Finding New, Sustainable Uses for Food Waste

According to the EPA, organic waste is the largest component of landfills. Researchers are working with businesses to develop innovative ways to reduce this problem.

Published May 1, 2020

By Charles Ward

Academy Contributor

Bertha Jimenez wasn’t a beer drinker when she came across spent grain for the first time.

A mechanical engineer by training and now the CEO of Rise Products, Jimenez recounted her tour of Brooklyn Brewery, a craft beer brewery located in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, N.Y.

“I’m interested in how waste from one industrial activity is usable in another,” she said. “So as we walked around the plant, I wanted to know what happened to the source grains after the beer was made.”

Within a year, Jimenez founded Rise, a start-up that converts spent grain into specialty flours sold directly to bakeries. Rise developed a proprietary conversion process, slogged through prototypes and proof-of-concepts, and learned about food safety standards. She built a regional B2B customer base, secured grants, raised private capital, and signed a Service Provider Agreement with Anheuser-Busch.

“People like to feel like they’re doing something sustainable, something good,” she said. “But at the end of the day we don’t eat ideology, you know?”

The Challenge of Food Waste

Jimenez is just one example of the way the scientific community has deeply engaged with the challenge of food waste: as entrepreneurs, researchers, academics, regulatory policy specialists, or NGO advisors.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates 31 percent of food produced in the U.S. is loss, with an annual economic value of $161.6 billion. Globally, the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) estimates 1.3 billion tons of food are lost every year in agricultural production, post-harvest storage, processing and distribution, and consumption.

New policy priorities reflect an emerging consensus among food production experts that these are unacceptable numbers for a global food system already stressed by a growing population and climate change. Goal number 12 of the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Agenda is to “ensure sustainable food consumption and production patterns.” Targets include cutting per-capita global food waste in half at the retail and consumer level by 2030, and reducing food loss from production and supply chains. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and USDA share a similar goal, to cut food loss and waste in half, also by 2030.

Multiple Missions

Photo credit: Rise Products, Inc

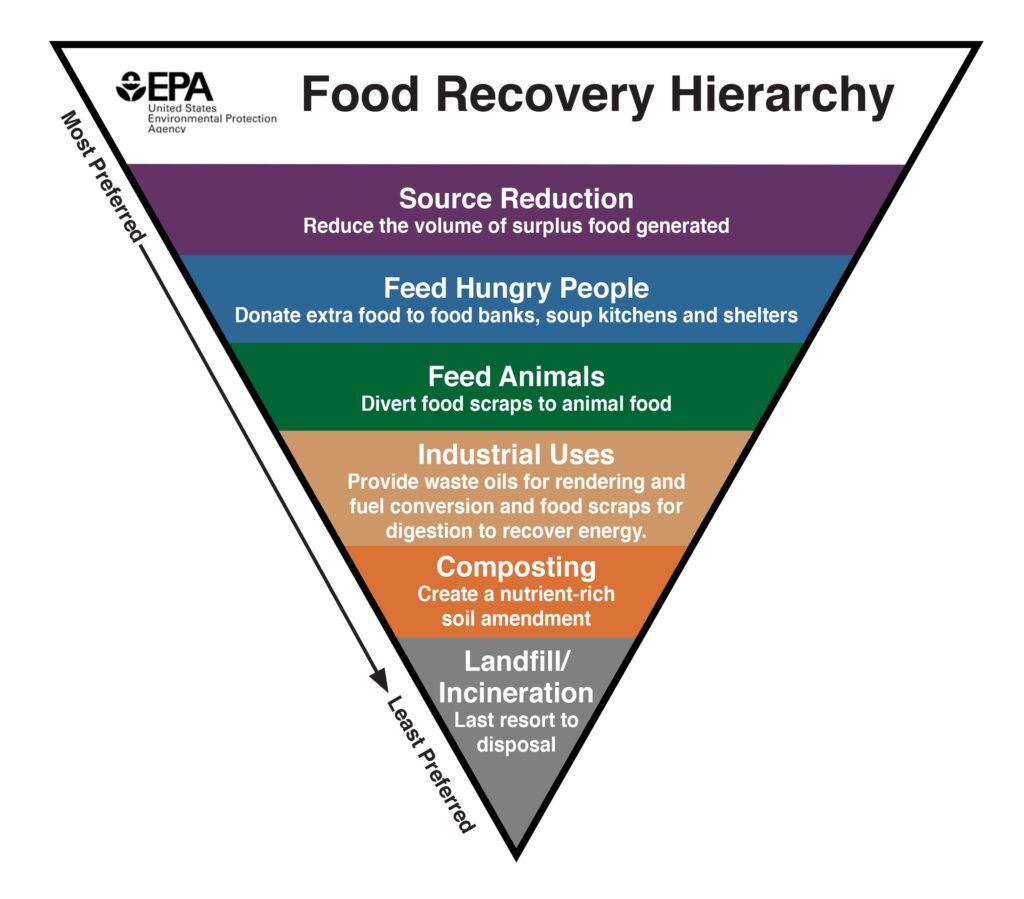

For Elise Golan, Ph.D., Director of Sustainable Development for the USDA, food waste is a resource efficiency challenge. She works closely with colleagues at the EPA, and references the EPA’s well-known “Food Recovery Hierarchy” inverted pyramid, which visually represents the flow of food from “upstream” agriculture source to “downstream” table, and the parallel opportunities to conserve resources at every stage of the chain.

