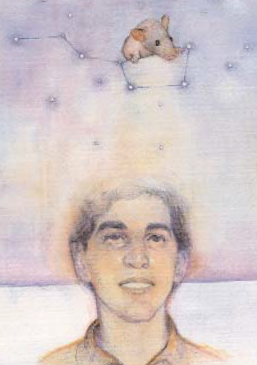

Since 1979 the Academy has offered impactful science training programs for students like Neeraj Singh who had the opportunity to study the swimming abilities of rats.

Published March 1, 2000

By Fred Moreno, Anne de León, and Jennifer Tang

No, “Rats in Space” is not the name of a new science fiction movie, although it may be a title with real potential for a budding Stephen Spielberg somewhere.

It’s actually the shortened name for a project by high school student Neeraj Singh that he developed through The New York Academy of Sciences’ (the Academy’s) Science Research Training Program. Begun in 1979, the eight-week program provides high school students throughout the greater NYC area with internships and real-world experiences.

To date, over 1650 students have worked with nearly 400 mentors from academic, industrial, and governmental science institutions who are willing to share their expertise with students like Neeraj. During the summer, Neeraj worked with Kerry Walton, PhD, one of the principal investigators involved in the 1998 Neurolab research mission in which scientists analyzed the brains and nervous systems of baby rats who spent 16 days aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia.

Neeraj learned how to interpret experimental designs, analyze data, consider a wide range of variables, and present scientific papers. He attended workshops at the Academy on science writing and science careers and gave an oral presentation of his work at a symposium that emulates a large-scale science conference.

Preparing for a Life in the Sciences

“The program offered me an interactive environment that a regular high school science class doesn’t,” he says. “I learned that the most challenging part of research is not the experimentation itself, but the analysis of data that follows.”

Studying rats’ swimming abilities revealed how their nervous system was affected since “they don’t use their bones and muscles much while swimming.” He notes that when first placed in the water, the flight rats reacted by swimming with coordinated strokes in less time than the ground control rats did. The controls reacted by floating and rotating their bodies instead. Through digital analysis, he also found that the hind limbs of the space flight rats moved differently while swimming. His conclusion? “Animals do not have pre-programmed motor capabilities and adapt their motor skills to their surrounding environment.”

Neeraj presented his findings at the annual Science and Technology Expo, sponsored by the Academy and the New York City Board of Education. With programs like these for students like Neeraj, the Academy plays a significant role in helping thousands of students prepare for, and pursue, a life in the sciences.

Learn more about educational opportunities at the Academy.