From Tools to Meta Humans: Talking to AI

In the final installment of this year’s distinguished lecture series hosted by The New York Academy of Sciences’ Anthropology Section, an expert panel discussed the intersection of anthropology, technology, and ethics.

Published May 2, 2025

By Brooke Elliott

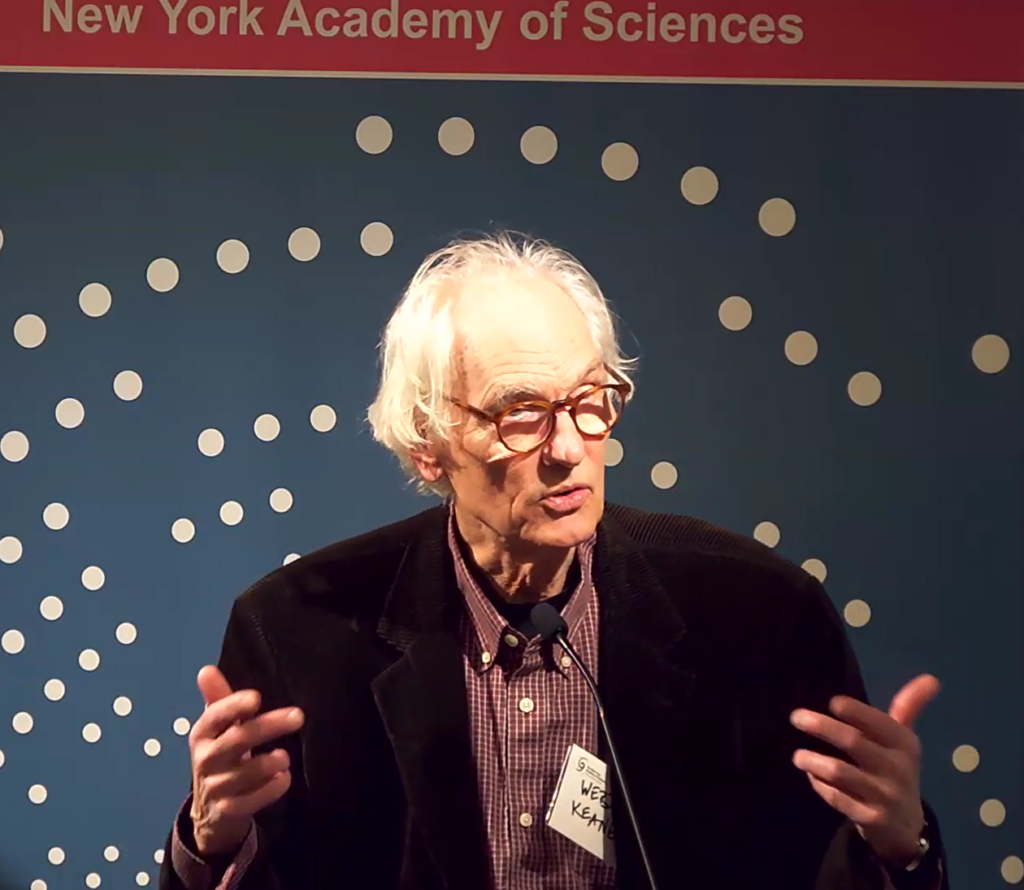

Keynote speaker Webb Keane, PhD, the George Herbert Mead Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the University of Michigan and a leading voice in semiotics, media, and ethics, centered his April 7th talk around his new book Animals, Robots, Gods: Adventures in the Moral Imagination. The book moves beyond human communities and explores the relational ethics that arise from human interaction with non-humans and near-humans, including artificial intelligence.

Prof. Keane opened his presentation by posing the provocative question: What defines a human?

Traditionally, it has been humankind’s capacity for language, tool-making abilities, and moral reasoning. But with the rise of generative AI and large language models, all three are under pressure, according to Prof. Keane.

AI as a Metahuman

Generative AI now challenges humankind’s unique position as language users, introducing tools that seem to “escape the grasp” of their creators. These AI systems don’t merely reproduce human intelligence, they imitate its outputs.

Prof. Keane defines a “metahuman” as “someone or something with superior powers, but lacking a body or particular social location.” These are beings that humans have always interacted with, such as gods, spirits, and, now, robots and androids. These entities possess knowledge, power, and moral authority beyond the human.

Religious communities have taken to AI in surprisingly enthusiastic ways, Prof. Keane pointed out. Tools like Gita GPT, designed to simulate answers from Krishna, a major deity in Hinduism, are used for moral and spiritual guidance. AI’s “oracular affordances,” as Prof. Keane called them, allow it to function like ancient divinatory tools; they can elicit meaning, trust, and belief.

“AI reflects our fears because it is built from our language, our stories, our digital footprints,” said Prof. Keane.

The meanings we get from interactions with AI are the product of collaboration between the person and the device, just as divination, spiritual possession, and speaking in tongues once captivated our imaginations.

Omri Elisha’s Response

Responding to Prof. Keane, Omri Elisha, PhD, associate professor of anthropology at Queens College and the City University of New York Graduate Center, drew parallels with his own work on astrology. Prof. Elisha emphasized that technologies like AI and astrology translate abstract forces into moral guidance. Through symbolic systems, users interact with planetary or digital forces as if they have agency.

Prof. Elisha posed the critical question: “How is it that certain technologies and certain symbiotic mediations come to be authorized to speak for transcendental sources infinitely far from the here and now?”

He also addressed society’s growing reliance on crowdsourced truth. Platforms like Google and Reddit are worshipped for their convenience, immediacy, and trust, even by those who claim to be skeptical. Generations raised on the internet have come to accept the “wisdom of large numbers,” as Prof. Keane calls it

To further support this point, Prof. Elisha cited the viral meme, “A world where AI paints and writes poems while humans perform menial, backbreaking work wasn’t the future I imagined.”

In an age of corporate personhood and surveillance capitalism, many allow branded algorithms to make decisions once left to human discretion, including immigration status, medical diagnoses, and even music recommendations. As Prof. Keane notes, “We should be scrupulous about the would-be gods who lurk behind our devices.”

Danilyn Rutherford’s Call for a Global Perspective

Danilyn Rutherford, PhD, President of the Winter Grant Foundation and activist with A Thousand Currents, praised Prof. Keane’s commitment to ethical nuance. Still, she challenged the limits of cultural relativism. While different societies may live by different moral codes, Dr. Rutherford argued that there’s a deeper universality in our capacity for meaning-making, even across radically different contexts.

“The point, [Keane] argues, is not simply that different ponds nurture different frogs, they nurture different relationships among critters swimming in the same puddle,” said Dr. Rutherford.

Fear, Faith, and the Future of Human Meaning

All three speakers converged on a core insight: that our interactions with AI tell us more about ourselves than they do about the technology. Humans are beings who construct meaning collaboratively, introducing non-humans with agency, because of our innate ability to see intentions in others.

As Prof. Keane emphasized, the real question is not whether AI is sentient, but why we respond to it as if it were. He questioned what does that reveal about our values, our anxieties, and our longing for guidance as we continue toward an era with even greater interaction between humans and AI.

As the 2024–25 lecture series concludes, the Anthropology Section is already looking to the future. A graduate student gathering at the Margaret Mead Film Festival, which takes place May 2-4 at the American Museum of Natural History, will provide a final chance to connect this spring. This fall, the Anthropology Section will return with a new theme and speaker lineup, as well as a continued commitment to bridging anthropological insight and public dialogue.

Learn more about offerings from The New York Academy of Sciences’ Anthropology Section.