The Inception of The Academy

The New York Academy of Sciences stands as a venerable institution with a rich and storied history that spans over two centuries. Established in 1817, the Academy has consistently been at the forefront of scientific exploration, education and the formulation of policies that shape our world. This enduring legacy continues to influence the course of science and society into our third century.

The Academy’s first home: On January 29, 1817, Academy founder Samuel Latham Mitchill convened the first meeting at the College of Physicians & Surgeons in lower Manhattan.

1800-1850

1817

At a time when New York City north of Canal Street was fields and forests, when the only academic route to a scientific education was medical school, and when learned societies were often reserved for men of wealth, a small group of young naturalists banded together to create the Lyceum of Natural History, founded on egalitarian principles. On January 29, 1817, Academy founder Samuel Latham Mitchill convened the first meeting at the College of Physicians & Surgeons in lower Manhattan. A U.S. Senator from New York, Mitchill was a professor of chemistry and natural history and was also responsible for establishing the first medical journal in the US.

That same year, an upstate farmer unearthed the jaw of a mammoth on his property—a spectacular first at a time when fossils were rarely encountered. He contacted Mitchill, who organized an expedition under Lyceum auspices to investigate further.

1824

From the Lyceum’s earliest years, members could keep abreast of science around the world through it sever-expanding library. In 1824 the Lyceum launched its journal, Annals of the Lyceum of Natural History of New York. By exchanging Annals for the publications of scientific organizations worldwide, the Lyceum built its collections. Known today as Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, it is one of the oldest continuously published science journals in the United States.

1829

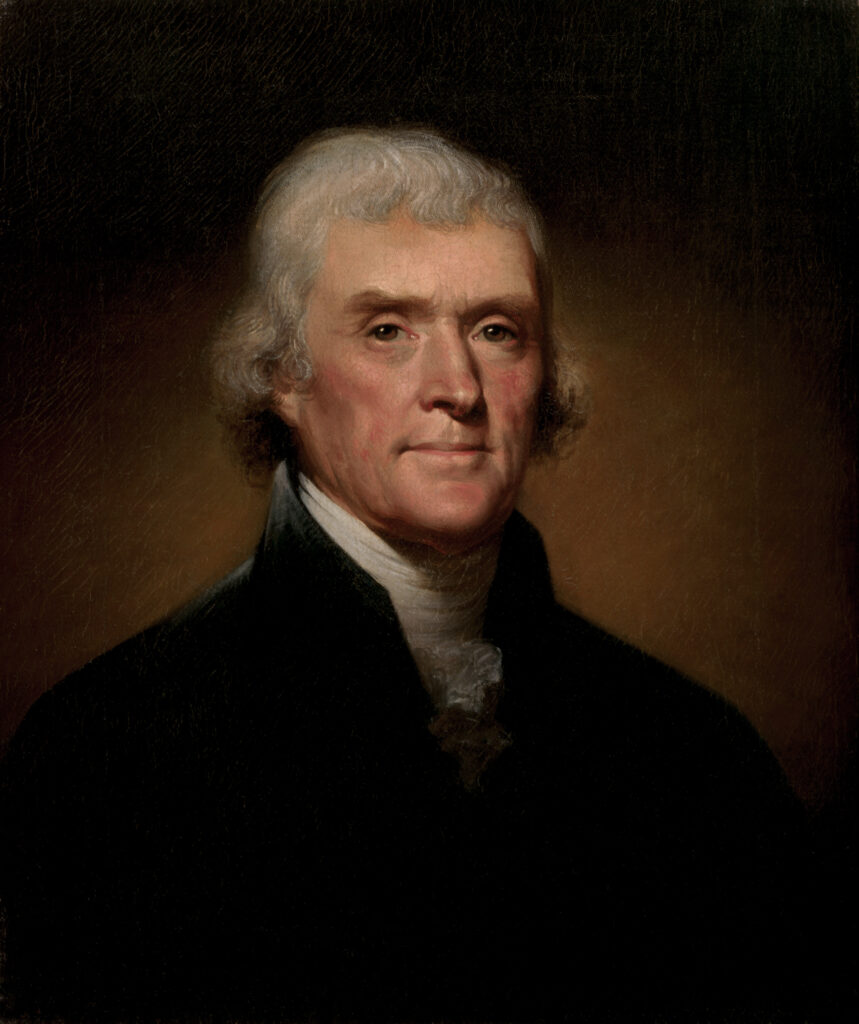

From the very beginning the Lyceum welcomed many renowned Members, including Thomas Jefferson, third president of the United States.

