From research in the biophysics of RNA to advances in cancer immunotherapy and vaccine antibodies.

Published October 1, 2017

By Kari Fischer, PhD

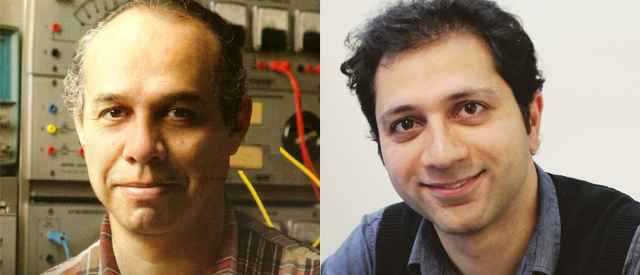

Jeffrey V. Ravetch, MD, PhD, Theresa and Eugene M. Lang Professor and head of the Leonard Wagner Laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Immunology at The Rockefeller University, received the 2017 Ross Prize in Molecular Medicine — established in conjunction with the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research and Molecular Medicine — for his discovery of how antibodies generate a wide range of immune responses: through Fc receptors.

The path to this accolade was a hard won fight. Ravetch’s work challenged a dogma of immunology, and consequently he spent his first 20 years as an independent investigator in relative isolation. When asked how he would encourage other researchers to drive through such a period, his response was emblematic of his career.

“I think the point of science is that you never stop learning. You have to continually push yourself to be uncomfortable in a new field, and potentially get up there and say something that’s wrong,” Ravetch says.

Raised in the Sputnik Age, Inspired by Scientists

Raised in the age of Sputnik, a young Ravetch elected scientists instead of sportsman as his heroes — absorbing the biographies of Louis Pasteur and Albert Einstein. Recounting his first experiments in his high school basement, without any guidance, Ravetch laughed, “It’s remarkable how naïve I was.” He studied the embryonic development of zebrafish, using a homemade frame to collect the embryos and a borrowed microscope.

Transitioning into more formative research, Ravetch delved into the biophysics of RNA folding as an undergraduate. He subsequently earned an MD so he could apply his findings to human disease, a PhD in bacterial genetics and a postdoc employing molecular biology to study antibody recombination. Ravetch had no one love in science, except for science itself.

When first pursuing antibody receptors that may mediate inflammatory responses, he encountered either indifference or bewilderment as the mechanism for this process already existed: through the complement system. But Ravetch had the benefit of not yet being an immunologist — he lacked the tunnel vision that can form when studying one field — and instead was driven by a basic interest in the structure and function of Fc receptors.

Groundbreaking Work in the Role of Antibodies in Vaccine Development

His group eventually demonstrated that the Fc region of antibodies can either induce or suppress an immune response by binding to the activating or inhibitory versions of Fc receptors on immune cells — without complement. This was groundbreaking, and opened many questions on how antibodies can fine tune immune activation or suppression.

Ravetch found one answer through a bit of serendipity: he was invited to the right conference. Knowing little about intravenous gamma globulin (IVIG) therapy, he flew to California to attend a clinical meeting on the topic. IVIG is the administration of antibodies isolated from donated blood, and is given as an anti-inflammatory.

How IVIG worked was unknown, and Ravetch heard an abundance of theories at the conference. None were satisfying, and Ravetch had a new question to chase.

He returned to the lab, and found that IVIG’s therapeutic effects occurred through the inhibitory Fc receptor. Moreover, the antibodies’ ability to induce an inhibitory response, and dampen inflammation, resulted from the presence of specific carbohydrates attached to their Fc region. The presence and structure of those carbohydrates dictates the type of Fc receptor with which they can bind. Reigniting his undergraduate training on intricate molecular relationships, Ravetch went back to “school.”

“Nothing prepared us for this kind of interaction, and it was fascinating. It was one of those wonderful Christmas vacations where, for two weeks, I just sat and read up on carbohydrates,” he says.

Extending into Cancer Immunotherapy, Improved Vaccine Design

Beyond scholarly pursuits, these discoveries influence therapy. Ravetch’s findings on Fc receptors had not yet gained traction at the advent of therapeutic antibodies, and pharmaceutical companies focused on the antigen-binding variable region, not the Fc.

This carried into the pioneering field of cancer immunotherapy, where many promising agents were successful in mice, but then failed in the clinic. There, Ravetch cites a lack of attention to the Fc, and he now collaborates with companies to share his expertise and develop better therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of cancer, inflammation and infectious diseases.

Lately, Ravetch is branching into a new area with vaccines, exploring how antibodies offer protection upon vaccination, and how that knowledge could improve vaccine design — perhaps yielding a universal flu vaccine. Beyond that, Ravetch does not have a plan, but this is true to his style.

“I don’t really know what’s going to happen in the next weeks or months. There’s a certain expectation based on what you’re doing, but if you don’t see unexpected observations, the fun is gone,” he says. “I’m looking forward to the unknowns.”

Read more about the Ross Prize and past awardees: