The components that were state-of-the-art two years ago are now obsolete in today’s world.

Published May 1, 2018

By Charles Cooper

In the decade following the debut of the first iPhone in 2007, Apple has released 18 different models of its iconic smartphone, some major, some minor — all designed with the idea of appealing to buyers thirsting for the latest and the greatest technology from Silicon Valley’s most iconic brand.

That’s the way our gadget-addicted economy works. Products rarely remain in their original owners’ hands for longer than a few years. Planned obsolescence is the rule as slick marketing campaigns encourage consumers to trade up to faster, cheaper and smaller devices that roll off assembly lines, because yesterday’s state-of-the-art technology won’t hold a candle to what’s coming tomorrow.

“The problem we run into in the IT industry is profound because the functionality of these devices advances so quickly,” said Dr. Matthew Realff, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “The components that were state-of-the-art two years ago are now obsolete in today’s world. This is not a technological problem but a societal one. Replacing your phones every six months or every year or two, may not, from a sustainability perspective, be needed. The problem is that the industry wants to drive functionality at every step.”

So as digitization transforms how society communicates and does business, there are now billions of smartphones, personal computers and connected devices in use worldwide. But what happens when these and other high-tech appliances — televisions, printers, scanners, fax machines and other technology peripherals — reach the end of their useful lives? That darker side of the digital revolution is having a major impact on the lives of millions of people and their environment every day.

The Fastest-Growing Stream of Municipal Solid Waste

Electronic waste (e-waste) now constitutes the fastest-growing stream of municipal solid waste in the world, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. People now generate some 40 million tons of e-waste each year — up 20 percent in just two years, leading the United Nations to warn of a veritable “tsunami of e-waste” inundating the Earth.

The toxic threat to health is so severe that scientists warn of a global safety threat linked to the release of harmful substances such as lead, mercury, cadmium and arsenic, in discarded electrical devices and equipment. The implications are particularly acute for developing nations where older products often get dumped in landfills. As more e-waste winds up in landfills, the exposure to environmental toxins creates health hazards for workers and residents, including greater risks of cancer and neurological disorders.

Alarm over the public health challenge has forced the issue onto the global agenda. In fact, one of the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals (#12) is a pledge to “substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse” by 2030. The success of that initiative will be closely intertwined with progress made battling e-waste.

Given the magnitude of the challenge, it’s too early to handicap the outcome. Experts in the field are guardedly optimistic, saying it will take a combination of smart engineering and equally smart public policies to help reverse a years-in-the-making problem paradoxically created by the very technology used to solve so many other societal problems.

Don’t Expect A Quick Fix

“Originally, you had a paradigm in which these products were never considered from an end-of-life cycle perspective,” said Nancy Gillis, Chief Executive Officer of the Green Electronics Council. “In fact, the IT sector was treated no differently from any other products in our consumer society. So when people asked the question, `What do we do with this stuff later on?’ the response was `We know … we’ll stick it all in a hole.’ Then we became aware of the fact that we don’t have enough holes. They’re not big enough and they’re costing us.”

Compounding the challenge, she said, is the incessant churn of new technology into the market. Projections vary, but tens of billions of IoT devices will be online by the end of this decade.

“When you start putting sensors in your shirts and shoes or when toys become as much IT as IT is considered, then we’re ill prepared for that also becoming part of the [e-waste] stream,” Gillis added. “It’d be great if technology just evolved along the same timeline as our understanding of its impact … we wouldn’t have a problem. But it’s not. This is a development cycle made up of many players and it involves an extremely complex supply chain.”

High-Tech Alternatives in Flux

Realff has thought a lot about how supply chain management could make a difference in controlling e-waste. One area where he sees potential is in the application of advanced computational methods, such as machine learning and mathematical programming to improve product tracking as materials flow through supply chains. By adding smart tags to products, companies will soon be able to wirelessly track items flowing through supply chains to customers to get a comprehensive picture.

“We’re getting to the point where our ability to label individual items and keep track of them is about to increase exponentially,” he said. “With the availability of inexpensive embedded sensors and ubiquitous wireless networks, we’ll know how long they are in use and when they eventually get retired.”

