and ask, for example, “how can we design more resilient materials for technological purposes?”

I think even though nature has really perfected certain materials and processes, it has only really done so for a specific function. We can still improve these natural materials by tailoring them to what we want.

In terms of discoveries that will potentially have a major influence on our daily lives, what are some of the breakthroughs in nano that you anticipate seeing in the next 15-20 years?

In 15-20 years more of us will have solar technologies that result from manipulation of the nanoscale properties of materials. For example, take materials like perovskites: hybrid organic/inorganic crystals that are incredibly efficient at generating electricity when they absorb light from the sun. Once scientists have optimized their nanostructures and fabrication protocols, perovskites will allow us to have flexible, integrated power supplies that can be incorporated into our clothing, our backpacks, and any surface that might be beneficial. I think there will also be a more concerted effort for scientists to work closely with designers to create wearable devices and other technologies that combine aesthetics with cutting-edge science.

You’ve just published a beautifully-illustrated children’s book entitled, Nano: The Spectacular Science of the Very (Very) Small. What was your inspiration to write such a book, and can we expect to see additional children’s books from you covering different topics in science?

I find the science that you’re covering in the upcoming webinar “Finding Inspiration for Functional Nanomaterials from Nature,” and the nanoscience that I get to do in my day job extraordinarily exciting. Parents, students, and teachers don’t get quite as excited about it as they could because it’s not on their radar, and they get intimidated by jargon and buzzwords they do not really understand.

I wanted to write a book that young people read and then think, “chemistry is really cool! materials science is awesome! we can solve the global challenges by thinking from the atom up!,” but also a book that their parents read and think, “hey, maybe I was wrong to hate that so much when I was in school.”

I would absolutely love to create additional children’s books. There are a lot more areas of science that could have kid’s books. Dinosaurs are covered, space is covered, but there could be more and better coverage in physics and other areas, and I am excited about the possibilities.