“We look at reasons for waste, and ask if there are cost-effective ways to reduce it,” she explained. “If we’re producing food that is wasted, [by reducing it] we can conserve the land, water, chemical- and non-chemical inputs that go into that food.”

The USDA’s more active food recovery interventions, Golan notes, are prompted by opportunities to create efficiency all along the value chain. As one relatively upstream example, she points to a pilot collaboration between the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service and The Wonderful Company, a California-based producer of pistachios. The project has the potential to turn mountains of discarded pistachio shells into “carbon black” for use in plastics as an alternative to petroleum-based compounds.

“They’ve done it in a very cost-effective, energy saving way,” said Golan. “It is really is a big win for the environment.”

Food Waste as an Economic Catalyst

If the USDA is working on food waste from the top down, Juan Guzman, Ph.D., is working from the bottom up. Guzman is the head of Capro X, a Cornell University spin-off that uses bioconversion technology to turn the acid whey left over from Greek yogurt production into specialty chemicals. In commercial terms, Capro X is what is classically called a “category creator.”

Guzman thinks of himself first as an entrepreneur, and speaks in terms of business cases: return-on-investments, stakeholder buy-in, and use of science-based innovation to create entirely new markets. When he started Capro X, the commercial imperatives were self-evident: New York yogurt manufacturers needed cheaper ways to get rid of large quantities of acid whey, which they had to truck long-distance for waste-water treatment.

Alternative Sourcing for Industrial Products

At the same time, dairy farmers, generally, were under pressure to develop new products as milk consumption declined. And global agribusiness giants, like Nestlé, Archer Daniels Midland and Cargill, are always seeking alternative sourcing for industrial products, like commercially farmed palm oil, which Capro X intends to produce.

“I just see so much opportunity in using biology to extract value out of things that people are willing to pay to get rid of,” said Guzman, pointing to the historic precedent of ethanol, which made the planting of corn on previously surplus or marginal farm acreage a hugely viable commercial proposition. “For yogurt manufacturers, we’re talking about waste streams measured in the millions of pounds, with one facility alone generating a quarter of a million pounds a day of pure lactose sugar for conversion,” Guzman continued. “And there are hundreds of plants in the U.S.“

For the market to scale, investor interests will have to see the opportunity, and put in capital. In the meantime, Guzman is building his new market one customer at a time. Capro X’s value proposition includes installing the acid whey treatment equipment at dairy farms. He keeps the specialty products, and farmers are spared the expense of trucking away waste. Guzman said he has learned that farmers like the idea of sustainable waste practices, but they are not necessarily willing to pay a price premium for them.

Identify, Measure, Attempt to Solve

Mary Muth, Ph.D., is an agricultural economist who serves as the Director of Food, Nutrition, and Obesity Policy Research at RTI, a not-for-profit organization dedicated to using science for good. Muth has conducted food waste research from every angle: malnutrition, resource efficiency, economic impact, and ethical imperative. She believes that scientific interest in the problem of food-waste is still cresting.

She also points out that that commercial application of food-waste research is still largely voluntary. Some companies see it as a reputation management opportunity, a way to promote corporate social responsibility. A few others have developed niche products. Seismic economic incentives for waste-aware practice don’t yet exist.

“It will probably take some significant disruption in the food supply to bring around big scale change,” Muth said.

Christine Beling, a project engineer and New England regional director of Brownfields and Sustainable Materials Management at the EPA, is as good a witness as any to what seems to be an incremental and steady advance towards reduced food waste. The EPA prefers composting as an alternative to landfills for food waste, and Beling says that a sign of progress is landfill bans of organic waste by four of the six New England states in her region. She notes that in 2015, the EPA calculated that just 5.3 percent of 39 million tons of food waste was diverted for composting; two years later, the figure was 6.3 percent.

“That’s a relatively big jump,” she observed. “If you go back to the late ’90s or early 2000s, it was one percent. I think you can see the trend.”

Entering the Mainstream Conversation

Beling points to a variety of legislative, academic, and NGO attention on food waste and recovery. In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act, which provides liability protections to nonprofit organizations when they donate food. In 2019, Harvard University launched its Food Law & Policy Clinic, which trains students in the use of legal and policy tools to address food system issues.

Beling also calls attention to the birth of new NGOs like ReFed, founded in 2015, to bring data- and economics-driven tools to help solve food waste problems. And in 2016, the Ad Council and the Natural Resources Defense Council co-sponsored the “Save the Food” national public service campaign.

“The emphasis may be different depending on what part of the world you’re in, but overall there’s a whole shift,” said Beling. “Ten years ago, people didn’t want to deal with food waste. Now, everybody’s dealing with it because it’s in the mainstream conversation.”

Read more: