The New York Academy of Sciences’ Scientist-in-Residence Student Showcase is an opportunity to explore scientific innovations taking place in New York City.

Published June 25, 2025

By Jennifer Atkinson

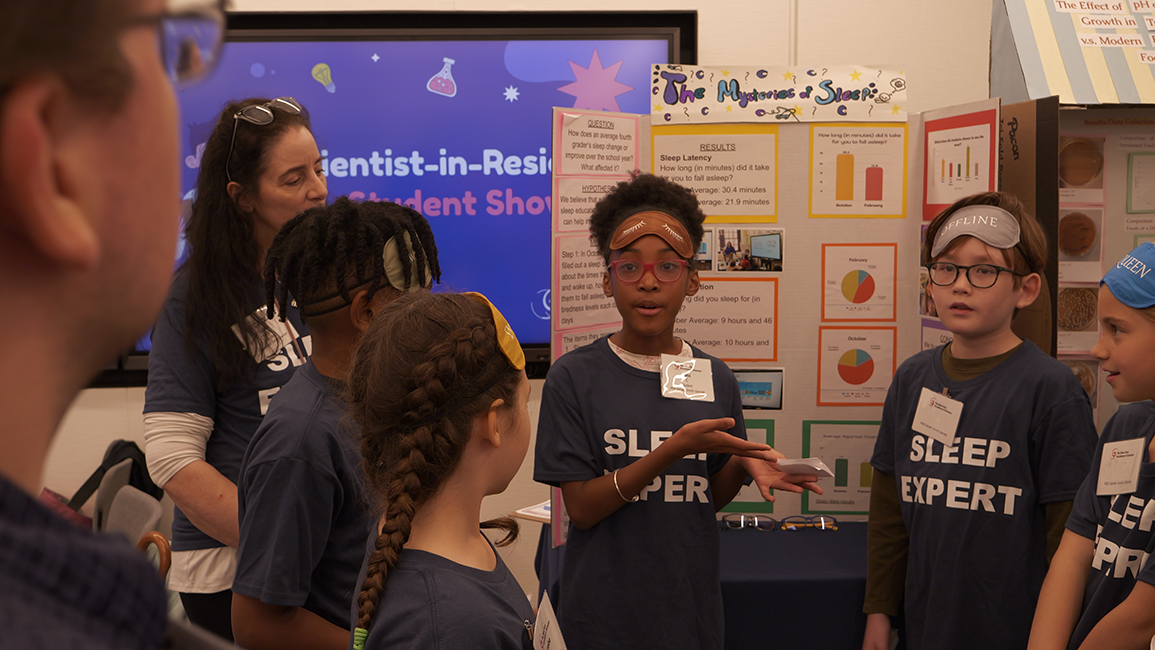

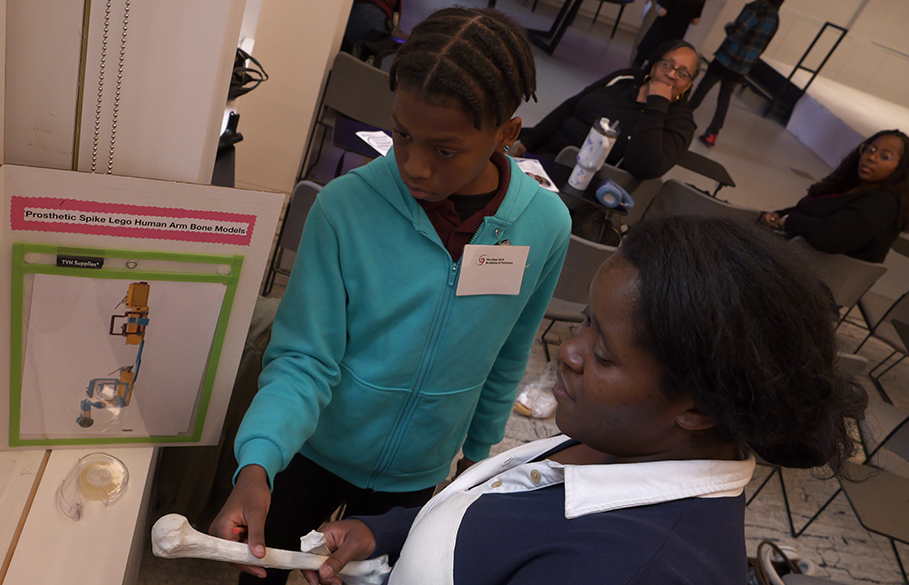

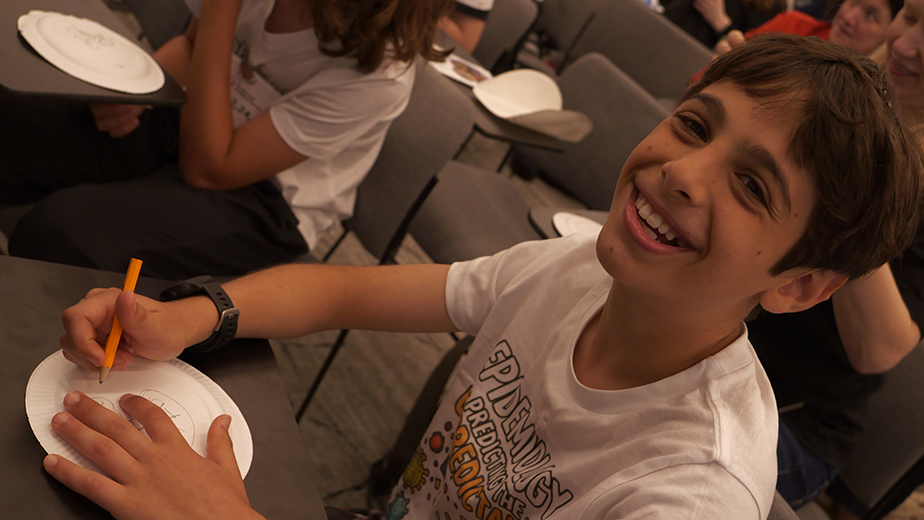

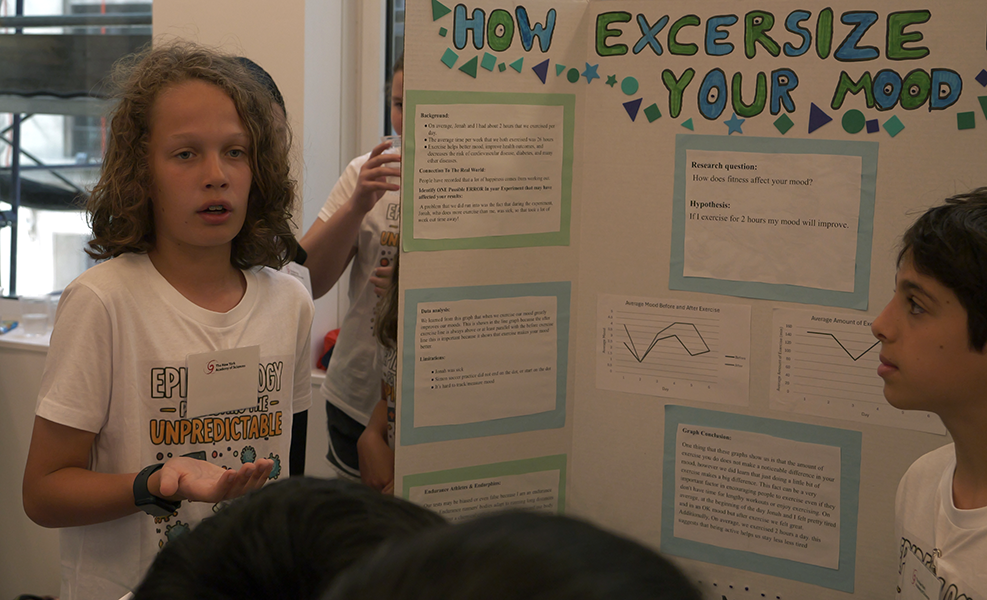

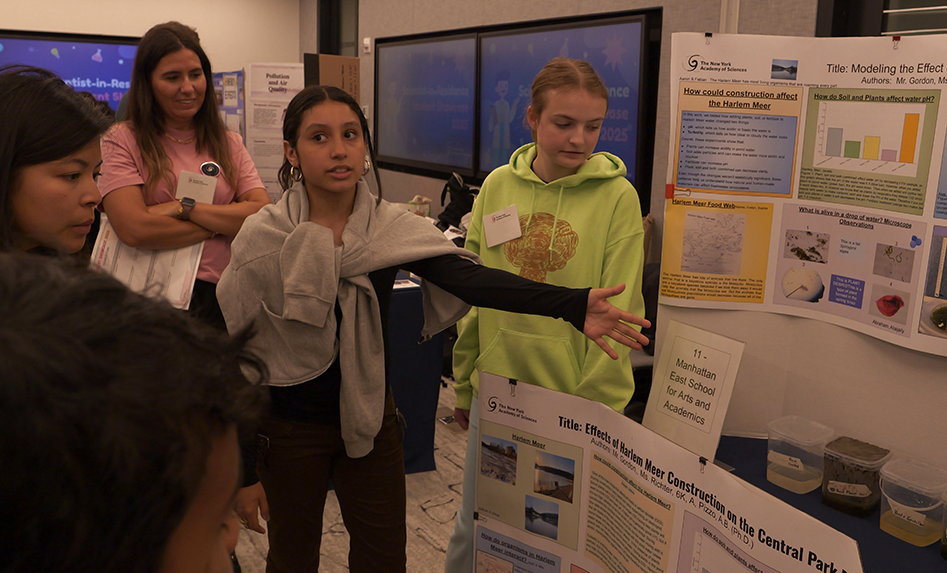

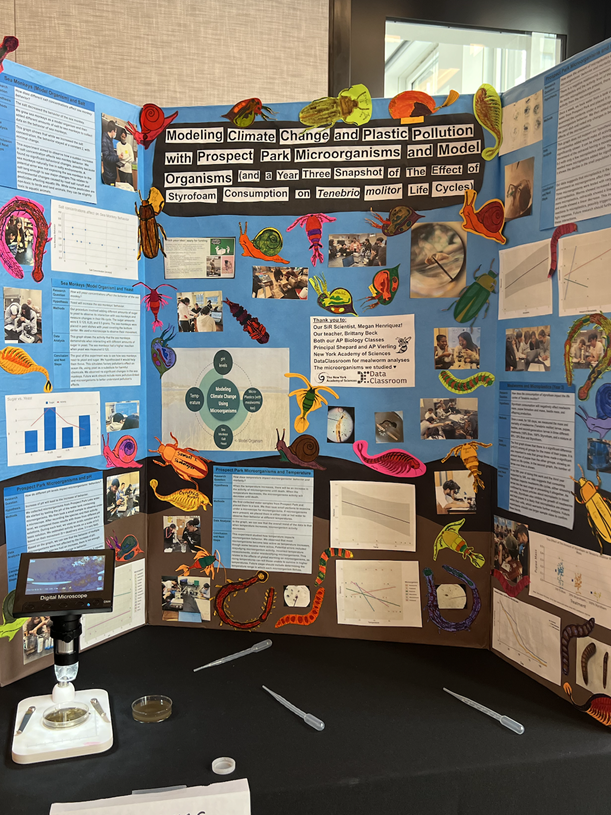

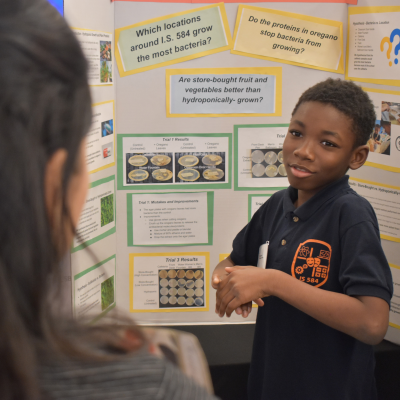

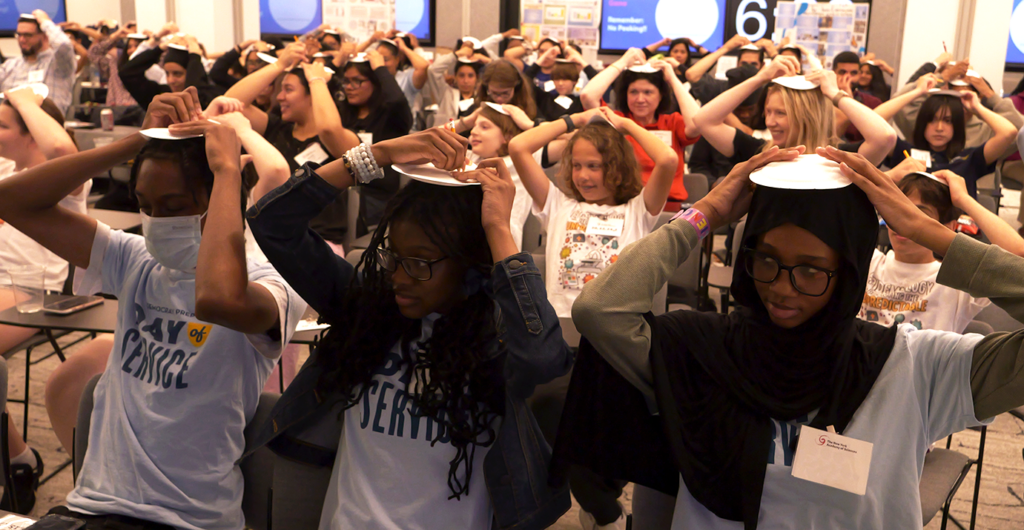

Students of all ages buzzed about posters and 3D dioramas of every shape, size, and color. In the air was a sense of nostalgia, one that harkened back to school science fairs from our youth. Students dressed in costumes for their presentations, some looking like the