Medical advancements around stem cells are often covered in the news these days, but what is a stem cell? Learn more about the science and potential of these versatile cells from our conversation with Donald Orlic, researcher with the National Institutes of Health.

Published September 1, 2001

By Levin Santos

It has been grabbing headline news everywhere. Embryonic stem cell research has been politicized but the battle lines are blurred; staunch antiabortionists are siding with liberal Hollywood stars to pressure President George Bush to approve federal funding for human embryonic stem cell research.

How stem cells work is still largely unknown. Much of the promising work has thus far been done on the less controversial adult stem cells. Donald Orlic, member of The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy) since 1984, is trying to unravel the mystery. He is a staff scientist at the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health in Maryland. His work has been described more fully in Volume 938 of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences: Hematopoietic Stem Cells 2000: Basic and Clinical Sciences.

What are you presently working on?

My interest during these years at NIH has been in the area of adult bone marrow stem cell research. I’ve been interested in purifying hematopoietic or bone marrow stem cells and also studying their cell biology, especially with respect to gene therapy. So I spent a number of years working on questions of improving gene therapy in bone marrow stem cells. More recently, I’ve become interested in what is defined either as stem cell plasticity or transdifferentiation.

What is plasticity or transdifferentiation?

Bone marrow stem cells were previously thought to produce mature blood cells and that’s all. They’re now known to have the capacity to produce nerve cells, skeletal muscle cells and cardiac muscle cells, as well as epithelium and blood vessels throughout the body. It is this ability that is described as plasticity. It’s a form of differentiation that heretofore was not recognized. Instead of being limited in their ability to form mature blood cells, we now see that these bone marrow stem cells have the capacity to form cell types of seemingly unrelated tissues and organs. It’s a kind of differentiation that goes across tissue or organ barriers and so is referred to as transdifferentiation.

In your studies, what has been your most interesting finding?

My own particular findings, made in collaboration with Dr. Piero Anversa and his staff at New York Medical College in Valhalla, NY, have been directed at the capacity of adult mouse bone marrow stem cells to differentiate into cells of the heart, and what is more, to repair damaged heart tissue. To date, this work has been exclusively in mice. The original paper was published in Nature in April 2001.

How difficult is it to extract these adult stem cells?