1836

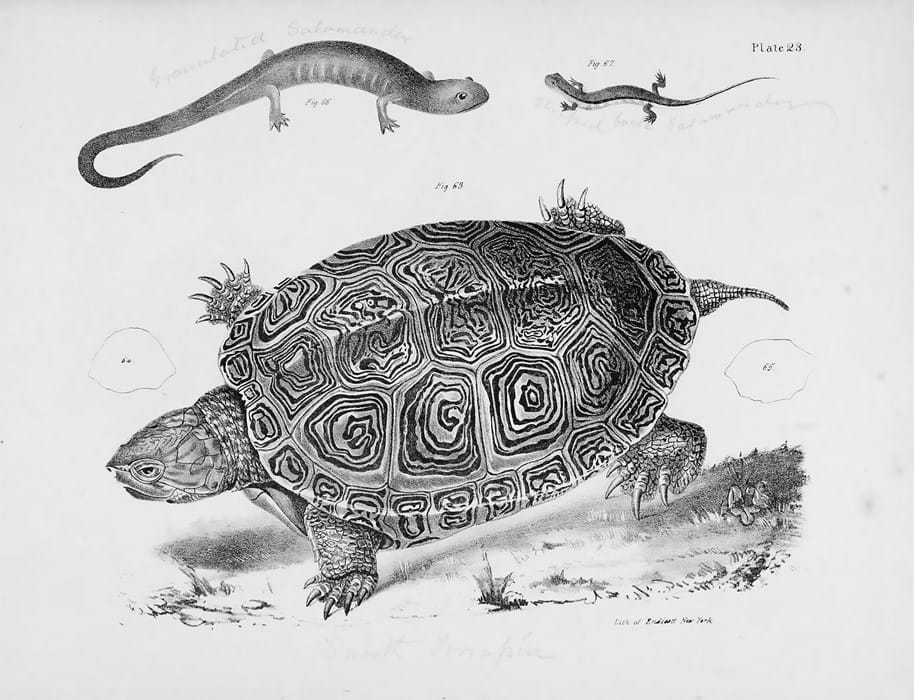

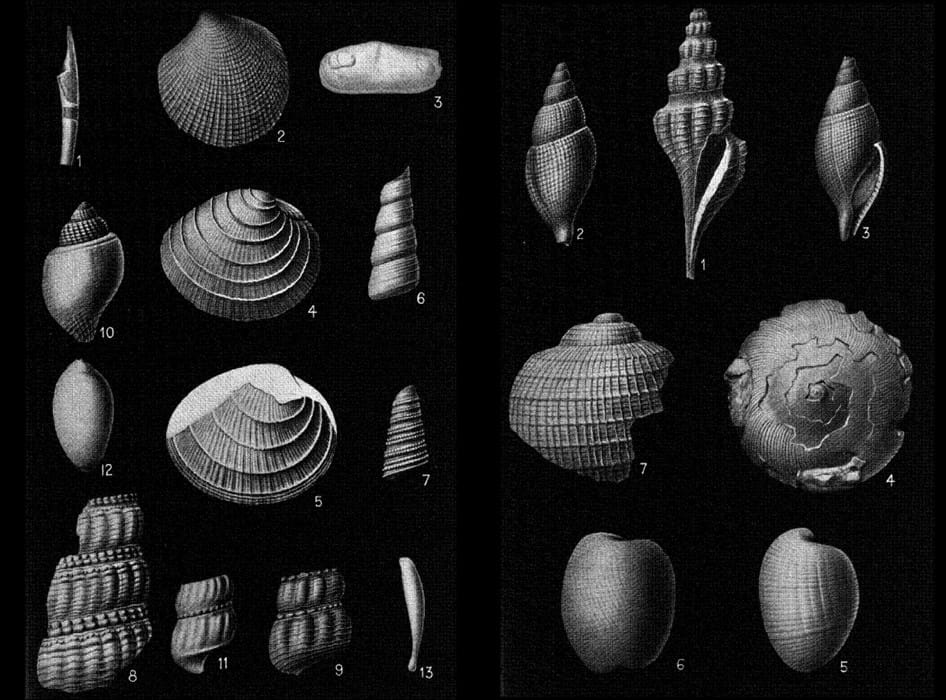

Commissioned by New York State, Lyceum members Lewis Beck, John Torrey and James DeKay led this landmark assessment of the state of New York’s natural resources, including minerals and forests, its flora and fauna. Also this year, Botanist Asa Gray became curator and librarian of the Lyceum; later, as a Harvard professor, Gray was one of Darwin’s lead supporters in the US.

