Overview

The Blavatnik Awards for Young Scientists in the United Kingdom are the largest unrestricted prize available to early career scientists in the Life Sciences, Physical Sciences & Engineering, and Chemistry in the UK. The three 2021 Laureates each received £100,000, and two Finalists in each category received £30,000 per person. The honorees are recognized for their research, which pushes the boundaries of our current technology and understanding of the world. In this event, held at the historic Banqueting House in London, the UK Laureates and Finalists had a chance to explain their work and its ramifications to the public.

Victoria Gill, a Science and Environment Correspondent for the BBC, introduced and moderated the event. She noted that “Science has saved the world and will continue to do so,” and stressed how important it is for scientists to engage the public and share their discoveries at events like this. This theme arose over and over again over the course of the day.

Symposium Highlights

- Single-cell analyses can reveal how multicellular animals develop and how our immune systems deal with different pathogens we encounter over the course of our lives.

- Viruses that attack bacteria—bacteriophages—may help us fight antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens.

- Fossils offer us a glimpse into what life on Earth was like for the millennia in which it thrived before mammals took over.

- Stacking layers of single-atom-thick sheets can make new materials with desired, customizable properties.

- Memristors are electronic components that can remember a variety of memory states, and can be used to build quicker and more versatile computer chips than currently used.

- The detection of the Higgs boson, which had been posited for decades by mathematical theory but was very difficult to detect, confirmed the Standard Model of Physics.

- Single molecule magnets can be utilized for high density data storage—if they can retain their magnetism at high enough temperatures.

- When examining how life first arose on Earth, we must consider all of its requisite components and reactions in aggregate rather than assigning primacy to any one of them.

Speakers

Stephen L. Brusatte

The University of Edinburgh

Sinéad Farrington

The University of Edinburgh

John Marioni

European Bioinformatics Institute and University of Cambridge

David P. Mills

The University of Manchester

Artem Mishchenko

The University of Manchester

Matthew Powner

University College London

Themis Prodromakis

University of Southampton

Edze Westra

University of Exeter

Innovating in Life Sciences

Speakers

John Marioni, PhD

European Bioinformatics Institute and University of Cambridge, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Life Sciences Finalist

Edze Westra, PhD

University of Exeter, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Life Sciences Finalist

Stephen Brusatte, PhD

The University of Edinburgh, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Life Sciences Laureate

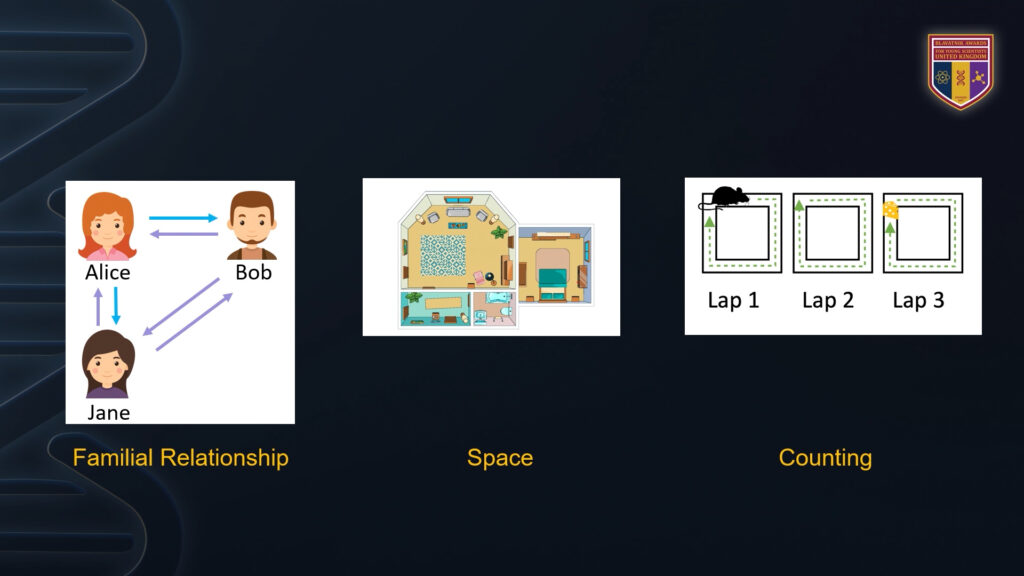

How to Build an Animal

John Marioni, PhD, European Bioinformatics Institute and University of Cambridge, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Life Sciences Finalist

