While Aleksandr Nikitin has been temporarily acquitted on espionage charges, a higher court has appealed the case.

Published April 17, 2000

By Merle Spiegel

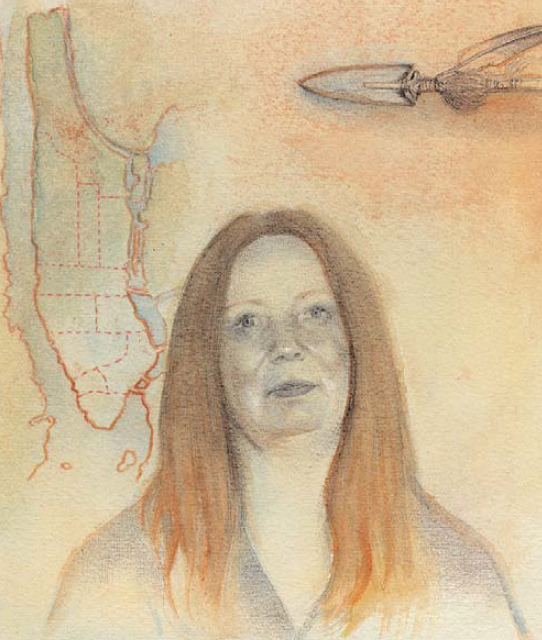

Nikitin says it was his wife, Tatyana, who made sure the world didn’t forget about him.

Tatyana Tchernova tried to maintain some human contact with the unannounced visitors. She offered them something to eat. It was the middle of the night, October 5, 1995, in her tiny apartment in St. Petersburg. The men were from the FSB, the Russian secret police, and were trying to find evidence that would put her husband, Aleksandr Nikitin, in jail or even have him executed.

That same morning Aleksandr Nikitin had returned from Moscow having learned that he would be issued visas from the Canadian embassy. Those visas would have allowed him to take his family to Toronto and start a new life. There had started to be friction between what he did for a living, his conscience, and his country.

Nikitin’s line of work was nuclear energy. Specifically, he knew about nuclear reactors on military submarines. He had been chief mechanic on a nuclear submarine in the Russian navy, and then a senior safety inspector. When Nikitin began talking about the danger of nuclear accidents in the northern fleet of submarines publicly expressing concerns about the future of 100 decommissioned vessels afloat in the North Sea and the growing threat presented by nuclear waste in the area, some began to see him as a threat. When he collaborated with the Norwegian environmental organization Bellona to tell the story and to ask for help from the international community in containing the environmental hazard, the FSB came to visit.

Psychological Warfare

Nikitin was charged repeatedly with treason and with revealing state secrets. He spent 10 months in prison. “The first two months,” he says, “was an attempt to destroy me psychologically.” He and his family were harassed repeatedly. They were followed. Their tires were slashed. He was indicted eight times and tried twice, each trial leading to neither conviction nor acquittal. The prosecution was told to keep trying. “Prosecution turned into persecution on a human level,” says Irwin Cotler, a Montreal-based lawyer who has followed the case.

On December 29, 1999, Nikitin was acquitted on all charges by the St. Petersburg City Court. He barely had time to celebrate before the prosecution appealed the decision to the Russian Supreme Court. Nevertheless, observers hope that this last verdict will permanently deflate the prosecution’s case, and the verdict was celebrated as a major victory by The New York Academy of Sciences and by human rights and environmental organizations around the world.

The most dangerous point in Nikitin’s journey was probably those early days before the world had heard of his case – while he was still just one man against a machine rooted in Soviet-era police tactics. Nikitin says it was his wife, Tatyana, who made sure the world didn’t forget about him. “She was constantly doing something,” he says. “She made phone calls and found people everywhere. All the people who are standing by me now, she got them involved in my case.”

The Academy Fights for Nikitin’s Release

On April 17, 2000, Nikitin won the final victory in the four-year nightmarish espionage case against him. The Russian Supreme Court confirmed the December 1999 judgment of the St. Petersburg City Court to dismiss all charges against Nikitin. Although the prosecution has a year in which it can appeal the decision, in all likelihood this judgement brings Nikitin’s ordeal to a happy conclusion.