stereotyped “mad scientist” in white lab coats and goggles. Others took a different approach, dressing to resemble their projects, with one student wearing a sleep mask with “Nap Queen” embroidered on it.

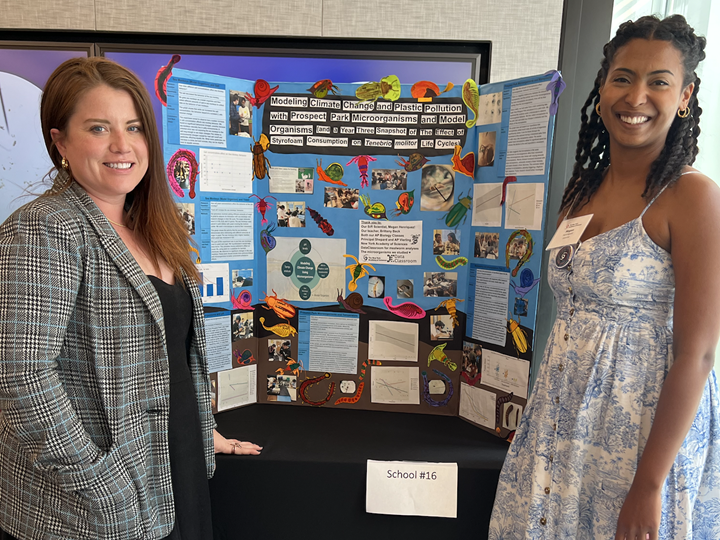

The Scientists-in-Residence program, created in cooperation with the New York City Department of Education, offers public school students in elementary through high school the chance to bring their scientific imaginations to life by matching them with a scientist from The New York Academy of Sciences’ (the Academy’s) distinguished roster of graduate students and STEM professionals. The scientist works with a partner teacher to devise a project for their school group to work on throughout the year, culminating in a showcase each May to present their findings.