Animals grow from one single cell: a fertilized egg. During development, that cell splits into two, and then into four, and so on, creating an embryo that grows into the billions of cells comprising a whole animal. Along the way, the cells must differentiate into all of the different cell types necessary to create every aspect of that animal.

Each cell follows its own path to arrive at its eventual fate. Traditionally, the decisions each cell has to make along that path have been studied using large groups of cells or tissues; this is because scientific lab techniques have typically required a substantial amount of starting material to perform analyses. But now, thanks in large part to the discoveries of John Marioni and his lab group, we have the technology to track individual cells as they mature into different cell types.

Marioni has created analytical methods capable of observing patterns in all of the genes expressed by individual cells. Importantly, these computational and statistical methods can be used to analyze the enormous amounts of data generated from the gene expression patterns of many individual cells simultaneously. In addition to furthering our understanding of cell fate decisions in embryonic development, this area of research—single cell genomics—can also be applied to many other processes in the body.

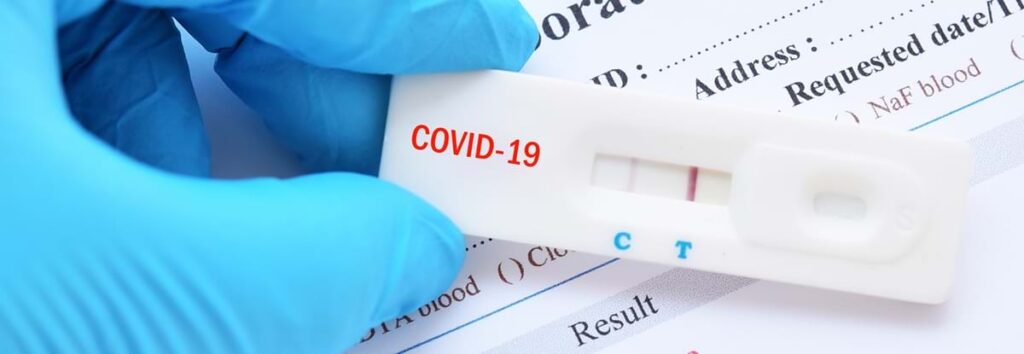

One relevant application is to the immune system: single cell genomics can detect immune cell types that are activated by exposure to a particular pathogen. To illustrate this, Marioni showed many gorgeous, colorized images of individual cells, highlighting their unique morphology and function. Included in these images was histology showing profiles of different types of T cells elicited by infection with SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19).

The cells were computationally grouped by genetic profile and graphed to show how the different cell types correlated with disease severity. There are many other clinical applications of his research into genomics. For instance, he said, if we know exactly which cell types in the body express the targets of specific drugs, we will be better able to predict that drug’s effects (and side effects).

In addition to his lab work, Marioni is involved in the Human Cell Atlas initiative, a global collaborative project whose goal it is to genetically map all of the cell types in healthy human adults. When a cell uses a particular gene, it is said to “transcribe” that gene to make a particular protein—thus, the catalog of all of the genes one cell uses is called its “transcriptome.” The Human Cell Atlas is using these single cell transcriptomes to create the whole genetic map.

This research is currently completely redefining how we think of cell types by transforming our definition of a “cell” from the way it looks to the genetic profile.

Bacteria and Their Viruses: A Microbial Arms Race

Edze Westra, PhD University of Exeter, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Life Sciences Finalist

All organisms have viruses that target them for infection; bacteria are no exception. The viruses that infect bacteria are called bacteriophages, or phages.