1840

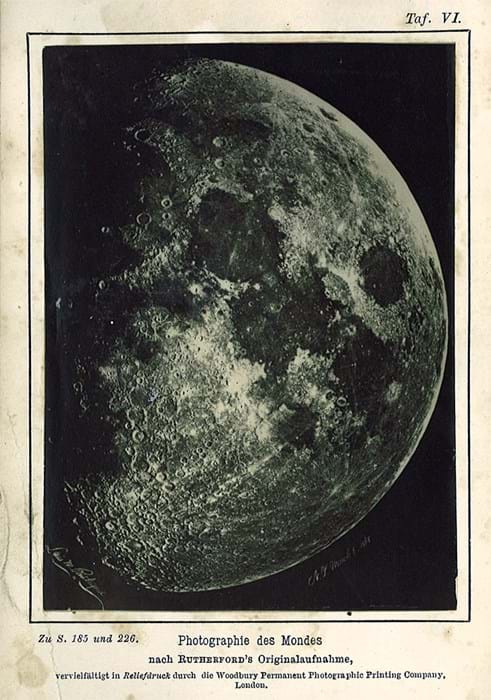

Chemist, physician, photographer, and Lyceum member John W. Draper presented the first photograph, an early daguerreotype, showing details for the moon’s surface at a Lyceum meeting on March 23.

1850-1900

From 1850-1900, Academy membership grows with some of the greatest names in science, welcoming in a new century of discovery.

1859

Renowned geographer, naturalist, explorer and philosopher Alexander von Humboldt was among the early Members of the Academy.

1865

In 1865, Academy Member Lewis M. Rutherfurd, who invented the first telescope designed for astrophotography, published one of the first high quality images of the moon.

1866

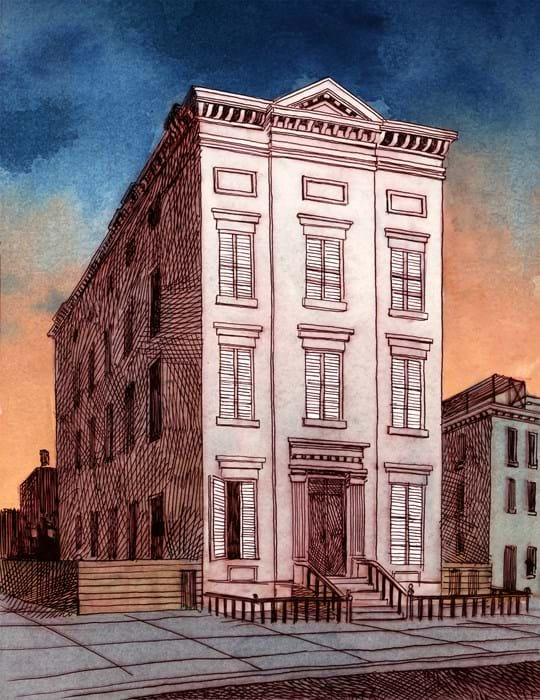

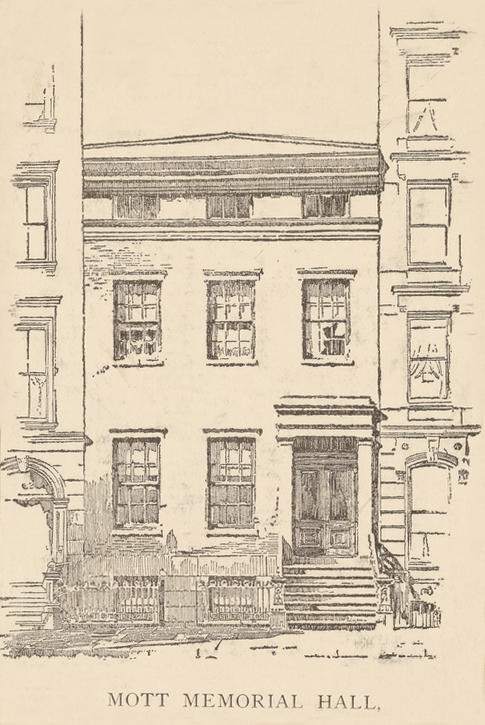

On the night of May 21, 1866, fire broke out in the building next door to the Lyceum headquarters on 14th Street. It soon engulfed the entire block, destroying the Lyceum’s library, as well as its collection—including John James Audubon’s Birds, John Draper’s chemistry apparatus, and an unrivaled mineralogical cabinet—dashing hopes of establishing a natural history museum and leading the Lyceum to move to Mott Memorial Hall at 64 Madison Avenue. The Lyceum persevered, turning this catastrophe into an opportunity to adapt to the changing landscape of science.