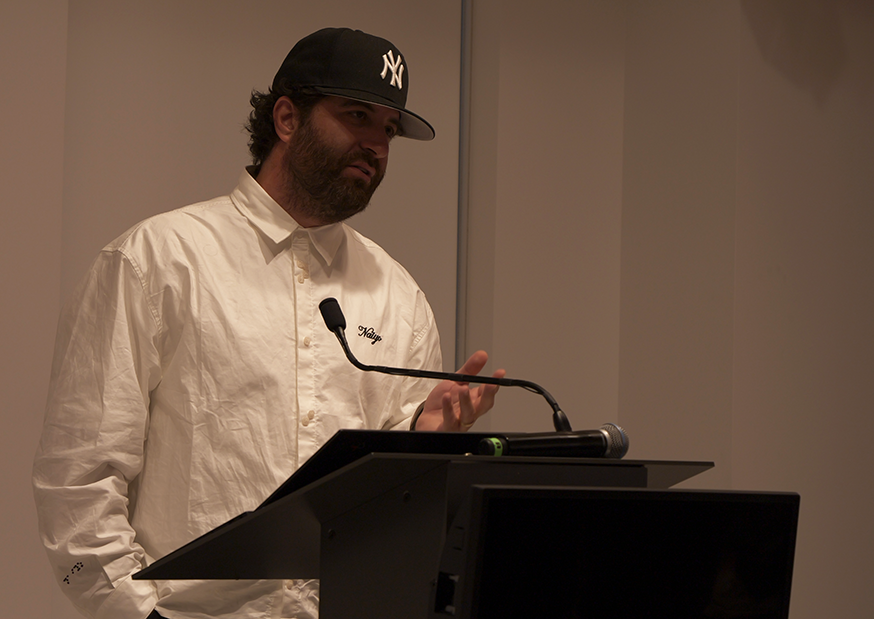

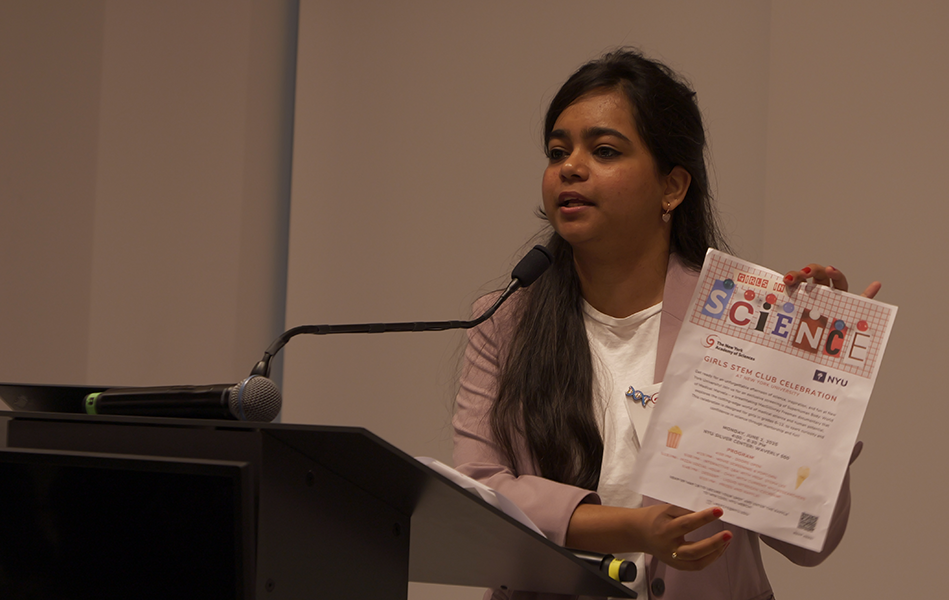

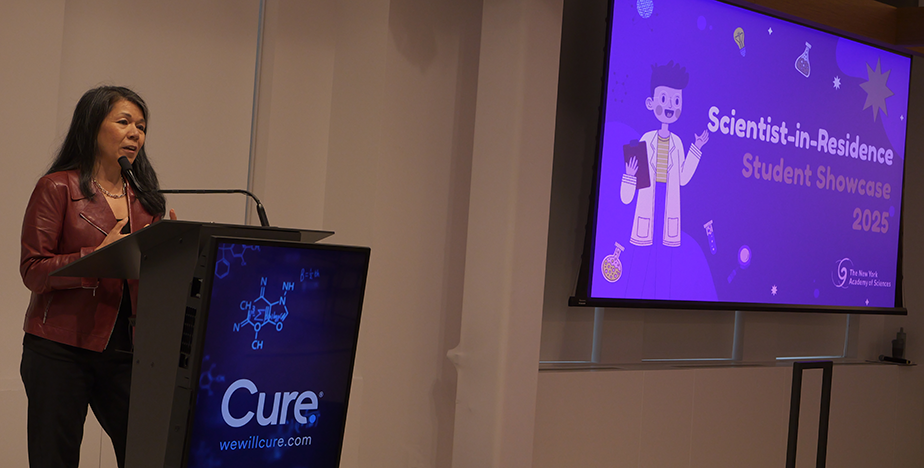

This year’s showcase, which was held on May 29th and 30th, brought nearly four hundred students from 41 schools across NYC together to celebrate their scientific discoveries. Special guest speakers, all of whom shared powerful messages of encouragement and inspiration, included:

- Seema Kumar, CEO of Cure and member of the Board of Governors at The New York Academy of Sciences

- Rita Joseph, New York City Council Member

- Roy Nachum, Co-Founder of Mercer Labs

- Cindy Lawrence, Executive Director of MoMath

- Magdia DeJesus, Director of Scientific Strategy and Business Operations, Pfizer

- Will Lenihan, Curator, Brooklyn Botanic Garden

- Susanna Ling, Senior Vice President Sponsorships, Partnerships and Industry Programs, Cure