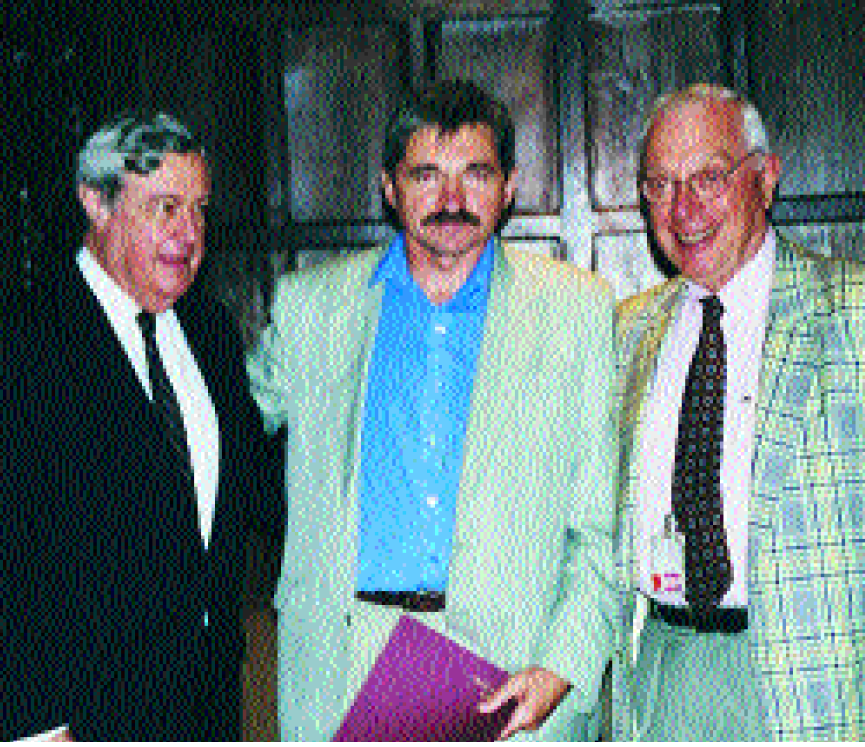

Working with The Bellona Foundation, the Sierra Club, and Amnesty International, the Academy mounted an intense lobbying effort in Washington, D.C. In addition, John Gillespie, Professor and Chair of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Lehman College, City University of New York, and a member of the Academy’s Human Rights Committee, spent time in St. Petersburg as an observer during the trial.

This case was the result of Nikitin’s contributions to the Bellona report entitled “The Russian Northern Fleet: Sources of Radioactive Contamination.” The report described the dangers associated with Russia’s nuclear-powered vessels, the storage of spent nuclear fuel, and other radioactive waste generated by the vessels.

“There was no crime.”

For his efforts to expose this environmental threat to the Russian public, Nikitin was accused of espionage by the FSB, the successor to the Soviet-era KGB. He was imprisoned for several months and repeatedly placed on trial during the past four years. Nikitin consistently maintained that all information he contributed to the report was publicly available and that the world community needed to know about the dangerous storage practices of nuclear waste in the Russian navy. Therefore, he stated, such information could not be classified as secret under the Russian Constitution. This latest trial involved the eighth set of charges made against Nikitin since 1996.

“Of course there was no crime,” Nikitin explained. “The Bellona report just describes one of the main environmental challenges for Russia. Information about nuclear hazards, waste, and accidents onboard nuclear submarines is no threat to national security. It is the nuclear problems that constitute a threat to Russia.”

Speaking after the Supreme Court ruling, Nikitin said a lot of work needs to be done to turn this personal victory into one for the country.

“I’ll continue to work with my colleagues at Bellona and to work for safe handling of the radioactive waste stored in the Murmansk area. We also have to work to support other environmentalists in Russia who are facing FSB trouble-makers,” he said.

Nikitin is the director of Bellona St. Petersburg, one of the international affiliates of the Bellona Foundation. He also heads the Environmental Rights Center, an organization that protects the legal rights of citizens to due process and legal protection in environmental cases.

Also read: Academy Aids Effort to Release Political Prisoner