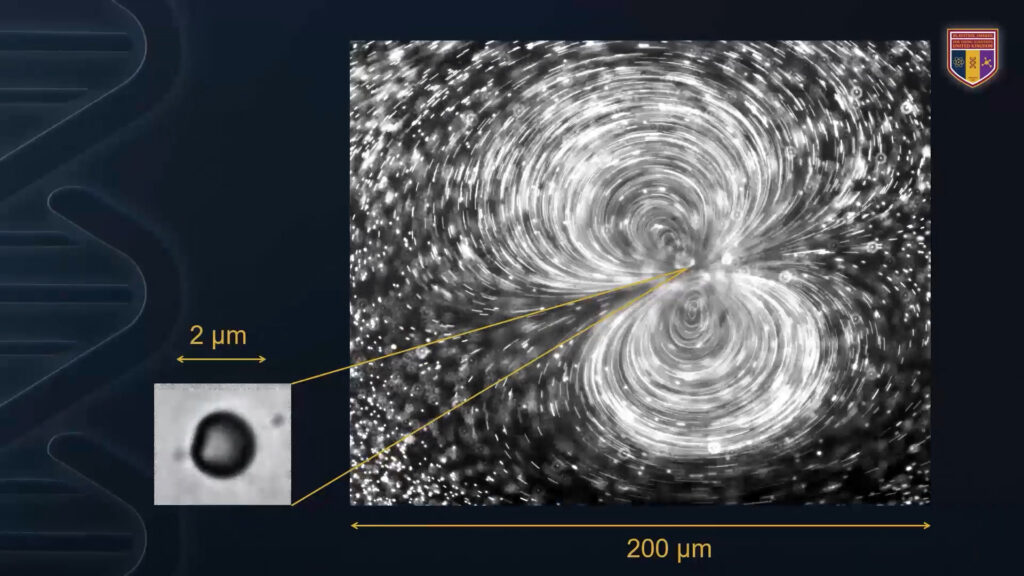

Edze Westra’s lab studies how bacteria evolve to defend themselves against infection by phage and, specifically, how elements of their environment drive the evolution of their immune systems. Like humans, bacteria have two main types of immune systems: an innate immune system and an adaptive immune system. The innate immune system works similarly in both bacteria and humans by modifying molecules on the cell surface so that the phage can’t gain entry to the cell.

In humans, the adaptive immune system is what creates antibodies. In bacteria, the adaptive immune system works a little bit differently—a gene editing system, called CRISPR-Cas, cuts out pieces of the phage’s genome and uses it as a template to identify all other phages of the same type. Using this method, the bacterial cell can quickly discover and neutralize any infectious phage by destroying the phage’s genetic material. In recent years, scientists have harnessed the CRISPR-Cas system for use in gene editing technology.

