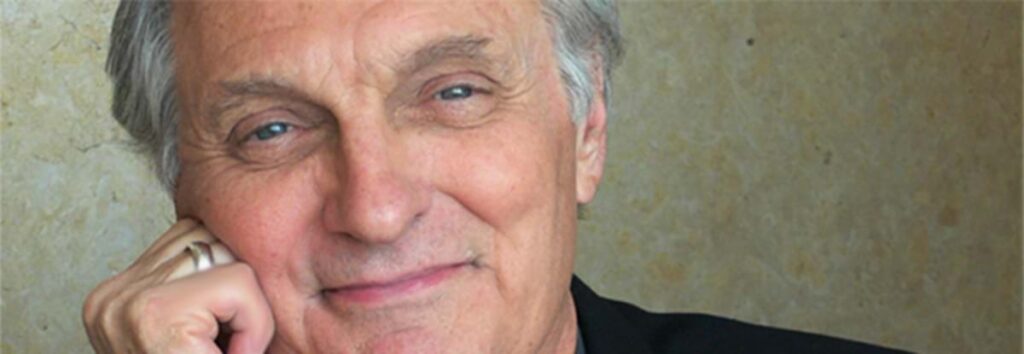

Actor and science advocate Alan Alda discusses his passion for communication — in science, in theater, and in life.

Published November 03, 2014

By Diana Friedman

Starring Alan Alda & Candice Bergen

November 9 — December 5

Use Offer Code: LIFE

lovelettersbroadway.com

Alan Alda gets uncomfortable making small talk at parties, but he is passionate about authentic, effective communication. Especially where science is concerned.

An actor, writer, and director whom many know from his Emmy Award-winning roles in The West Wing and M*A*S*H and as recurring frenemy Alan Fitch on NBC’s The Blacklist, Alda is also a lifelong science enthusiast who has spent the last 20+ years advocating for the understanding and clear communication of science. For 11 years he interviewed scientists as host of Scientific American Frontiers.

He has received numerous communications and service awards, including the National Science Board’s Public Service Award (2006) and the AAAS Kavli Science Journalism Award for The Human Spark (2010). His interest in using improvisation techniques to train scientists to communicate more effectively inspired the founding of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University, where he is a Visiting Professor.

Starting November 9, Alda stars with Candice Bergen in Love Letters at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre in New York, part of a rotating cast of two characters communicating through letters and notes written over five decades. He spoke recently with the Academy about how scientists can better convey their message, the importance of empathy, and his passion for making a connection. An excerpt from this interview follows.

Academy

I find it interesting that you’re returning to Broadway in a play that is fundamentally about making connections through communication. How do you think Love Letters fits into your larger body of work, especially now that you’ve become as much associated with communicating science through arts and entertainment media as for arts and entertainment media itself?

Alda

That’s a really interesting question, because I really do think that there are fundamental things about communication that affect the communication of science and the communication between lovers, between friends and enemies, among all people. That is the basis of what we put scientists through at the Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook, which is to have a series of experiences in which you can become comfortable “reading” the mind of the person you’re working with.

The theory of mind idea. Essentially, empathy. It means that you can tell — by the clues you’re getting, by signals you’re getting — how the person is understanding what you’re saying. That’s important whether you’re communicating science or writing a love letter or responding to a love letter. If it’s as plain as the nose on your face that the person isn’t following what you’re saying, and you ignore that and are more concerned with what you have to say than how it’s being received, then you’re in trouble. Both in love and in science.

Academy

You’ve concentrated a lot on communication for scientists. Why would scientists in particular benefit from improv and communications training?

“You have emotion trained out of you when you’re writing science. But people rely on story and emotion.”

Alda

The improv games and exercises that we do are all aimed at a particular thing, which is to become habituated in reading signals from the other person. To really see the other person. So that when you turn to an audience — either a real audience in an auditorium or a virtual audience at the other end of your keypad — you’re ready to think about what they’re thinking as you communicate step-by-step with them. These improv exercises are not designed to make you quick on your feet or funny — although you are more comfortable and can be more yourself. That’s one of the big advantages, that the real “you” comes out. But the first thing we’re aiming for is for you to be connected with the people you’re trying to communicate with.

Academy

Promotion, selling, public speaking: they’re all as important in science as in acting, but many actors and many scientists both shy away from it. How do you motivate scientists beyond the communication techniques to tackling that reluctance?

Alda

Well, once you see how enjoyable it is, you want to do it. What’s enjoyable is the human contact. We often shrink from human contact because we feel naked out there sometimes. I mean, I’m not comfortable with cocktail parties.

I have to use what I’ve learned in communication to be comfortable, to realize that the person I’m talking to has probably the same uncertainty about the situation that I do. [But] if I pay attention to what they’re saying, if I ask them almost anything and listen to what they answer, we have a conversation, and it can get deeper and deeper and more interesting. I wind up talking for half an hour to the first person I bump into because they become instantly fascinating — if you make contact.