1868

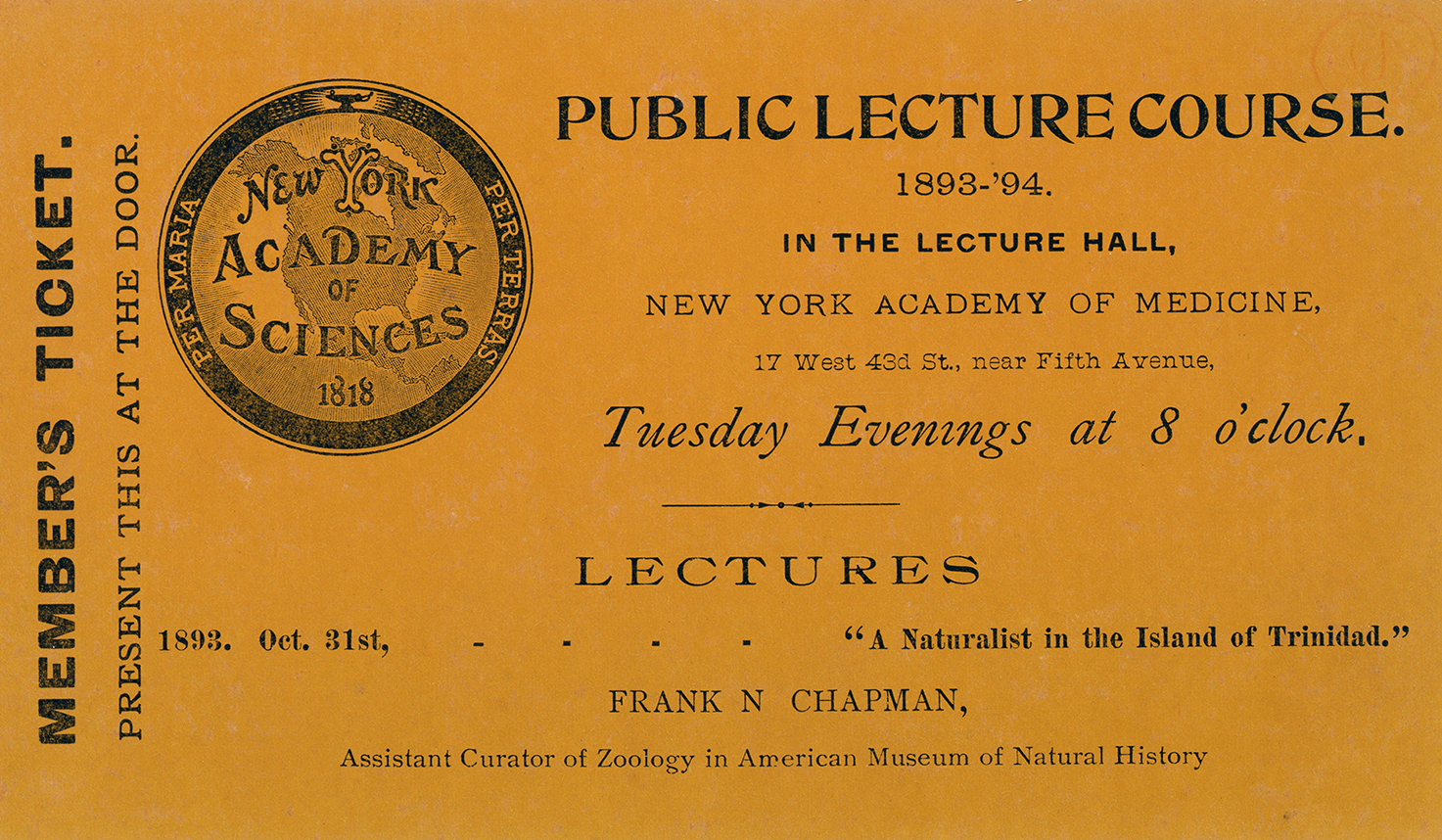

Members of the Academy played key roles in founding a number of important institutions across the city of New York, including the American Museum of Natural History.

1876

In the late 1800s science was becoming more specialized. Professional societies began to form, and natural history no longer represented a unified body of knowledge. In order to reflect the larger scope of scientific disciplines represented in the organization, such as Chemistry, Engineering, and Technology, the Lyceum changed its name to The New York Academy of Sciences on January 5, 1876, and created specialist sections under the Academy’s umbrella.

1877

In keeping with its egalitarian principles, the Lyceum voted to begin inviting women to attend its meetings and to become members. Geologist and anthropologist Erminnie A. Smith became the first woman elected to Academy membership.

1887

Academy members also played important roles in national organizations, coordinating the first New York meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an event that gave the local scientific community visibility on the national stage. At the AAAS meeting, Albert A. Michaelson and Edward W. Morley made public their experiment disproving the existence of an “ether” through which light was through to travel in the form of waves. This shocked the audience—and paved the way for Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity.