Scientific Innovation Has No Bounds

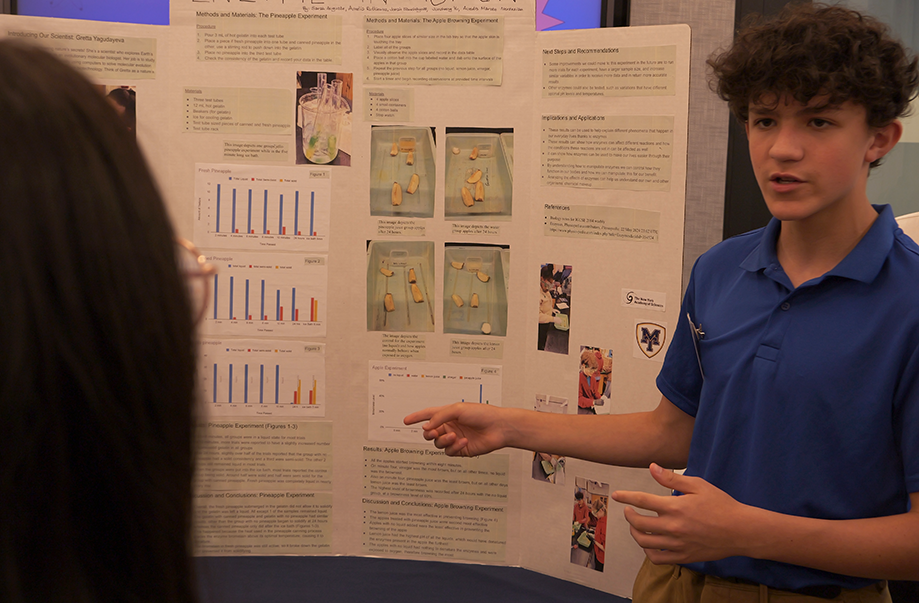

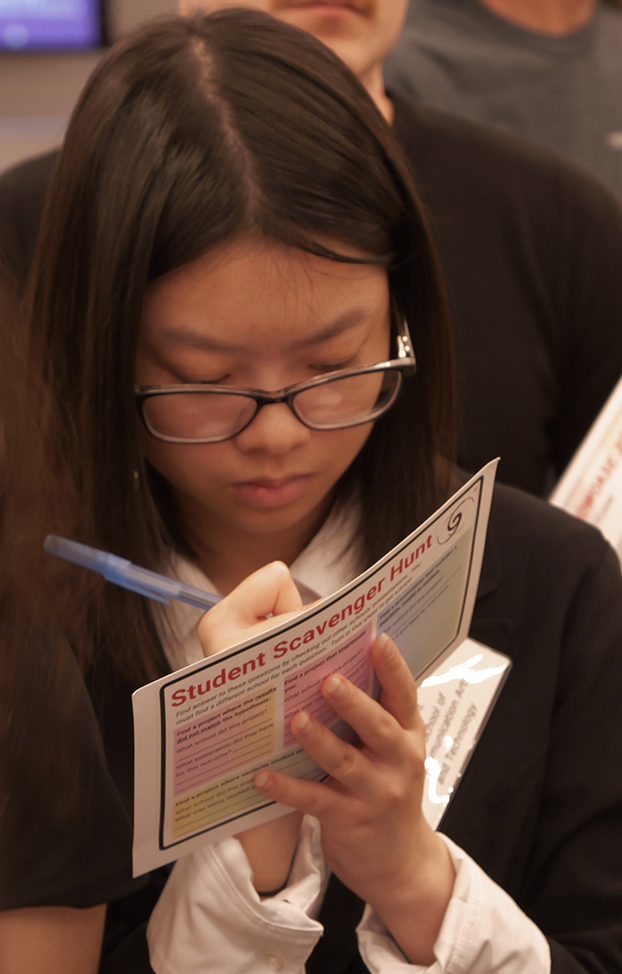

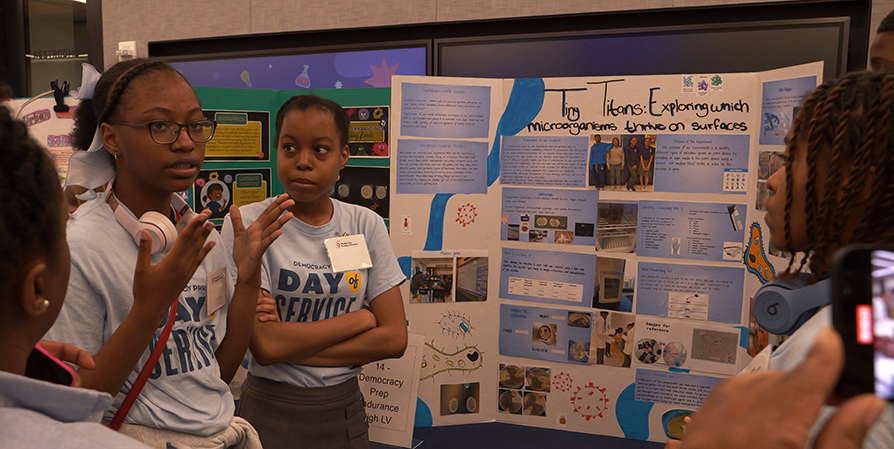

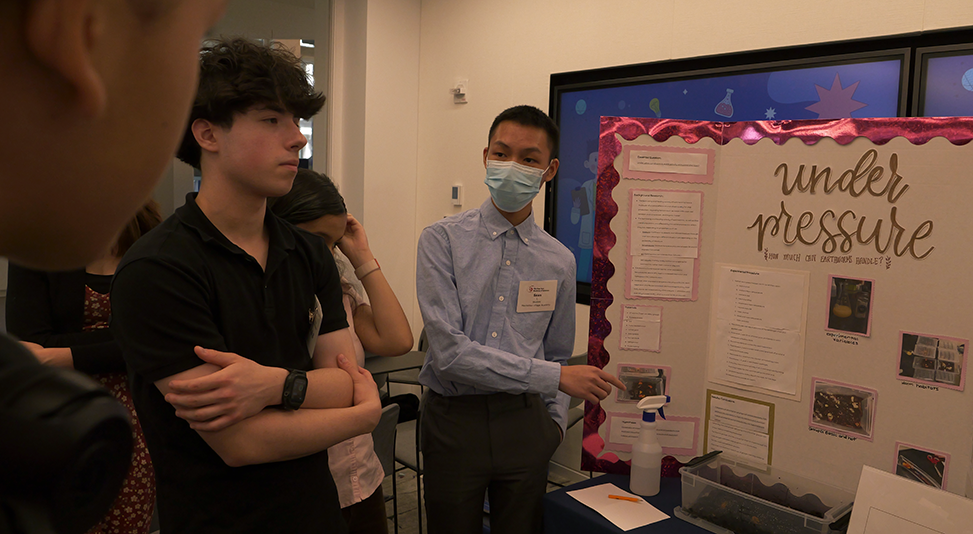

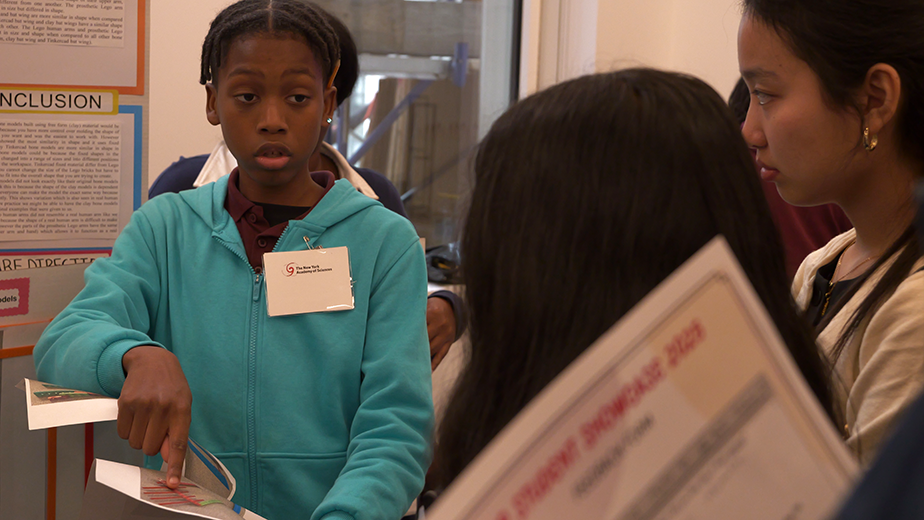

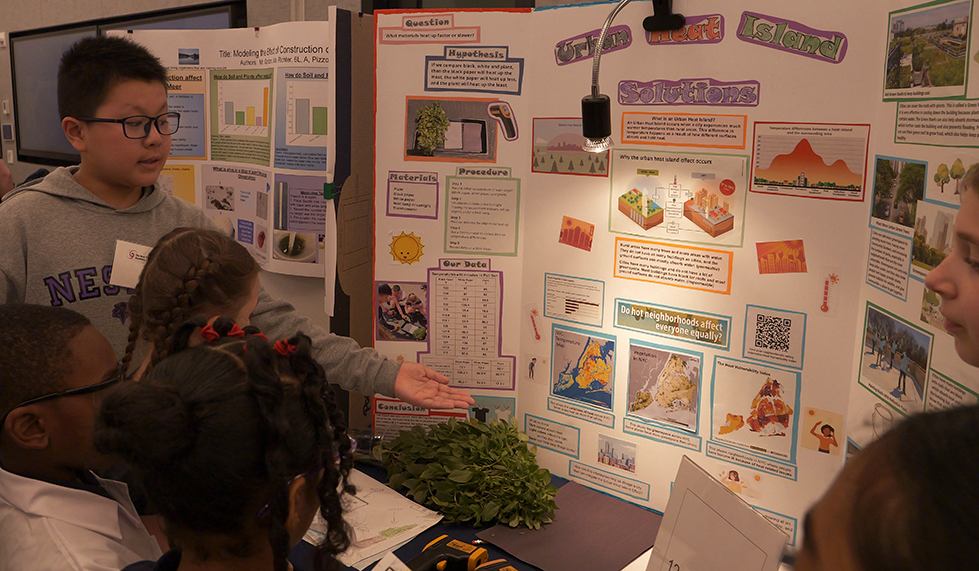

During the poster sessions, older and younger students engaged with each other by listening to their peers’ presentations, providing an opportunity for students to learn from one another, not just a teacher or a scientist. Each student was provided with a scavenger hunt sheet to take specific notes about other groups’ projects, many of which ranged in complexity and subject.

