Building Bridges in the Humanities and Sciences

To understand how Nicholas B. Dirks is leading The New York Academy of Sciences, it may be helpful to learn more about three of his passions: the liberal arts, interdisciplinary studies, and southern India.

Nicholas Dirks is a historian, anthropologist and accomplished university administrator. To understand the arc of his career—and how he will lead The New York Academy of Sciences—it may be helpful to understand three of his passions: the liberal arts, interdisciplinary studies, and southern India. The southern India story begins when Dirks was quite young.

A Magical Year

Dirks’ father, then a professor at the Yale Divinity School, took his family to South India in 1963, when Nicholas was a young boy. J. Edward Dirks had received a Fulbright grant to teach at a college in Chennai, then known as Madras, and the experience came at an impressionable time for his young son.

“I read a lot as a kid,” Dirks recalled in a recent interview. “And here all of a sudden, it was almost as if a book opened up, and the pages that I was reading felt alive and real in a way that nothing really had quite done before.”

This is the way Dirks put it in an introduction to a collection of his essays:

“I had no way of knowing I was going to miss out on the emergence of the Beatles, though I had the usual concerns about leaving my junior high school friends and the eighth grade. But I was excited by the prospect of adventure… and, as it turned out, the year was magical. The college campus did have acres of jungle, and there were peacocks, cobras, and leopard cats, much to my mother’s horror. I attended school in a khaki uniform; studied the south Indian drum, the mridangam… and learned how to negotiate the extremely efficient bus system of the city of Madras.”

Dirks would go back to India many times throughout his life, and he anchored much of his scholarship there.

Wesleyan University

Back in the U.S. with his family after a year, Dirks was influenced by visiting speakers at church services at Yale, and by the University’s chaplain, William Sloan Coffin, a prominent supporter of the Civil Rights movement and critic of the war in Vietnam. In high school, Dirks devoured books on philosophy and the social sciences assigned by an influential teacher, who also recommended that Dirks apply to Wesleyan University. Wesleyan famously was open to diverse interests and liberal studies, and Dirks was sold when he discovered Wesleyan had a group of South Indian musicians and a program in ethnomusicology; he could study mridangam —the south Indian drum—there.

Dirks arrived at Wesleyan’s campus in Middletown, CT in the fall of 1968. He could not help but be influenced by all the unrest around the war in Vietnam, which was at its peak:

“Initially I thought I was going to major in philosophy, because I was interested in ideas. I think a combination of my experience in India and the war in Vietnam led me increasingly, however, to think that I needed to study Asia…. It was important to me personally, and it was also important to all of us politically. And I felt I needed to understand not so much Asia’s philosophy and religion, but instead, its history and politics and economics.”

Dirks majored in Asian and African Studies. For a senior thesis, he traveled back to the state of Tamil Nadu, and learned to speak Tamil in the city of Madurai. It was a difficult six months, amid crowds and poverty, but Dirks was writing about Gandhi and the anti-caste movement in southern India, and became very interested in connections between all this and the Civil Rights movement back home. Dirks decided to study the history of southern India in graduate school, and he applied to the University of Chicago.

The University of Chicago

When Dirks arrived in Chicago in 1972, he came to a university that had built a major South Asian studies program, with faculty from across the full range of the humanities and social sciences. Dirks took good advantage of the opportunity: “You could do just about anything in this kind of area studies program. You could study ideas, literature, social change, economics, or the role of science in society. Area studies drew on multiple disciplines and tapped into some of the most central concerns of top thinkers at the university.”

The University of Chicago was also an important center for cultural anthropology, and Dirks found anthropology helped him in “trying to come to grips with how to study India from the point of view of an American by birth and upbringing.” Dirks was also drawn to the types of questions anthropologists were asking, especially about cultural relativism:

“It seemed to me that anthropology was taking on some of the big questions of the time…. What is the nature of cultural difference? Are fundamental beliefs—in terms of judgement, in terms of fundamental common sense and orientation toward the world—determined by culture? Or are they determined by biology? Are there universal laws that allow you to understand “difference” in all of its complexity? These were not issues at the time that historians were thinking about a great deal. But it was very much part of the milieu of the anthropology group there.”

Dirks continued: “The interdisciplinary mix of these first years of professional scholarship not only built on the interdisciplinary base of my undergraduate days but also launched a lifelong conversation in my own work, teaching, and thought about the relationships among history, anthropology, and critical theory.”