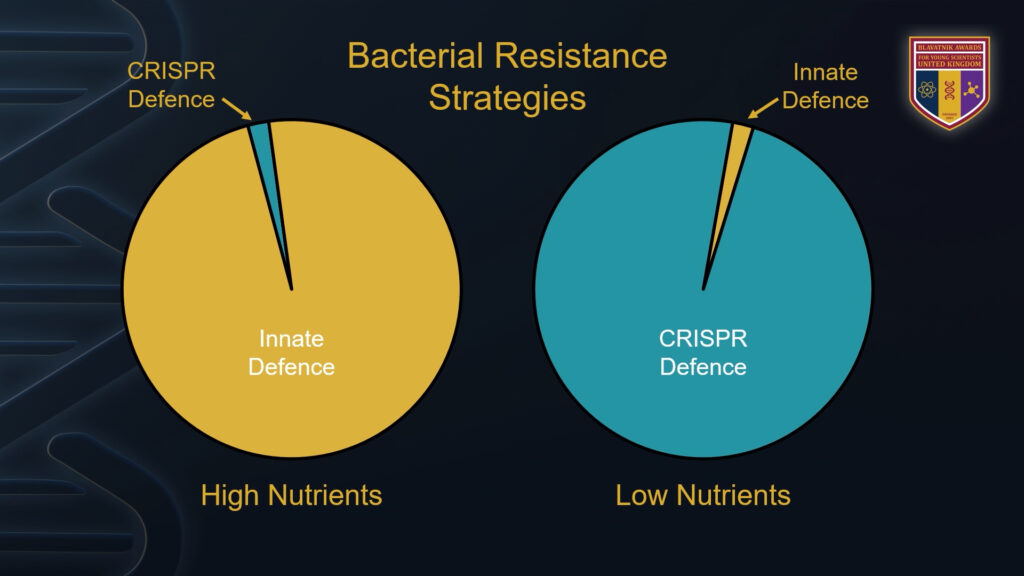

Westra wanted to know under what conditions do bacteria use their innate immune system versus their adaptive immune system: How do they decide?

In studies using the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa, his lab found that the decision to use adaptive vs. innate immunity is controlled almost exclusively by nutrient levels in the surrounding environment. When nutrient levels are low, the bacteria use the adaptive immune system, CRISPR-Cas; when nutrient levels are high, the bacteria rely on their innate immune system. He recognized that this means we can artificially guide the evolution of bacterial defense by controlling elements in their environment.

When we need to attack pathogenic bacteria for medical purposes, such as in a sick or infected patient, we turn to antibiotics. However, many strains of bacteria have developed resistance to antibiotics, leaving humans vulnerable to infection.

Additionally, our antibiotics tend to kill broad classes of microbes, often damaging the beneficial species we harbor in our bodies along with the pathogenic ones we are trying to eliminate. Phage therapy—a medical treatment where phages are administered to a patient with a severe bacterial infection—might be a good way to circumvent antibiotic resistance while also attacking bacteria in a more targeted manner, harming only those that harm us and leaving the others be.

Although it is difficult to manipulate bacterial nutrients within the context of a patient’s body, we can use antibiotics to direct this behavior. Antibiotics that are shown to limit bacterial growth will induce the bacteria to use the CRISPR-Cas strategy, mimicking the effects of a low-nutrient environment; antibiotics that work by killing bacteria will induce them to use their innate defenses. In this way, it may be possible to direct the evolution of bacterial defense systems in order to reveal their weaknesses and target them with phage therapy.