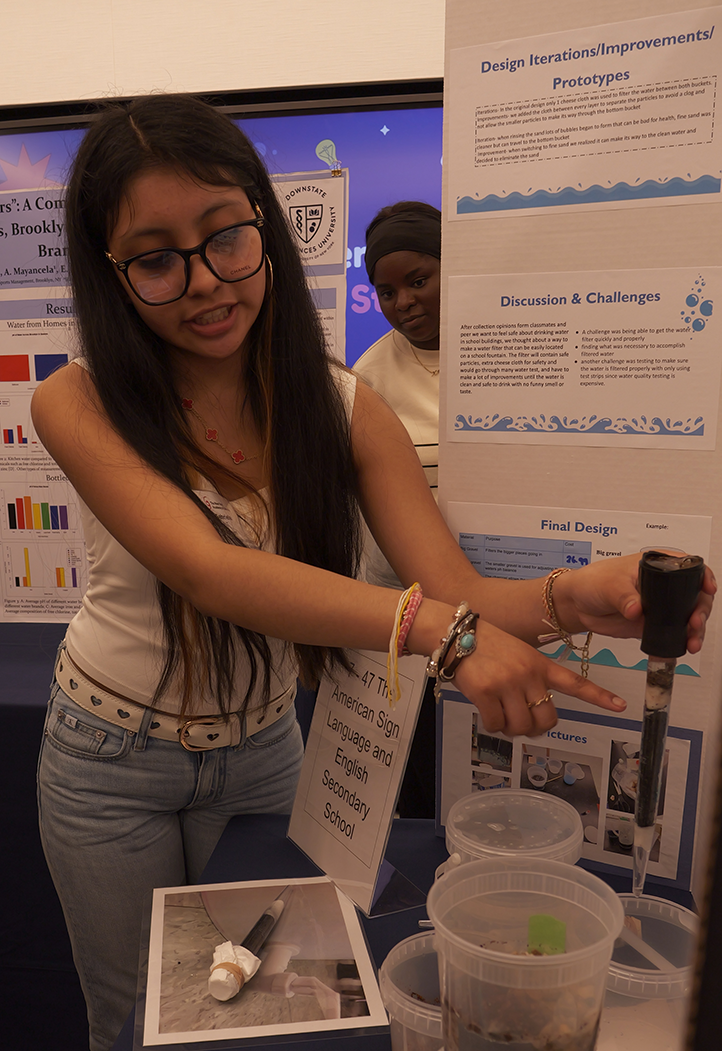

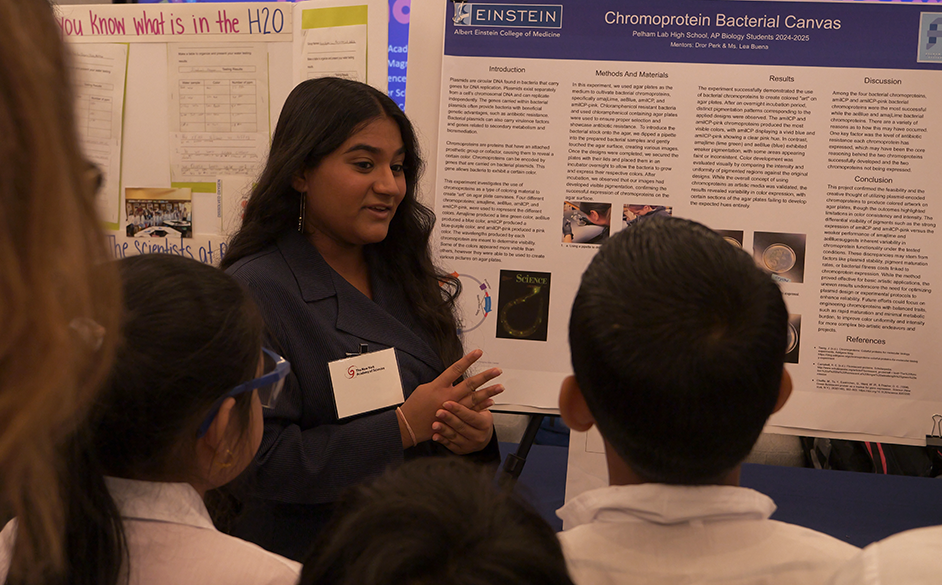

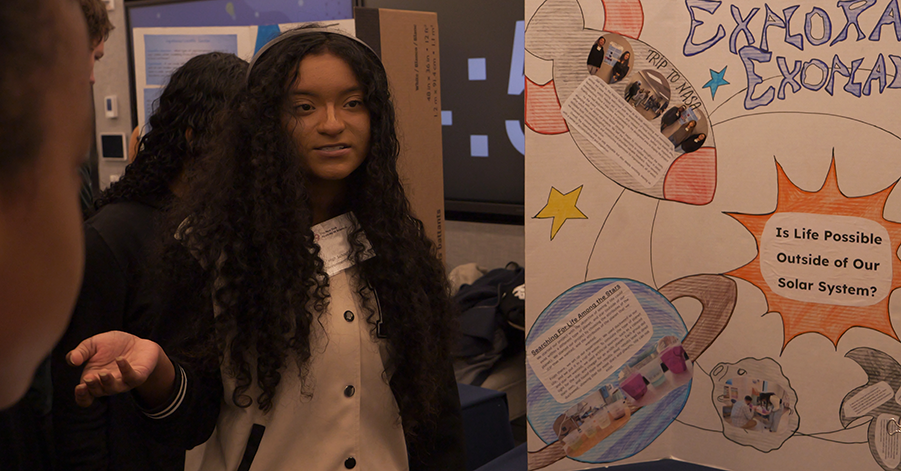

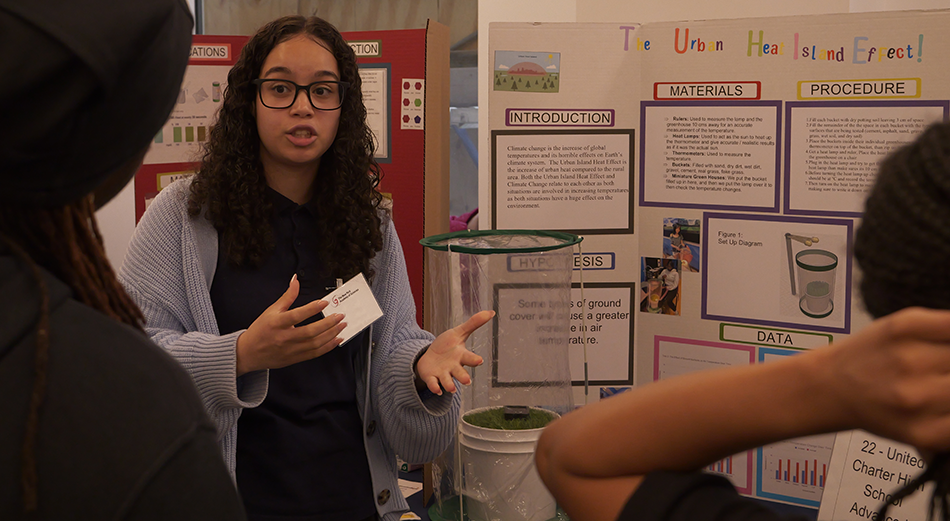

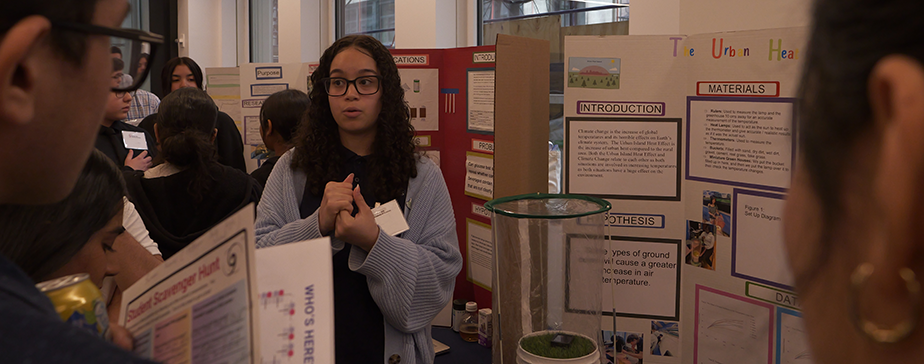

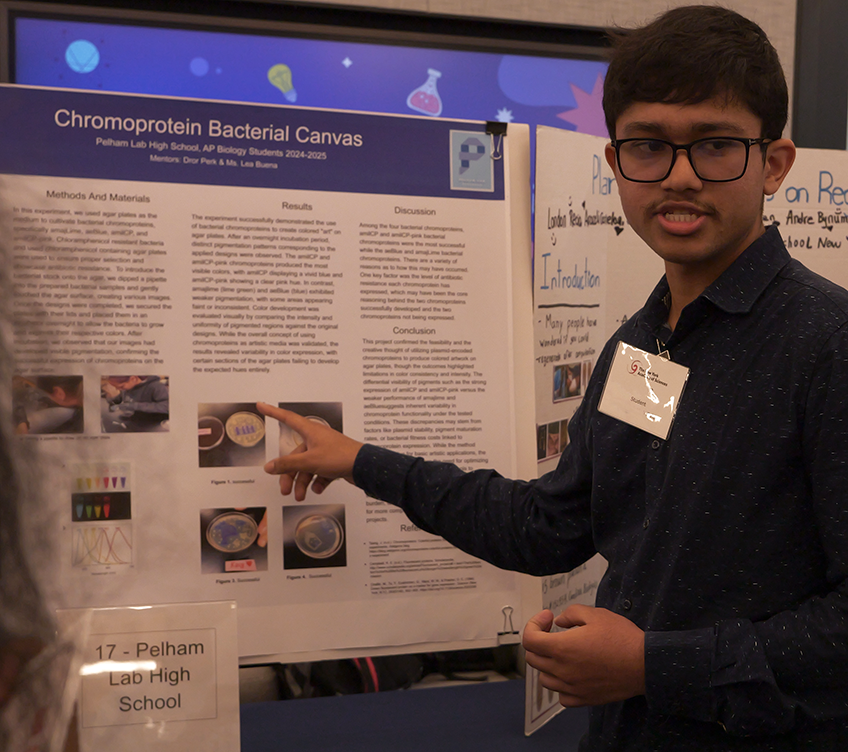

Some projects tackled intricate topics such as bacterial growth in fermented foods, growing crystals from DNA, planarian secrets on regeneration, the study of sleep, and the Urban Heat Island Effect. This also gave students a chance to better understand their own home, New York City—as several school groups studied subjects that directly impacted their lives as New Yorkers, such as how air pollution affects the pH of drinking water.

The engagement between schools and students of different age groups provided an ideal opportunity for students to learn something new about a subject they