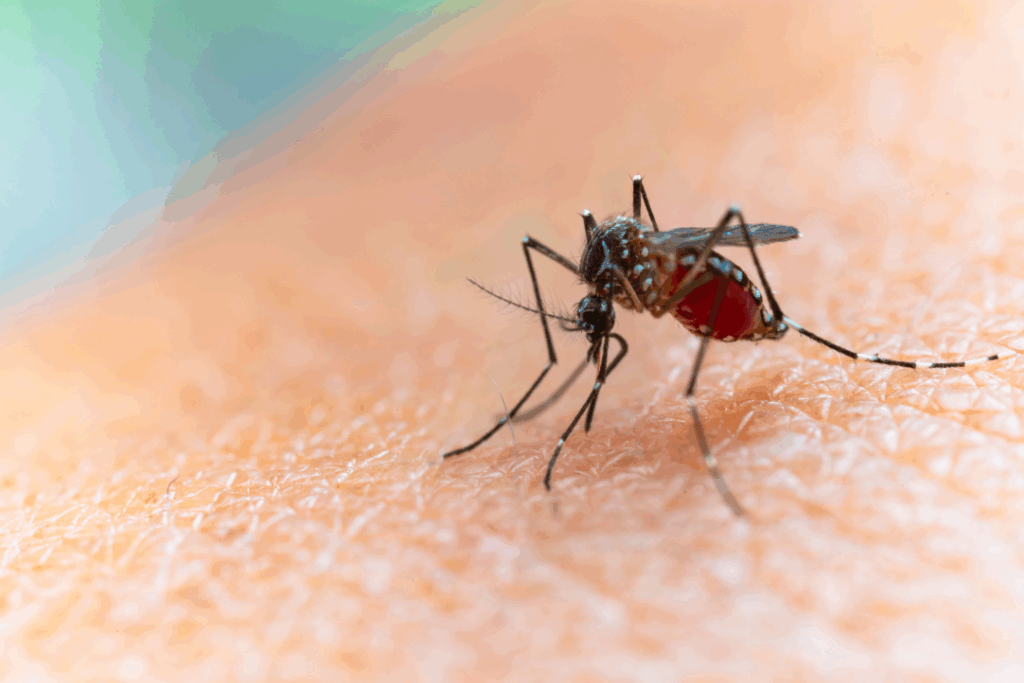

Mosquito habitats are rapidly expanding in the United States due to climate and environmental changes, exotic species, and urbanization. This raises new concerns about malaria’s re-emergence.

Published November 24, 2025

The United States is experiencing a swift expansion of mosquito habitats. Contributing factors include; invasive species, urbanization, climate change, and man-made changes to the environment. Warmer weather, shifting rainfall patterns, and less severe winters allow the Anopheles mosquito to breed and live in more places, and for longer periods of time. This problem becomes more serious as cities expand.

Because mosquito larvae thrive in standing water, which can be found in plenty in urban areas near construction sites, stormwater systems, and containers, mosquitoes are able to plague even the most densely populated urban areas. Another concerning issue is the discovery of a new invasive urban-adapted malaria vector, Anopheles stephensi, in the U.S. Their ability to survive in artificial water sources raises the risk of malaria transmission in previously low-risk areas.

Recent U.S. Malaria Cases Signal a Changing Landscape

In the summer of 2023, there were reports of ten cases of malaria that were locally acquired in the U.S. These were the first cases like this in 20 years and the largest cluster in 35 years. Seven of them happened in Sarasota County, and Florida, indicating focal transmission by local Anopheles mosquitoes. The last three cases were found in Texas, Maryland, and Arkansas. This shows that transmission can happen in places that are far apart when the right conditions are met.

The U.S. records about 2,000 cases of malaria each year, mostly among international travelers and recent immigrants from areas where the disease is common. The ten states that have been hit the hardest are New York, Maryland, California, Texas, New Jersey, Georgia, Virginia, Florida, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. The risk of local spread is higher in the summer because more people travel internationally, which is when mosquitoes are most common.

A Changing Climate Reshapes Disease Risk

Climate change makes the planet warmer and changes ecosystems. These changes affect how mosquitoes reproduce, live, and spread diseases. Since 1951, malaria has been eradicated in the United States. But because of rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns, competent mosquito vectors now have improved chances to thrive. Recent reports of malaria cases in the United States that were acquired locally remind us that getting rid of the disease doesn’t mean we will be safe from it in the future.

Why Temperature Matters for Malaria Transmission

Mosquitoes need warm places to breed. As temperatures rise, Anopheles mosquitoes, which are the main carriers of malaria, can now live in more parts of the country. In the U.S., the number of days with conditions favorable for mosquito activity has increased over the years by an average of 16 days. These changes let mosquitoes live in places that were once too cold for their entire life cycle, which raises the risk of malaria. The Plasmodium parasite needs heat to grow during the mosquito stage of its life cycle. Even small increases in temperature can speed up the growth of parasites in mosquitoes, increasing the likelihood of transmission.

Could Malaria Re-Establish in the U.S.?

In the U.S., malaria can still be spread by mosquitoes, especially when cases brought in from other countries are met with favorable environmental conditions. For re-establishment to happen, there must be three things: competent mosquito vectors, favorable climate, and people who are infected with malaria. The U.S. has strong protective systems, such as constant monitoring, quick case detection, vector control programs, and easy access to healthcare. These systems make it less likely that the country will become a malaria-endemic country. But even with these protections, it’s still important to be careful. To stop a resurgence, there needs to be sustained surveillance and rapid public health action.

Climate Change Makes Global Health Everyone’s Business

Changes in climate are changing how diseases spread around the world. Health risks that used to be limited to tropical areas are now spreading to new places. This change impacts how countries, communities, and people must get ready. The U.S. can’t ignore the signs that malaria might come back, even though it probably won’t come back as bad as it did a hundred years ago. Warmer weather, mosquitoes spreading to new areas, and occasional local cases show that we still need to be careful. Acting on climate change protects public health, ecosystems, and infrastructure. Taking climate change seriously is important for many reasons, including protecting communities from diseases spread by mosquitoes.

Also read: New Insight into the Evolutionary History of Urban Mosquitoes