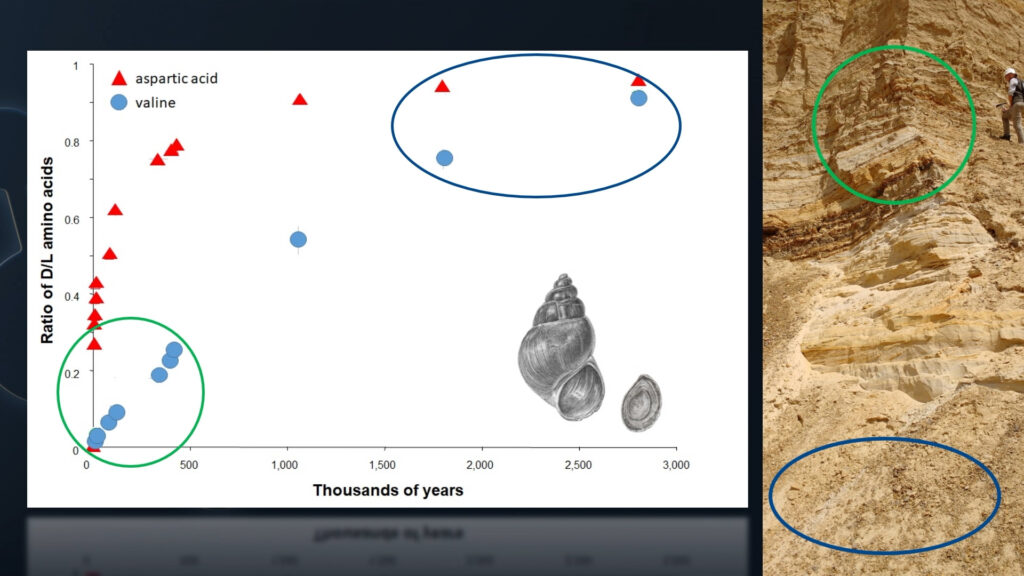

The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs

Stephen Brusatte, PhD The University of Edinburgh, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Life Sciences Laureate|

Stephen Brusatte is a paleontologist, “and paleontologists”, he says, “are really historians”. Just as historians study recorded history to learn about the past, paleontologists study prehistory for the same reasons.

The Earth is four and a half billion years old, and humans have only been around for the last three hundred and fifty thousand of those years. Dinosaurs were the largest living creatures to ever walk the earth; they started out around the size of house cats, and over eighty million years they evolved into the giant T. rexes, Stegosauruses, and Brontosauruses in our picture books.

They reigned until a six-mile-wide asteroid struck the Earth sixty-six million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period, extinguishing them along with seventy-five percent of the other species on the planet. Brusatte called this day “the worst day in Earth’s history.” However, the demise of dinosaurs paved the way for mammals to take over.

Fossils can tell us a lot about how life on this planet used to be, how the earth and its occupants respond to climate and environmental changes, and how evolution works over long timescales. Particularly, fossils show how entirely new species and body plans emerge.

Each fossil can yield new knowledge and new discoveries about a lost world, he said. It can teach us how bodies change and, ultimately, how evolution works. It is from fossils that we know that today’s birds evolved from dinosaurs.

Life Sciences Panel Discussion

Victoria Gill started the life sciences panel discussion by asking all three of the awardees if, and how, the COVID-19 pandemic changed their professional lives: did it alter their scientific approach or were they asking different questions?

Westra replied that the lab shutdown forced different, non-experimental approaches, notably bioinformatics on old sequence data. He said that they found mobile genetic elements, and the models of how they moved through a population reminded him of epidemiological models of COVID spread.

Marioni shared that he was inspired by how the international scientific community came together to solve the problem posed by the pandemic. Everyone shared samples and worked as a team, instead of working in isolation as they usually do. Brusatte agreed that enhanced collaboration accelerated discoveries and should be maintained.

Questions from the audience, both in person and online, covered a similarly broad of a range of topics. An audience member asked about where new cell types come from; Marioni explained that if we computationally look at gene transcription changes in single cells over time, we can make phylogenetic trees showing how cells with different expression patterns arise.

A digital attendee asked Brusatte why birds survived the asteroid impact when other dinosaurs didn’t. Brusatte replied that the answer is not clear, but it is probably due to a number of factors: they have beaks so they can eat seeds, they can fly, and they grow fast. Plus, he said, most birds actually did not survive beyond the asteroid impact.

Another audience member asked Brusatte if the theory that the asteroid killed the dinosaurs was widely accepted. He replied that it is widely accepted that the impact ended the Cretaceous period, but some scientists still argue that other factors, like volcanic eruptions in India, were the prime mover behind the dinosaurs’ demise.

Another viewer asked Westra why the environment impacts a bacterium’s immune strategy. He answered that in the presence of antibiotics that slow growth, infection and metabolism are likewise slowed so the bacteria simply have more time to respond. He added that the level of diversity in the attacking phage may also play a role, as innate immunity is better able to deal with multiple variants.

To wrap up the session, Victoria Gill asked about the importance of diversity and representation and wondered how to make awards programs like this more inclusive. All three scientists agreed that it is hugely important, that the lack of diversity is a problem across all fields of research, that all voices must be heard, and that the only way to change it is by having hard metrics to rank universities and departments on the demographics of their faculty.

