The recent confirmed case of Chikungunya virus on Long Island marks a significant public health moment for New York. While a single confirmed case is not cause for alarm, it is cause for attention. Climate change is altering disease dynamics faster than many systems are prepared for.

Published October 27, 2025

By Syra Madad, D.H.Sc., M.Sc., MCP, CHEP

New York health officials have confirmed the first locally transmitted case of Chikungunya virus in the United States since 2019, after a Nassau County resident on Long Island tested positive for the mosquito-borne illness. The patient, who developed symptoms in August, had recently traveled within the country but not abroad.

While one confirmed case does not constitute an outbreak, it marks a notable shift in public health realities and a reminder that the changing climate is influencing disease patterns in ways that demand attention and preparation.

Understanding Chikungunya

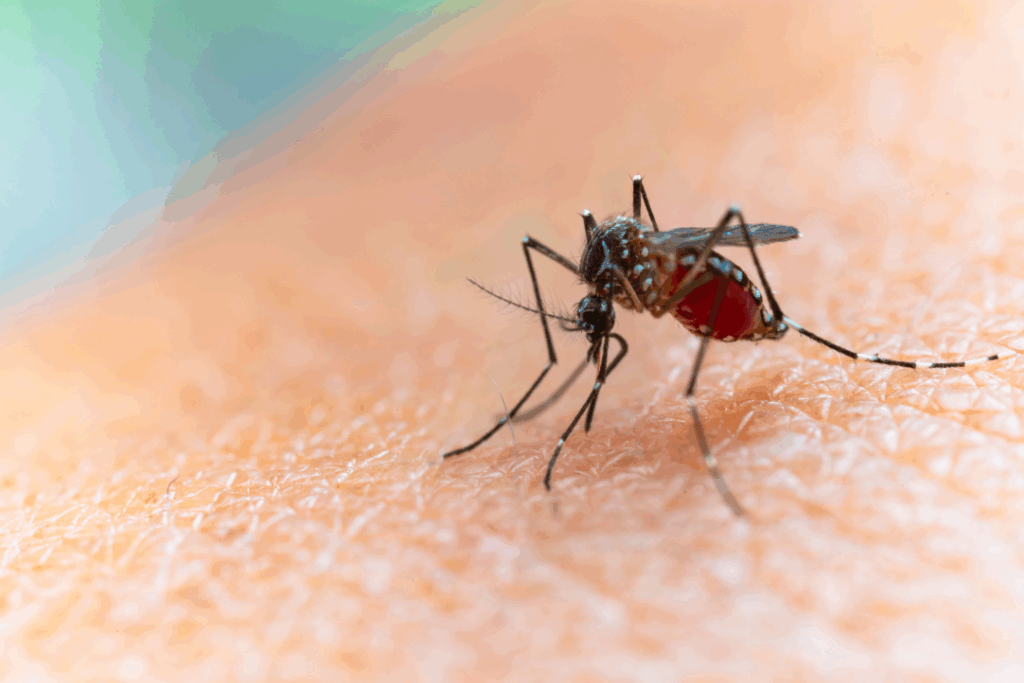

Chikungunya is a mosquito-borne viral illness transmitted primarily by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. First described in Tanzania in the early 1950s, its name derives from the Kimakonde language meaning “that which bends up,” describing the stooped posture caused by severe joint pain.

Typical symptoms include fever, rash, and intense joint pain that may persist for weeks, months, or even years. Although rarely fatal, Chikungunya can cause long-term disability and severely impact quality of life. The United States has reported no locally acquired Chikungunya cases since 2019. Historically, local transmission has been rare, confined to cases in Florida in 2014 and Texas in 2015. Each year, roughly 80 to 100 travel-associated cases are reported nationwide, primarily among individuals returning from the Caribbean, South America, and Asia. Before 2006, the virus was seldom detected in U.S. travelers, but since becoming a nationally notifiable condition in 2015, surveillance has documented a steady trickle of imported infections.

A First for New York

State officials have verified that the Nassau County case represents New York’s first known local transmission of Chikungunya. Prior to this, all infections detected in the state were travel related.

In August 2025, the Department issued a Health Advisory on Chikungunya virus, reminding healthcare providers of testing and reporting protocols and noting that while the virus is not routinely found in the United States, it can be imported into new areas by infected travelers. The advisory also highlighted Level 2 CDC Travel Health Notices for regions including Bolivia, the Indian Ocean area, and China, where outbreaks have recently occurred. The mosquito vector Aedes albopictus is well established in downstate New York, including Long Island. Its northward expansion, facilitated by warmer temperatures and wetter summers, is a direct reflection of our changing climate.

Climate Change and the Expanding Reach of Disease

Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and longer warm seasons are allowing disease-carrying mosquitoes to thrive in new territories. Climate change doesn’t only warm the planet, it transforms where and when pathogens can circulate.

Around the world, Chikungunya has re-emerged with surprising reach, with local transmission reported this year in parts of France, Italy, and China, in addition to ongoing outbreaks in tropical regions. The Long Island case should therefore be read not as an isolated incident, but as a signal of growing vulnerability. Public health agencies will need to adapt surveillance and prevention systems to meet a future where diseases once considered “tropical” may no longer stay that way.

What New Yorkers Should Know

The risk to the public remains low, according to state health officials, but prevention remains essential — especially during the warmer months when mosquitoes are active, typically from late spring through early fall. New Yorkers can reduce exposure by using EPA-approved repellents such as DEET or picaridin, wearing long sleeves and pants during peak mosquito hours, and eliminating standing water around homes where mosquitoes breed. These precautions should continue until cooler temperatures and the first frosts bring mosquito activity to a halt, usually by October or November. Clinicians are urged to remain vigilant and to consider Chikungunya in patients presenting with unexplained fever and severe joint pain, even in the absence of international travel, as locally acquired infections are now possible.

Preparing Clinicians for a Changing Health Landscape

As climate change reshapes patterns of vector-borne and infectious diseases, clinicians have a vital role to play, not only in diagnosis and treatment, but in public communication. A group of us developed the Climate Health Champions training program to prepare healthcare professionals to recognize and respond to the health impacts of climate change. This initiative helps providers integrate climate-informed care into clinical practice, while equipping them to discuss with patients how rising temperatures and changing ecosystems are affecting their health and well-being.

Clinicians are trusted messengers. By engaging in meaningful conversations about the connections between climate and health, they can empower communities to understand that climate change is not a distant environmental issue, it is a present and growing public health concern. Learn more about this initiative here.

Stay Connected with Dr. Madad:

Instagram

Twitter/X

LinkedIn

Facebook

More from Dr. Madad on the Academy Blog

Dr. Madad’s Critical Health Voices on Substack