had already studied. On numerous occasions, different school groups chose the same project but approached their experiment using distinct methods. They were encouraged to think outside the box—showing that science and creativity go hand-in-hand, but also that one scientific question can have endless answers.

Learning Valuable Lessons

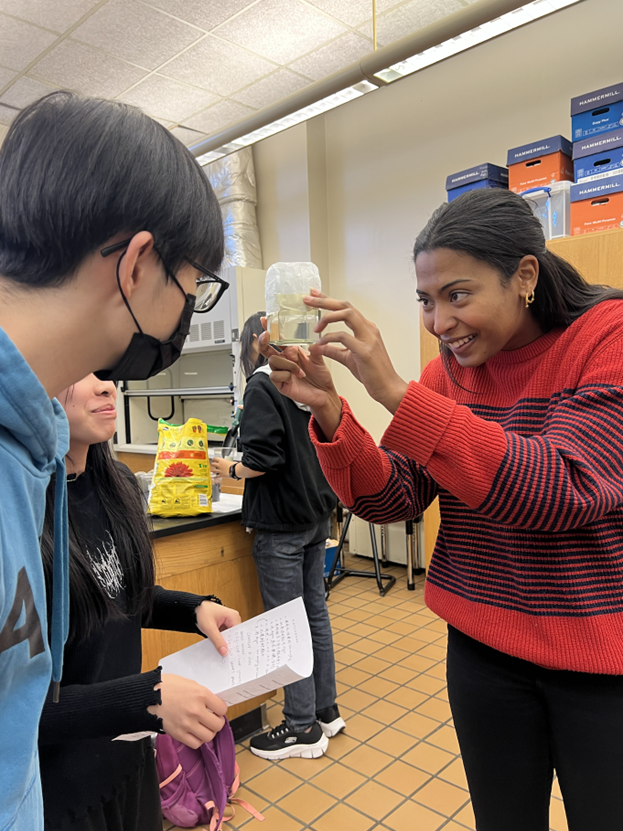

Mentor scientists and teachers also had their own roles to play. Scientists were tasked with teaching their students the rigorous steps of the scientific method, creating hypotheses and sourcing data through surveys, physical collection, or other means. Teachers worked alongside scientists to guide their classes throughout the year. At the showcase, they were given forms to provide feedback to their students about their presentation and public-speaking skills.