Innovating in Physical Sciences & Engineering

Speakers

Artem Mishchenko, PhD

The University of Manchester, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Physical Sciences & Engineering Finalist

Themis Prodromakis, PhD

University of Southampton, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Physical Sciences & Engineering Finalist

Sinead Farrington, PhD

The University of Edinburgh, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Physical Sciences & Engineering Laureate

Programmable van der Waals Materials

Artem Mishchenko, PhD The University of Manchester, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Physical Sciences & Engineering Finalist

Materials science is vital because materials define what we can do, and thus define us. That’s why the different eras in prehistory are named for the materials used: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, the Iron Age, the Copper Age. The properties of the materials available dictated the technologies that could be developed then, and the properties of the materials available still dictate the technologies that can be developed now.

Van der Waals materials are materials that are only one or a few atoms thick. The most well-known is probably graphene, which was discovered in 2004 and is made of carbon. But now hundreds of these two-dimensional materials are available, representing almost the whole periodic table, and each has different properties. They are the cutting edge of materials innovation.

Mishchenko studies how van der Waals materials can be made and manipulated into materials with customizable, programmable properties. He does this by stacking the materials and rotating the layers relative to each other. Rotating the layers used to be painstaking, time-consuming work, requiring a new rig to make each new angle of rotation. But his lab developed a single device that can twist the layers by any amount he wants. He can thus much more easily make and assess the properties of each different material generated when he rotates a layer by a given angle, since he can then just reset his device to turn the layer more or less to devise a new material. Every degree of rotation confers new properties.

His lab has found that rotating the layers can tune the conductivity of the materials and that the right combination of angle and current can make a transistor that can generate radio waves suitable for high frequency telecommunications. With infinite combinations of layers available to make new materials, this new field of “twistronics” may generate an entirely new physics, with quantum properties and exciting possibilities for biomedicine and sustainability.

Memristive Technologies: From Nano Devices to AI on a Chip

Themis Prodromakis, PhD University of Southampton, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Physical Sciences & Engineering Finalist

Transistors are key elements in our electronic devices. They process and store information by switching between on and off states. Traditionally, in order to increase the speed and efficiency of a device one increased the number of transistors it contained. This usually entailed making them smaller. Smartphones contain seven billion transistors! But now it has become more and more difficult to further shrink the size of transistors.

Themis Prodromakis and his team have been instrumental in developing a new electronic component: the memristor, or memory resistor. Memristors are a new kind of switch; they can store hundreds of memory states, beyond on and off states, on a single, nanometer-scale device. Sending a voltage pulse across a device allows to tune the resistance of the memristor at distinct levels, and the device remembers them all.

One benefit of memristors is that they allow for more computational capacity while using much less energy from conventional circuit components. Systems made out of memristors allow us to embed intelligence everywhere by processing and storing big data locally, rather than in the cloud. And by removing the need to share data with the cloud, electronic devices made out of memristors can remain secure and private. Prodromakis has not only developed and tested memristors, he is also quite invested in realizing their practical applications and bringing them to market.

Another amazing application of memristors is linking neural networks to artificial ones. Prodromakis and his team have already successfully connected biological and artificial neurons together and enabled them to communicate over the internet using memristors as synapses. He speculates that such neuroprosthetic devices might one day be used to fix or even augment human capabilities, for example by replacing dysfunctional regions of the brain in Alzheimer’s patients. And if memristors can be embedded in a human body, they can be embedded in other environments previously inaccessible to electronics as well.

What Do We Know About the Higgs Boson?

Sinead Farrington, PhD The University of Edinburgh, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Physical Sciences & Engineering Laureate

In the Standard Model of particle physics, the bedrock of modern physics, fermions are the elementary particles comprising all of the stable matter in the universe, while bosons—the other collection of elementary particles—are the ones that transmit forces. The Higgs boson, whose existence was theoretically proposed in 1964, is a unique particle; it gives mass to the other particles by coupling with them.