1891

The Academy created the Scientific Alliance, an organization that united New York’s scientific clubs and societies—and began publishing the Bulletin to announce meetings and foster collaboration among member groups. Through these efforts, the Academy emerged as a leader.

1892

Scientist, inventor, engineer and Academy member Alexander Graham Bell opened long-distance telephone service from New York to Chicago in 1892.

1894

The Academy launched a series of annual exhibitions showcasing the research of its members and of other institutions in New York City.

1900-1950

The turn of the century brought in a new president to the Academy, along with new conferences and initiatives.

1906

Nathaniel Britton was elected president of the Academy in 1906. Britton had been instrumental in founding the New York Botanical Garden, chartered in 1891, and had served as its first director. This year, the Academy moved into rooms at the American Museum of Natural History, where it maintained its offices until 1950. Academy members were among the Museum’s founders.

1913

Britton launched the Academy’s ambitious survey of Puerto Rico—the first of its kind—by marshaling the expertise of members in diverse disciplines: geology, meteorology, oceanography, archaeology, anthropology, botany and zoology. Though it began as a small-scale botanical and entomological exploration, it grew into a multi-year project, publishing 19 volumes and earning the Academy a reputation for scientific excellence.

1916

Serbian-American physicist and Columbia professor Michael Pupin was elected Academy president.

1935

Eunice Miner, a research assistant at the American Museum of Natural History, joined the Academy with just over 300 members. Miner became the Academy’s Executive Director in 1939 and through legendary energy and ambition, expanded membership to more than 20,000 by 1967.

1938

Two pioneering conferences—one on electrophoresis in 1938, the other on the internal composition of stars in 1939—established the Academy conferences in the eyes of the international scientific community.

1942

The Academy published the book Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis, by Gregory Bateson & Margaret Mead. Both Academy Members, Bateson and Mead compiled over 700 photographs depicting their cultural studies in Bali. Read the book here.

1946

In January of 1946, the Academy held the first-ever large scientific conference on antibiotics, only two years after the discovery of streptomycin. Proceedings from this groundbreaking conference were published in the September 1946 volume of Annals.

1948

The Academy launched the first Science and Technology Exposition, New York City’s science fair.

1950-2000

The Academy spent the entire latter half of the 20th century in its newly acquired Woolworth Mansion building, the longest period to date that the Academy remained in a single location, which helped to provide stability and promote advancement.

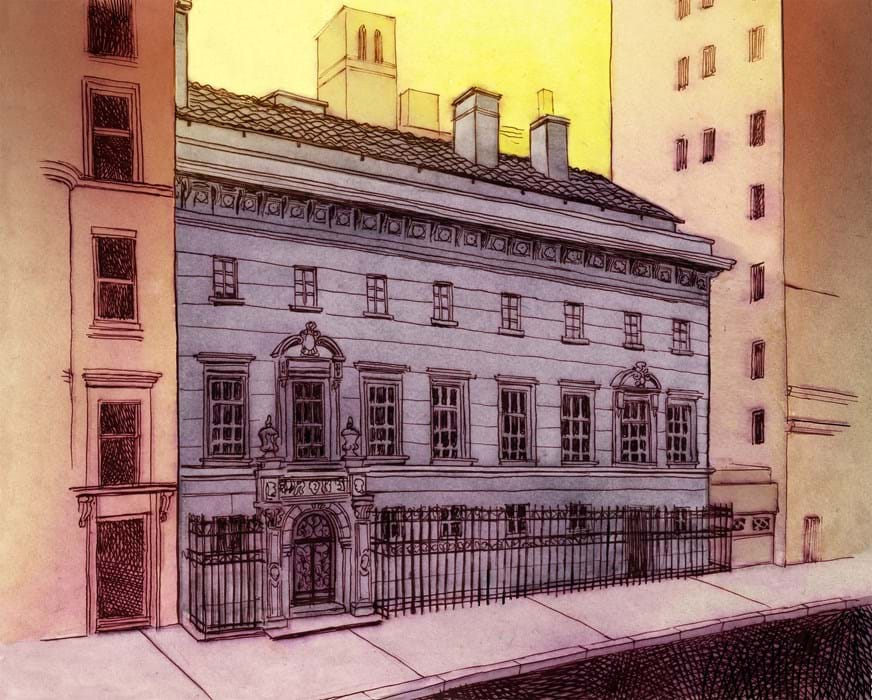

1950

After hearing a talk by Eunice Miner in the late 1940s on the Academy’s need for a home, Norman Woolworth donated the Woolworth Mansion on East 63rd Street. This became the Academy’s headquarters for the next 50+ years.