Big Data and the Internet of Things

As these and other technologies, including Big Data and IoT improve supply chain visibility, it should also clear the way for companies to do a better job retrieving value from discarded e-waste. There’s money to be made cleaning up e-waste as many products contain valuable materials — including gold, silver, copper and palladium — that can be resold. The International Telecommunication Union put the estimated value of recoverable material generated by e-waste in 2016 at $55 billion.

However, only 20 percent of that e-waste was found to have been collected and recycled despite the presence of those high-value recoverable materials. In other cases, perfectly fine machines still capable of productive service are getting discarded. That’s where better analytical insights into the data can give them a second life.

“We need to figure out how to reuse those systems in ways in which they benefit the less fortunate parts of the world,” said Realff. “We may not need top-of-the-line servers to do certain tasks, but how do we take servers that may not be used in a Google warehouse and use them where they could still have value? It’s less a technology issue, than an organizational issue.”

The Emergence of Nanotechnology and Synthetic Biology

From a sustainable development goal perspective, nanotechnology and synthetic biology are two emerging fields of science and technology that have attracted interest due to their broad applicability and their potential as alternative solutions.

Bart Kolodziejczyk, co-author of a recent paper on recycling standards to handle nanowaste, pointed to the history of polymers and plastic, which were originally hailed as game-changing developments. But they also led to unintended consequences.

“Not only are we surrounded by plastic waste that take decades to decompose in the environment, but only recently have we reached the point when the very first plastic waste finally starts degrading,” he said. “While we should be happy, there is another problem … the degradation of polymeric materials is incomplete; partially degraded plastic nanoparticles can be currently found in 83 percent of the world’s tap water, including most U.S. cities. You can imagine that these plastic fibers are not good for your health, cannot be easily digested and build up in your body.”

Similarly, he said there are still unanswered safety questions around nanowaste and synthetic biology waste.

“We certainly don’t know how to deal with hazards associated with these two very promising technologies. I am even more skeptical when I attend different workshops and conferences organized by international organizations because policy makers simply don’t know how to deal with this type of a threat.”

“Nanowaste disposal will be a big issue because different nanoparticles will require different and tailored waste treatment protocols,” Kolodziejczyk added. “While most organic nanoparticles, such as polymers, can be potentially digested by flame, inorganic nanoparticles, such as oxides known for high thermal stability will require more sophisticated methods.”

Reasons for Optimism

Despite the clear challenges, Gillis says that growing recognition of the e-waste problem is reason enough for optimism that things can improve.

“We’re starting to think seriously about end of life while designing products and there’s also a recognition that there’s money involved in getting those core resources back,” she said. “Companies are leaving money on the table which is foolish.”

As we wait for market forces and new technologies to come to the rescue, the easiest way to reduce the amount of e-waste would be for people and businesses to resist the urge to discard perfectly usable older products just because a newer, more robust version hit the market.

But is it reasonable to expect users to resist the siren call of advertising and change age-old consumption patterns? Maybe that’s asking for too much. For Realff, however, it’s a question that needs to get asked — if only to avoid the inevitable consequences of continuing along the current path.

“Maybe we can’t all have the latest and greatest,” he said. “And I’m not just referring to consumers here in the West but also to the billions of consumers in the rest of the world. We will not be talking about tsunamis of e-waste; we will be talking about a planet full of e-waste — which obviously is not feasible.”

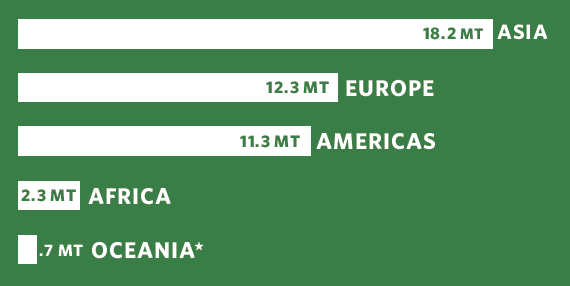

Who Generates the Most E-Waste?

According to The Global E-waste Monitor 2017, a publication produced by the Global E-waste Statistics Partnership, Asia takes the lead followed by Europe and the Americas.

The Global E-waste Partnership is a collaborative effort of the United Nations University (UNU), represented through its Vice-Rectorate in Europe hosted Sustainable Cycles (SCYCLE) Programme, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and the International Solid Waste Association (ISWA).

Also see:

Charles Cooper is a Silicon-valley based technology writer and former Executive Editor of CNET.