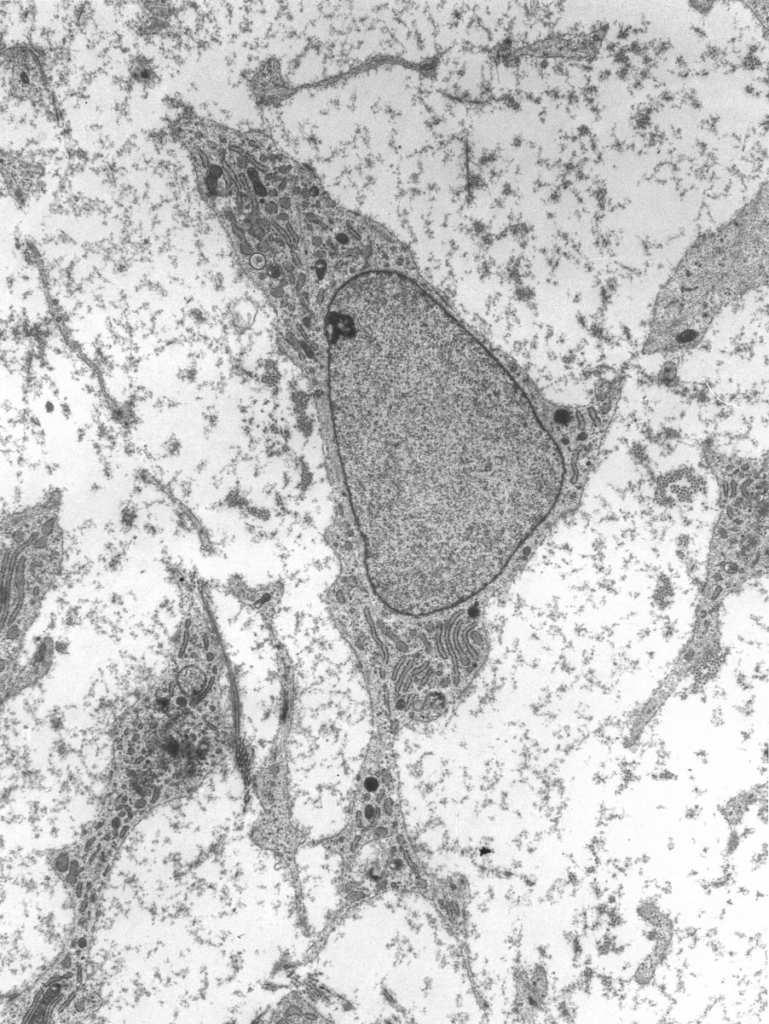

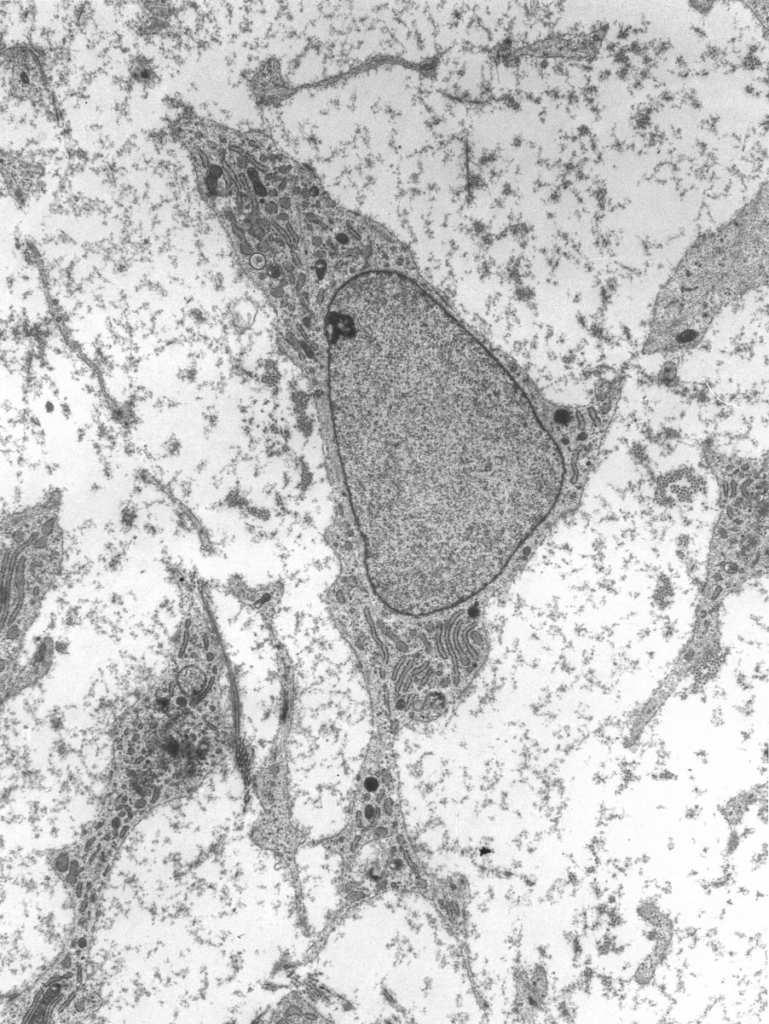

Although the bones are small, it’s not difficult at all to harvest adult mouse bone marrow. It takes some effort and experience to purify the stem cells that we are referring to because these cells are present in a ratio of one per 10,000 bone marrow cells. You can see that they are an extremely rare population of cells. We and other researchers have found a way to enrich them using surface antigens or surface protein markers that are recognized by monoclonal antibodies and on the basis of that labeling with monoclonal antibodies, we’re able to enrich these cells tremendously using the power of flow cytometry.

What is this instrument used for?

In combination with appropriate surface protein markers, a flow cytometer gives us the capacity to eliminate the cells that are not recognized as stem cells. These cells are highly concentrated or purified and they have a tremendous potential for expansion and differentiation into mature blood cells after transplantation into recipients. As few as 50 of these cells can repopulate the entire hematopoietic system of an animal. That is how all of this work began.

So this research has been going on for a while?

The study of stem cells is something that has been interesting to people who work in hematology, going back as long as anyone can remember. It has always been realized there was an ultimate cell that was referred to as a stem cell but virtually nothing was known of its characteristics—either its morphology or its functions—until the last twenty to thirty years. So that’s not new; what is really new is the fact that the stem cells which have been studied and utilized in bone marrow transplantation for patients with blood diseases for years have been shown to have this newly discovered characteristic of producing cells of different organs.