1961

The Academy launched The Sciences, seven-time National Magazine-award-winning science publication for an audience of both experts and lay readers; publication continued until 2001.

1964

Leaders of the Academy had long been aware that advances in health and living could only be secured by developing a new generation of scientists and science-savvy adults. The launch of the Junior Academy fostered the next generation of scientist-researchers, including George Yancopoulos, co-founder of cutting-edge biotech company Regeneron.

1966

Leading anthropologist Margaret Mead became a Vice President of the Academy in the 1960s.

1970s

The first African-American woman to receive a PhD in Chemistry in the U.S., Marie Maynard Daly had a distinguished career in biochemistry and was an Academy Member, as well as a Member of the Academy’s Board of Governors.

1978

Charlotte Friend, renowned for establishing that cancer could be caused by a virus, became the Academy’s first female president.

1979

The Science in Research Training Program was established, giving high school students an opportunity to do research in real laboratory settings. The Academy also established the Albert Einstein public lecture series, given by notable scientists including Sydney Brenner, Freeman Dyson, Susumu Tonegawa and Steven Weinberg.

1983

When many were still fearful of addressing the AIDS crisis, the Academy took the lead and hosted the first major scientific conference on AIDS in December of 1983. Conference proceedings were published in a December 1984 volume of Annals.

1987

The Academy published a fifth volume of reports from the Moscow Refusnik Seminar, papers by persecuted scientists from the Soviet Union and by concerned colleagues.

1988

Physicist Andrei Sakharov and Chinese dissident Fang Lizhi credited the Academy for the coordination of international pressure around the human rights of scientists that resulted in their release. Both made the Academy their first stop during U.S. visits.

1993

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, the Academy held science fairs for high school students, continuing a long tradition begun in the 1940s.

1997

With increasing focus on public health and policy, the Academy convened a landmark conference on the effects of cocaine on the developing brain.

2000-2020

Moving into the 21st century, the Academy returned to its roots in lower Manhattan and celebrated its bicentennial, marking two centuries of advancing science for the public good.

2005

Ellis Rubinstein became Academy President and CEO.

2006

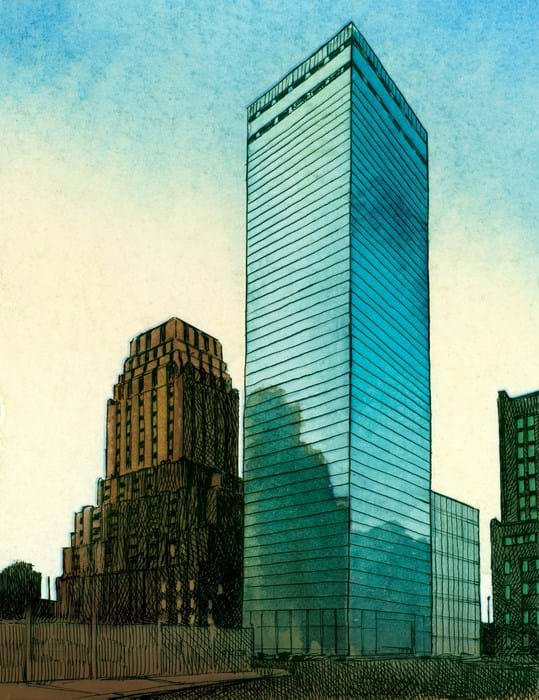

The Academy moved downtown as the first tenant of the new World Trade Center at 7 WTC, 250 Greenwich Street—four blocks from its birthplace on Barclay Street.

2007

In November of 2007 the first-ever Blavatnik Awards for Young Scientists were announced at the Academy’s annual gala. The Blavatnik Awards were created to honor exceptional young scientists and engineers by celebrating their achievements, recognizing their future potential, and providing them with unrestricted funding.