But if you stick to the weather and how long are you in town for — questions that don’t really require any connection — you don’t get anywhere. Last night at dinner I was sitting next to somebody I didn’t know, and I asked her what her passion was. And, boom, we went on for a half an hour.

Academy

It sounds like you’re less comfortable in the cocktail party than you are onstage.

Alda

Well, onstage you’re protected. If you’re doing a play, you have something that you’ve rehearsed, and you know what to expect. But, still, you can’t achieve what you’re going onstage for unless you can make real contact with the fellow players. That’s the essence of what we’ve found about communication: that connection, that awareness of the other person, immediately relaxes you. When you address the audience directly, they become your fellow players. And there’s a big difference between thinking of them as your fellow players and thinking of them as people who are judging you.

So you’re immediately more relaxed and more who you really are, and they respond to that. This was really clear to me when I was doing Scientific American Frontiers. In most interviews you already know the answer to the questions. I didn’t know what the questions were; I didn’t know what the answers were. I just wanted to understand what their work was. And if I didn’t understand it, I’d badger them until I did.

They lost all interest in talking to the camera and really wanted me, personally, to understand it. It was just me and them. Their humor came out, their curiosity. It was an intimate interaction. That’s what we want and what we work hard to get scientists to do when they communicate. We invite them to tell stories, to let themselves be in the stories. Because that’s what audiences will respond to.

You have emotion trained out of you when you’re writing science for other scientists in your field. But people like me, ordinary people, rely on story and emotion. A story of how you overcame obstacles to achieve this thing in science that you’ve achieved. We don’t want to hear the end of it first. We want to hear the story like a detective story.

Academy

Then if a reader could take away just one thing from this conversation and put it into action that day, what would it be?

“There has to be a human connection for us to listen, even when you’re talking to other scientists.”

Alda

The thing is to connect with the people you’re talking to or writing for. What are they thinking when you say the first thing you’re saying? Who are they? What do they know already? That old thing of knowing your audience — it’s not just knowing your audience; it’s connecting to your audience. To be there with them in the same room. I’ve had so many young scientists say “I overcome my fear by looking over the heads of the audience.”

[But] once you get used to the fact that they’re your playmates and not your adversaries, you overcome your fear by looking them in the eye. By enjoying their company. Then you actually can develop — it seems hard to believe — but you actually can develop a personal relationship with a group of strangers.

Even though scientists are talking about extremely rigorous subject matter, they can be just as spontaneous about the way they talk about it. If they’re not spontaneous, or if they commit that horrible sin of reading their PowerPoint deck. It’s very hard to listen to that. It’s hard to process it. It’s hard to understand it, and it’s very hard to remember it. There has to be a human connection for us to listen, and this is even when you’re talking to other scientists.

You get a little leeway if they’re exactly in your field. But sometimes not even then. I’ve heard this from mathematicians, that they can’t understand one another frequently because of special terms they use. When the Obama BRAIN Initiative was begun, the team that first met about that — before he announced the initiative — was made up of nanoscientists and neuroscientists. They spent hours wasting time because they didn’t agree on what the definition of “probe” was.

A simple thing like the use of a word can get you in trouble. But other kinds of shorthand can, and piling one concept on top of another before you really are sure that they know what you’re talking about. You can lose them so badly. You’ve got to be tracking what they’re thinking.

Academy

If scientists have such difficulty talking to each other in a common language, how do you think they can — “translate” feels like the wrong word, but — translate it for an audience completely outside themselves?

Alda

Well, that’s what we do. They have to get outside the curse of knowledge. When we train them, we put them through a process that we call “distilling your message” where we show them how hard it is to understand something that is written with inside language. First we let them try to figure out the inside language of something that has nothing to do with science, to see how difficult it is to listen to something you don’t know the terms for. It’s a very enjoyable and challenging process, and they leave it able to use everyday terms for complex things, the way [Richard] Feynman was so good at.

Academy

One last question: What’s your passion?

Alda

[laughs] I have a lot of passions. I don’t know if I could boil it down to one. I really think of acting as a kind of ecstasy. It makes me really happy when I can take off — and for days, I can have the pleasure that I had in that moment when it took off, and was unexpected, and I was swimming in the tank with the other actor.

But it’s almost the same feeling when I can see somebody I’m working with, helping them communicate better. When I see them take off and open up and become themselves in front of other people, or write in a way that has so much more clarity and vividness than it had before, it really makes me happy. They’re almost the same passion.

I was thinking of a scene I did with [James Spader] the day before yesterday. Two days ago I did it, and this morning I was thinking, Boy, that was really fun. It’s a wonderful feeling, of having got somewhere. And it doesn’t have anything to do with success or notoriety. It’s probably what some explorer feels when he finds an ocean nobody’s seen before. You just get really happy inside.

Academy

For making that connection?

Alda

Yeah. I love to see the scientists make that connection and feel that joy.