For his dissertation topic, Dirks turned to the social, political, and economic relationships within the “little kingdoms” of southern India, regions of varying size ruled by local chiefs dating back to the thirteenth century. Dirks used historical approaches, with archival research in London, New Delhi, and in the small city of Pudukkottai. Dirks then spent a year in Pudukkottai, the former capital of one of the “little kingdoms,” doing the kind of field study that is at the heart of cultural anthropology.

As he was writing his dissertation, Dirks gained teaching experience at a small, nearby college, and then, at 27, headed west to Pasadena when he was offered his first fulltime job.

California Institute of Technology

In 1978, Dirks began what would be eight years at Caltech. He taught Introduction to Asian Civilization, a distribution course. He made another trip to India to research his first book, The Hollow Crown, a study of Pudukkottai using approaches from both ethnography and history. And Dirks also got to know accomplished scholars in the hard sciences.

“They had this wonderful, storied, faculty club called The Athenaeum,” Dirks recalled. “And they had these round tables that facilitated random seating. The idea was that you would go and meet faculty outside of your department or division. And it turned out that a number of the senior scientists were the ones most interested in talking to a young faculty member who had just arrived to teach courses in humanities and the social sciences.”

To Dirks, these seemed like Renaissance figures, interested in everything. The group included Max Delbrück, a Nobel Laureate who was a pioneer in the study of molecular genetics. He got to know Richard Feynman, the colorful Nobel Laureate in theoretical physics. “And I got to know Murray Gell-Mann, the inventor of the quark, because he had a great interest in Indian philosophy,” Dirks recalled. “And you know, it was world opening, eye opening in every way, to be there with somebody who invented the quark who wanted to ask you about some esoteric eleventh century Indian philosopher.”

Dirks said he started seeing connections between the hard sciences and his own fields of study. “You know, until I went to Caltech, I thought that in academia, one went into science and engineering, or you went into humanities and social science,” Dirks said. “And so for me, being at Caltech was, in effect, an opportunity to live across the two cultures.”

The conversations at the round tables, Dirks said, mirrored in some ways what he experienced in India. The hard sciences were strange and familiar at the same time. Strange because they were built on foundations of knowledge he never studied. “But they were also familiar because some of the core questions that people were asking were things I was interested in as well,” Dirks continued, adding:

“And anthropology was an interesting point of connection, because you began with discussions, for example, concerning the debate between nature and culture, of relevance to science as well as social science. But you were also attuned to debates about different world views. And it was an easy move from there to ask questions about the meaning of the universe, and then, say, to cosmology. Astrophysicists were naturally drawn to questions that bridged science and philosophy. And, as we talked about a wide range of subjects, we all realized that even the ways we use metaphors to understand the world are similar, whether you’re thinking in terms of history or whether you’re thinking in terms of natural laws.”

The University of Michigan

From Caltech, Dirks moved to the University of Michigan, where he would have graduate students for the first time. He assumed a joint appointment in the history and anthropology departments and, with a colleague, built an interdepartmental PhD program in both disciplines. It was a good time to start a program formalizing a relationship between the two fields.

Many historians at the time were de-emphasizing politics and intellectual history, focusing instead on social and cultural phenomena, perspectives that aligned with touchpoints in cultural anthropology. And scholars in anthropology were placing more emphasis on political and economic forces, the traditional frameworks of historical research.

Columbia University

The historical turn in anthropology, in addition to Dirks’ work in founding the interdepartmental PhD program at Michigan, led to an offer in 1997 to chair the oldest department of anthropology in the country, at Columbia University.

Dirks broadened the department, recruiting new faculty from Asia and Africa, and supported research in colonial and postcolonial studies, increasingly popular areas of focus at the time. And in 2001, Dirks published his second book, Castes of Mind, in which he demonstrated the extent to which the caste system had changed under British colonial rule, and was changing still as it became the social base of many postcolonial political movements. The book won several major awards and is still widely taught in graduate curricula in the U.S. and India.

Earlier, at the University of Michigan, Dirks started honing administrative skills, having discovered that bridging the anthropology and history departments would require that he drive institutional change. In 2004, at Columbia, Dirks stepped into administration full time, giving him opportunities to promote interdisciplinary study across all of the liberal arts and sciences. He became Vice President (later, Executive Vice President) of the Arts and Sciences and Dean of the Faculty.

In his new roles at Columbia, Dirks oversaw 6 schools, 29 departments, and a number of special programs and labs. Dirks channeled his learnings from Caltech and made special efforts to reach out to the chairs of the science departments. He committed to renovating science buildings and laboratories, and commenced planning for a new science building. Even there, Dirks says he “built on his interdisciplinary interests” by creating a building plan that located the laboratories of scientists from different disciplines adjacent to each other “so that they would have to interact.”