2008

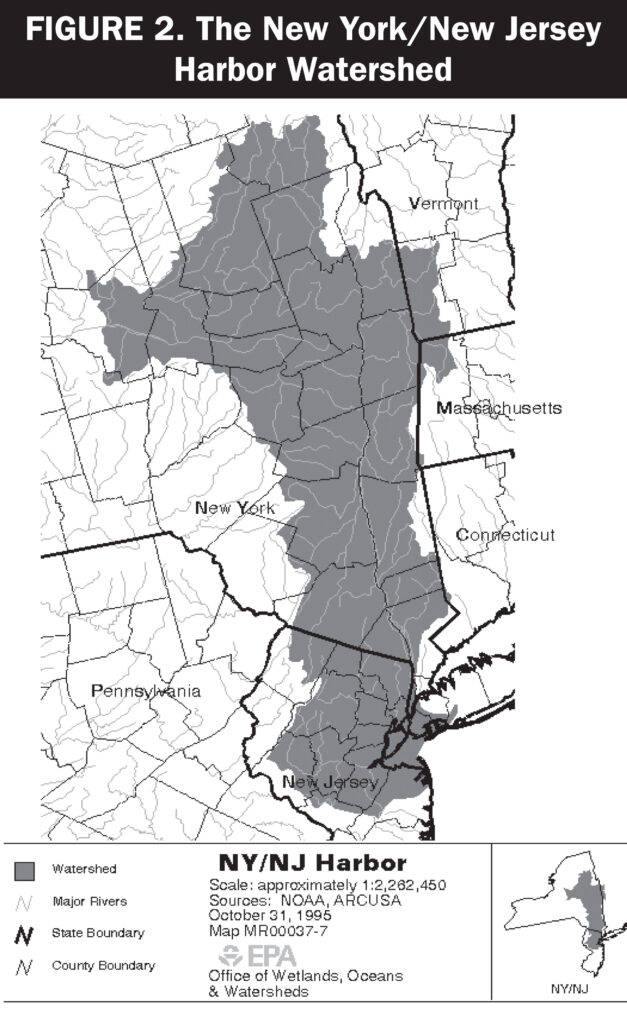

The Harbor Project achieved consensus among 70 stakeholder organizations on the industrial sources of contaminants in New York Harbor and ways to protect the watershed.

2010

In February of 2010, the Academy published one of its most downloaded volumes of Annals, “The Biology of Disadvantage: Socioeconomic Status and Health.”

2012

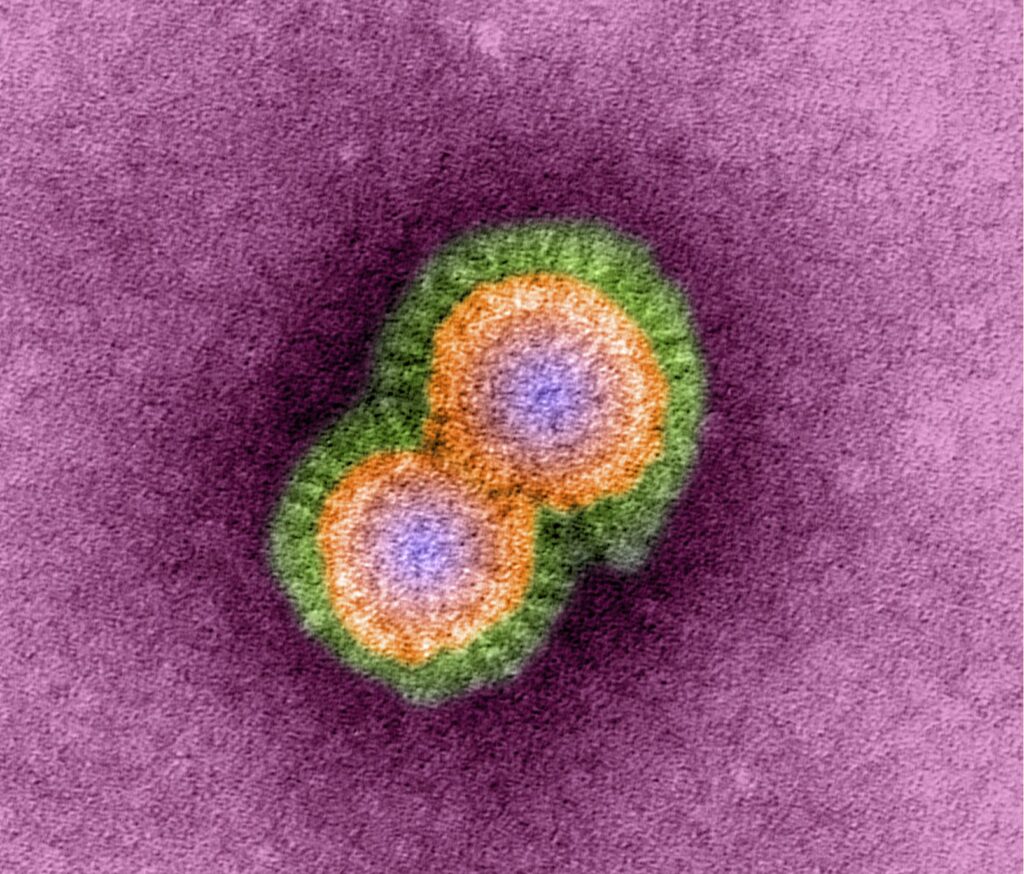

The Academy convened a panel discussion to debate perceived censorship of highly controversial studies with the avian influenza virus H5N1.