Do these stem cells have therapeutic uses?

These bone marrow stem cells definitely have therapeutic uses. They’re used extensively in every hospital where bone marrow transplantation occurs.

What about the therapeutic potential based on your work with cardiac tissue?

We deliberately injure the heart of adult mice and then, using these adult bone marrow stem cells, we repair the injury. Our finding is that these adult bone marrow stem cells had the capacity to regenerate new tissue—both muscle tissue and blood vessels. As a result of the newly repaired areas of the injured heart, those hearts showed an improved function. They had the capability of functioning better than the controls that were not given bone marrow stem cells.

Have you tried the repair of other deliberately injured organs?

We have not to date done anything like that, although the damage that we can induce in the heart can also be induced in other organs such as the kidneys or the brain. What we did essentially was to mimic a heart attack in these adult mice. So it’s a condition very similar to what we see in human patients. This work is not yet at the stage of pre-clinical trial.

However, it is an early, promising and exciting study. We are pursuing additional work along these lines but we have not reached the point of saying that we can be engaged in pre-clinical trials and certainly we don’t feel that the observations that we have published justify going to clinical trials on human beings at this time.

What happens to the control mice not given the stem cells?

If left untouched, in the region where the blood flow was blocked or deprived, healing would soon begin in the form of a scar. Without intervention of any sort, the healthy cells die, the blood vessels are destroyed and the entire tissue is replaced by scar tissue similar to when you cut your skin. If we intervene at an early time following the induction of a heart attack in these mice, then we can prevent the scar tissue formation. What’s even more important is that the cells that we inject into the heart have the capacity to regenerate new tissue where that damaged tissue occurred.

Did you observe any rejection in your studies?

Rejection of course is always a possibility but in our particular study, the mice are inbred strains that share the same immune markers. They have the same histocompatibility antigens. When we harvest their bone marrow, these mice do not survive; we remove bone marrow from a small number of mice, purify the stem cells and inject those cells into a compatible mouse that has the induced myocardial infarct or heart attack. In our model, there is no issue of incompatibility because these are inbred strains. If we were to go on to a large animal model like dogs or monkeys, there always is the possibility of an immune reaction to the transplanted cells.

How were the stem cells delivered to the damaged hearts?

These stem cells are delivered directly into the beating hearts of these mice—not into the cavity of the heart—but into the wall where the damage occurred. We exteriorize the heart through the chest wall and while it’s beating, we inject the stem cells directly into the beating heart and then they migrate from the site of injection into the site of injury. These cells then receive some signals which we have not yet been able to identify that induces them to multiply and also to differentiate into muscle cells of the heart.

Could you say that there was a cure in this case?

Yes, you could definitely say that. It’s not 100% yet in our first study but the improvement in our study was 35% over the level of heart function in those hearts that were damaged but not treated with these bone marrow stem cells. So there was a better recovery in those treated hearts; thus it’s a partial cure.

Have you used embryonic mouse stem cells to treat these damaged hearts?

We have not done any work with mouse embryonic stem cells. There are others who have tried to use mouse fetal and mouse embryonic stem cells in heart repair. Although they report a degree of success, no one working with either embryonic, fetal, or adult stem cells, to my knowledge, has ever repaired the injured heart tissue to the degree that we have succeeded with adult bone marrow stem cells.

So adult stem cells seem to work better in this case?

For the time being, based on the experiments that have been done thus far, the most successful approach has been with adult bone marrow stem cells.

What are the future directions for your research?

With the mouse model, we intend to extend our observations to four to six months which is a large portion of an adult mouse life span. Since mice live between one and a half to two years, extending the time frame should hopefully show us a better rate of success. Then we will extend these studies to larger animal models.

I think one of the important things that we must learn if we’re to advance this field significantly is what controls transdifferentiation in these bone marrow stem cells. What signals are necessary to induce a response in bone marrow stem cells to become heart muscle cells?

When we know what these signals are—and we do not to date—whether it’s in regard to bone marrow stem cells or mouse fetal or mouse embryonic stem cells, then I think we will have a lot more information about how these cells accomplish what they do. That in turn will allow us to explore what today seems to be an unlimited capacity to generate cells of a different type than we previously thought possible.

Also read: Tapping into the Potential of Regenerative Stem Cells