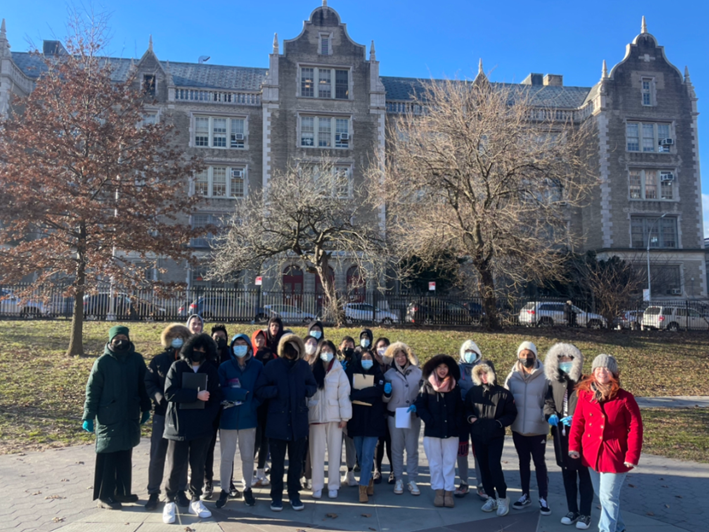

In tandem with their mentor scientists and teachers, students learned valuable lessons about how scientific field work is performed and later communicated to the public, thereby developing a well-rounded toolbox of skills to bring with them into their own future careers as scientists.

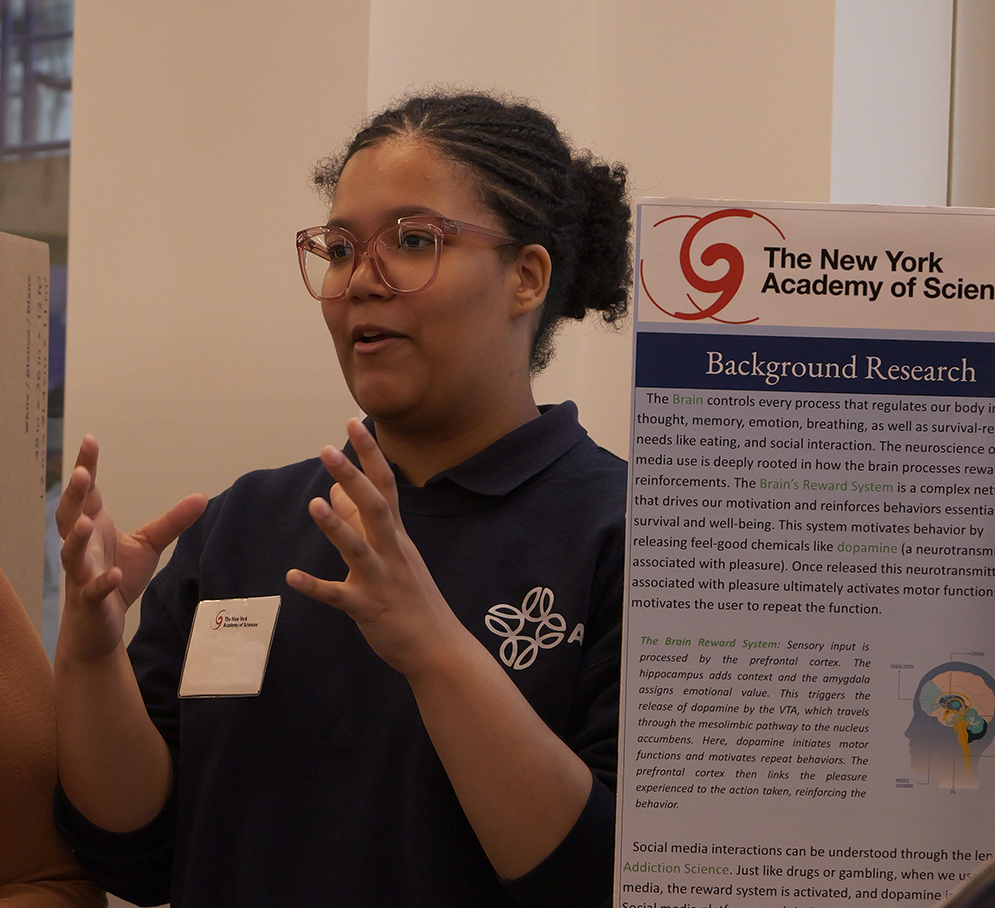

The students themselves were even able to teach both their peers and adults valuable life lessons. One student from Urban Charter High School for Advanced Math and Science described their project on social media and its effects on mental health: “We learned that while it’s so addictive…silencing notifications and using screen time apps helps to moderate social media use. It is crucial to learn how to manage pleasure without the addiction.”

Inclusion in STEM

A big takeaway from this program is that younger generations are passionate about solving everyday problems and making the world a better place for all—and it shows in their hard work.

“One of the things I like most about the program is that students get a chance to know a real scientist—someone who is actively working or studying in a STEM field and isn’t just a name in a textbook or a figure on TV,” said Adrienne Umali, associate director of education for the Academy.

“As they get to know their scientist over the course of a school year, the students start to humanize what it means to be a scientist and in turn begin to build their own STEM identity. A key goal of our program is to foster the idea of belonging in the scientific world—there is no set criteria and you don’t have to look a certain way. Students start to see themselves as scientists, too,” Umali said.

The Scientist-in-Residence program provides the opportunity for scientific exploration and growth for teachers, scientists, and students alike. It serves as an inclusive space for anyone interested in STEM and shows that we are never too old or young to learn something new about our world.

Learn more about the Scientist-in-Residence Program. Applications for scientists and teachers interested in participating are open each Spring.