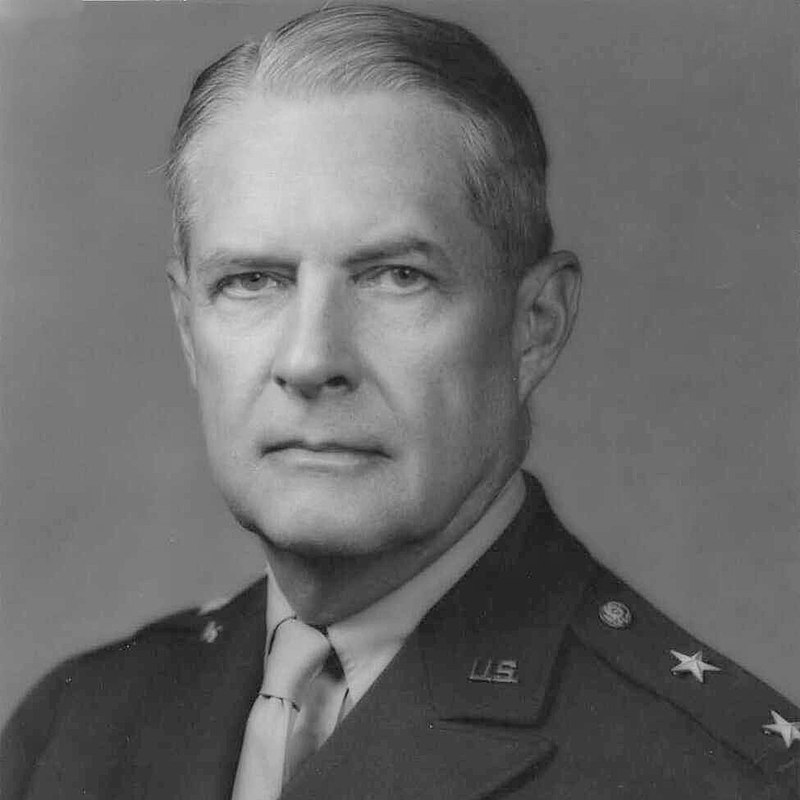

Ulysses S. Grant is best known for leading the Union Army to victory during the American Civil War and serving as the nation’s 18th president, but his less-well-known grandson, who was an associate member of The New York Academy of Sciences, had his own impact on the country in the fields of civil engineering and architecture.

Published November 11, 2025

By Nick Fetty

Ulysses S. Grant, III, was born in Chicago in 1881. He eventually moved to New York City and studied at Columbia University. Grant briefly served during the Spanish-American War, prior to being admitted to West Point Academy, his grandfather’s alma mater. At West Point he was classmates with Douglas McArthur. MacArthur, who became America’s top general during World War II, graduated first in the class of 1903, while Grant was sixth.

Army Corps of Engineers and World War I

Upon graduating from West Point, Grant briefly served with the Army Corps of Engineers in the Philippines, Cuba, and Mexico. There he received formal training and education in engineering. He also served as an aide to President Theodore Roosevelt. It was at the White House that he met his future wife, Edith Ruth Root, daughter of Eilhu Root who served as Secretary of War and Secretary of State in the McKinley and Roosevelt administrations.

During World War I, Grant served as secretary of the American section of the Supreme War Council in Paris. Along with U.S. General Tasker H. Bliss, he played a role in negotiating and writing the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the war. Grant was promoted to the rank of Colonel and received the Army Distinguished Service Medal in 1919.

A statement from the War Department lauded Grant for his specific contributions: “As Secretary of the American section, Supreme War Council, Colonel Grant was entrusted with the most important duty of coordinating the work of the Joint Secretariat of the Supreme War Council and of the Joint Secretariat of the Military Representatives of the Supreme War Council, and as a member of the War Prisoners’ commission, Berne, Switzerland, he has rendered conspicuous service to the Government.”

Civilian Service and World War II

Between WWI and WWII, Grant returned stateside spending time in Washington, D.C. and San Francisco. During this time, he was promoted to the rank of Major. He worked as the executive officer of the Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission, a member of the National Capital Parks and Planning Commission, and eventually as the leader of the Office of Public Building and Public Parks in Washington, D.C. He continued to climb the military ranks, rising to Lt. Colonel and then Brigadier General.

When the U.S. entered World War II following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Grant was named Chief of the Protection Branch of the Office of Civil Defense, overseeing the civil defenses of the entire United States.

An already decorated veteran, Grant added to his accolades after the war, which included the Croix de Guerre (French for “war cross”), an honor bestowed upon French allies during both world wars; the Legion of Honour, the highest distinction that can be conferred in France on a French citizen as well as on a foreigner; and the Legion of Merit, bestowed by the U.S. Armed Forces to an individual who “has distinguished himself or herself by exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievement.”

Grant formally retired from the Army in 1945 with the rank of Major General.

Later Years

Despite hanging up his military uniform, Grant wasn’t ready to stop working. He served as vice president of George Washington University in Washington D.C. from 1946 to 1951. Though relatively little is documented from his foray into higher education administration, the university hosted an exhibit in 2023 recognizing the Grant family’s contributions to the museum. The exhibit, titled Rethinking Legacy and Memory: Behind the Image of Ulysses S. Grant, focused on the elder Grant and his legacy outside of his militaristic and political leadership.

The younger Grant was also an associate member of The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy), meaning that despite moving away from New York he chose to remain affiliated with the Academy.

In his final years, Grant took an interest in history preservation. He served on the Civil War Centennial Commission and authored a biography of his grandfather. Ulysses S. Grant, III, passed away in 1968 at the age of 87. The elder Grant, who passed away in 1885, did not live long enough to see his grandson pursue a career of service to his country much like he had done roughly half a century earlier.

Also read: From Surveying Railroads to Designing Durable Clothes