2014

On September 22, 2014, the Academy announced the Global STEM Alliance before a packed audience at the United Nations. The programs aimed to improve the STEM pipeline with a focus on mentoring and inspiring students and scientists at all stages. The GSA has evolved into Academy Learning [ck], which continues to be dedicated to STEM education for K-12 students and serves to keep the scientific career pipeline filled with promising young minds.

2017

The Academy turned 200 years old, celebrating two centuries of bringing together extraordinary people to drive solutions to society’s challenges by advancing scientific research, education, and policy.

2020

On March 12, 2020, the Academy held a webinar “What You Need to Know About the New Coronavirus.” Attendance exceeded 5,000 participants. The Academy continued to provide important, unbiased scientific information on the spread of SARSCoV-2, and the development of therapeutics and vaccines against the coronavirus, convening nearly 25 events in the first months of the pandemic. In so doing, the Academy built on a proud tradition of bringing together diverse, international stakeholders to address global issues as was done with antibiotics in 1946, AIDS in 1983, SARS in 2003, and H1N1 (swine flu) in 2009.

2020-present

As the world was grappling with the COVID pandemic, the Academy introduced Nicholas B. Dirks as its next president, at a time when advancing science for the public good was crucial.

2020

In June 2020, Nicholas B. Dirks took the helm as President and CEO of The New York Academy of Sciences.

2022

The Academy introduced the International Science Reserve (ISR), a global network of scientific experts committed to collaborating across borders to accelerate solutions to help mitigate global crises that may arise from another pandemic, a cyberattack, or disasters associated with climate change. In its first year, more than 2000 scientists from 100 countries joined the ISR community.

2023

From May 23-24, the Academy presented another groundbreaking first—the first convening of experts to address “The New Wave of AI in Healthcare.” This was just the first of many upcoming Academy endeavors, including a multi-year AI fellows-in-residence program, that aims to examine the potential applications of AI in various sectors for the public good.

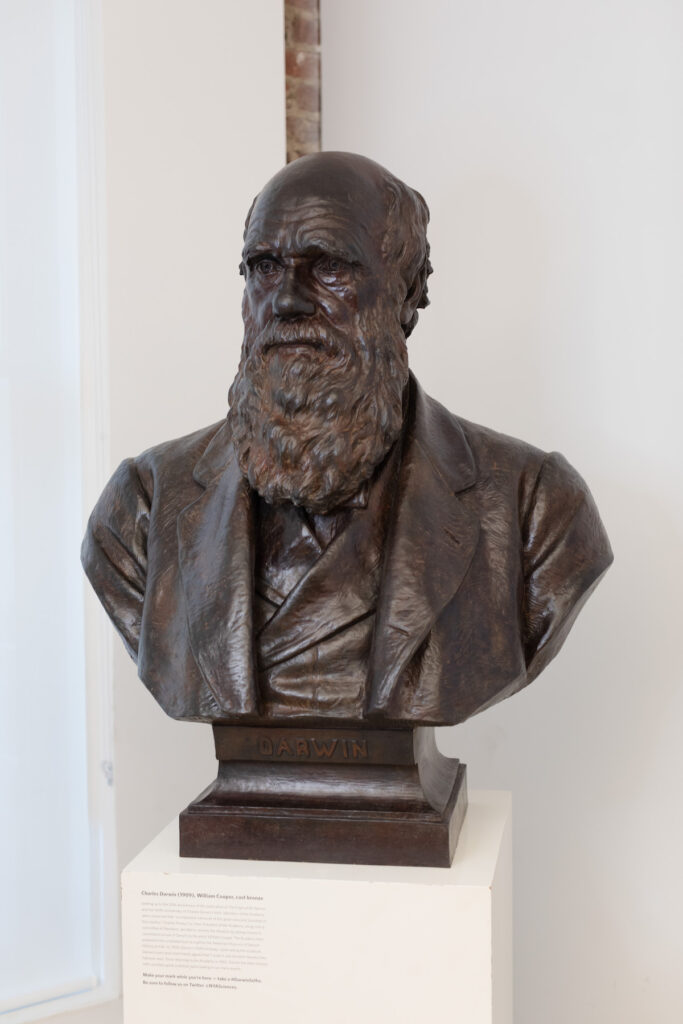

Then, on September 14, the Academy christened its newest home by welcoming the Academy community to 115 Broadway to hear stimulating discussions about the future of science and to engage in hands-on science activities. The spirit of discovery of Charles Darwin—an early Member of the Academy—is very much alive to this day. A sculpture commissioned by our Members welcomes staff and guests alike in the lobby of our latest headquarters.