Of his new role at Columbia, Dirks said: “That’s where I really began to understand not just the intellectual interests of scientists, but, also the needs that they have, what it takes to allow great research to take place in the natural and physical sciences.”

Dirks also stepped up fundraising at Columbia, and in 2008, he helped the university establish a Global Center in Mumbai.

University of California, Berkeley

In 2013, Dirks moved back to California, to become the tenth chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley. As with Columbia, he would have responsibilities across all the arts and sciences, including engineering, law, and business, but now at a public research university with a $2.4 billion budget.

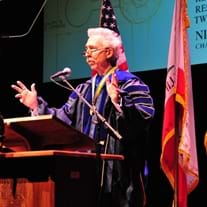

At his inauguration ceremony, Dirks, in charge of a world-renowned university dependent on public funding, said he wanted to “re-assert the value of research and higher education for the public good.” And reflecting his long interest in interdisciplinary approaches to the humanities and sciences, he promised leadership to build bridges—rather than barriers—in academia:

“I resist the stark divide between teaching and research, between general and professional education, between basic and applied research, between the arts and the sciences, between private interests and public good, between our local obligations and our global ambitions, between disciplinary specialization and multidisciplinary collaboration, between our commitment to diversity and to academic excellence, between the goals of a college and the aspirations of a university.”

Dirks’ accomplishments as chancellor include significant improvements in undergraduate facilities and programs, such as a new initiative in data science and data analytics that serves students across all majors.

Dirks also strengthened alumni relations and reorganized the fundraising system. This led to large increases in donations—almost $500 million in 2016 alone—which helped offset ongoing reductions in public funding.

Dirks built connections to institutions around the world, establishing partnerships with Cambridge University and the National University of Singapore. Dirks also helped develop a joint research and educational partnership with Tsinghua University in the Chinese city of Shenzhen. And, with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Dirks partnered with Tsinghua University in Beijing on a joint research center focusing on energy and climate change.

In the US, Dirks invested in research collaborations in neuroscience and genomics, and strengthened ties with the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) medical school. Dirks also guided Berkeley’s participation in the $600 million Chan Zuckerberg BioHub, a partnership with Stanford and UCSF, to develop technologies to improve healthcare.

The New York Academy of Sciences

Dirks’ most recent scholarship has been on the history and future of the American university. After being recruited to lead The New York Academy of Sciences, Dirks noted that, “As I see it, The New York Academy of Sciences is a very fitting culmination to all the things that I’ve been doing in my career…. it promotes scientific research, it aims to connect scientific expertise with policy discussions more broadly, and it is committed to science education. I intend to build on its long and venerable history of connecting science with the core issues and challenges of our time.”

Dirks returned to New York with plans to marshal the resources of the Academy, which he describes as a “learned society open to everybody,” to help address the most pressing questions and problems facing the world: Instead, he accepted the position just before the pandemic, which brought the entire world’s attention to the role of science in combating disease. In his first few months at the helm, he launched a series of webinars to address scientific questions having to do with the nature of the virus, the development of vaccines and other therapies, and the broader impact of the pandemic, including the rise of skepticism about science itself. And yet, as he wrote at the time:

“Almost every major issue we’re confronting today is of central concern to the Academy: whether it’s climate change, the pandemic or infectious disease more broadly, the relationship of inequality to health outcomes, or the whole set of questions that arise with technology— for example, machine learning, artificial intelligence and robotics as they promise new kinds of scientific solutions while at the same time threatening our traditional understandings of the difference between machines and humans. In my view, the Academy can and should play a critical role in enabling our city, our nation, and the globe to take on these issues with the requisite commitment to scientific knowledge, perspective, education, and advocacy.”

The world has changed a great deal since Dirks was a junior high school student in Madras. “When I first went to India I was fascinated by cultural difference,” Dirks said. “But gradually I became more struck by our human commonality — and by the forces of modernity that link us all closer and closer together.” That deep understanding of commonality, coupled with his long history of building bridges not just across cultures but across the disciplines of the arts and the sciences, will help Nicholas Dirks effectively lead The New York Academy of Sciences as it enters its third century.

Nicholas Dirks lives in New York City and Berkeley, with his wife, Janaki Bakhle, a Professor of History at UC Berkeley and author of Savarkar: The Making of Hindutva. Dirks himself has recently published the quasi autobiographical book, City of Intellect: The Uses and Abuses of the University.

Photos by: Keegan Houser