Sinéad Farrington led the group at CERN that further elucidated the properties of the Higgs boson and thus bolstered the Standard Model. The Standard Model “effectively encapsulates a remarkably small set of particles that make up everything we know about and are able to create,” explained Farrington.

“The Higgs boson is needed to maintain the compelling self-consistency of the Standard Model. It was there in theory, but the experimental observation of it was a really big deal. Nature did not have to work out that way,” Farrington said.

Farrington and her 100-person international team at the Large Hadron Collider demonstrated that the Higgs boson spontaneously decays into two fermions called tau leptons. This was experimentally challenging because tau is unstable, so the group had to infer that it was there based on its own degradation products. She then went on to develop the analytical tools needed to further record and interpret the tau lepton data and was the first to use machine learning to trigger, record, and analyze the massive amounts of data generated by experiments at the LHC.

Now she is looking to discover other long-lived but as yet unknown particles beyond the Standard Model that also decay into tau leptons, and plans to make more measurements using the Large Hadron Collider to further confirm that the Higgs boson behaves the way the Standard Model posits it will.

In addition to the satisfaction of verifying that a particle predicted by mathematical theorists actually does exist, Farrington said that another consequence of knowing about the Higgs boson is that it may shed light on dark matter and dark energy, which are not part of the Standard Model. Perhaps the Higgs boson gives mass to dark matter as well.

Physical Sciences & Engineering Panel Discussion

Victoria Gill started this session by asking the participants what they plan to do next. Farrington said that she would love to get more precise determinations on known processes, reducing the error bars upon them. And she will also embark on an open search for new long-lived particles—i.e. those that don’t decay rapidly—beyond the Standard Model.

Prodromakis wants to expand the possibilities of memristive devices, since they can be deployed anywhere and don’t need a lot of power. He envisions machine-machine interactions like those already in play in the Internet of Things as well as machine-human interactions. He knows he must grapple with the ethical implications of this new technology, and mentioned that it will also require a shift in how electricity, electronics, and computational fabrics are taught in schools.

Mishchenko is both seeking new properties in extant materials and making novel materials and seeing what they’ll do. He’s also searching for useful applications for all of his materials.

A member of the audience asked Farrington if, given all of the new research in quantum physics, we have new data to resolve the Schrӧedinger’s cat conundrum? But she said no, the puzzle still stands. That is the essence of quantum physics: there is uncertainty in the (quantum) world, and both states exist simultaneously.

Another wondered why she chose to look for the tau lepton as evidence of the Higgs boson’s degradation and not any other particles, and she noted that tau was the simplest to see over the background even though it does not make up the largest share of the breakdown products.

An online questioner asked Prodromakis if memristors could be used to make supercomputers since they allow greater computational capacity. He answered that they could, in principle, and could be linked to our brains to augment our capabilities.

Someone then asked Mishchenko if his technology could be applied into biological systems. He said that in biological systems current comes in the form of ions, whereas in electronic systems current comes in the form of electrons, so there would need to be an interface that could translate the current between the two systems. Some of his materials can do that by using electrochemical reactions that convert electrons into ions. But the materials must also be nontoxic in order to be incorporated into human tissues, so he thinks this innovation is thirty to forty years away.

The last query regarded whether the participants viewed themselves as scientists or engineers. Farrington said she is decidedly a physicist and not an engineer, though she collaborates with civil and electrical engineers and relies on them heavily to build and maintain the colliders and detectors she needs for her work.

Prodromakis was trained as an engineer, but now works at understanding the physics of devices so he can design them to reliably do what he wants them to do. And Mishchenko summarized the difference between them by saying the engineering problems are quite specific, while scientists mostly work in darkness. At this point, he considers himself an entrepreneur.

Innovating in Chemistry

Speakers

David P. Mills, PhD

The University of Manchester, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Chemistry Finalist

Matthew Powner, PhD

University College London, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Chemistry Finalist

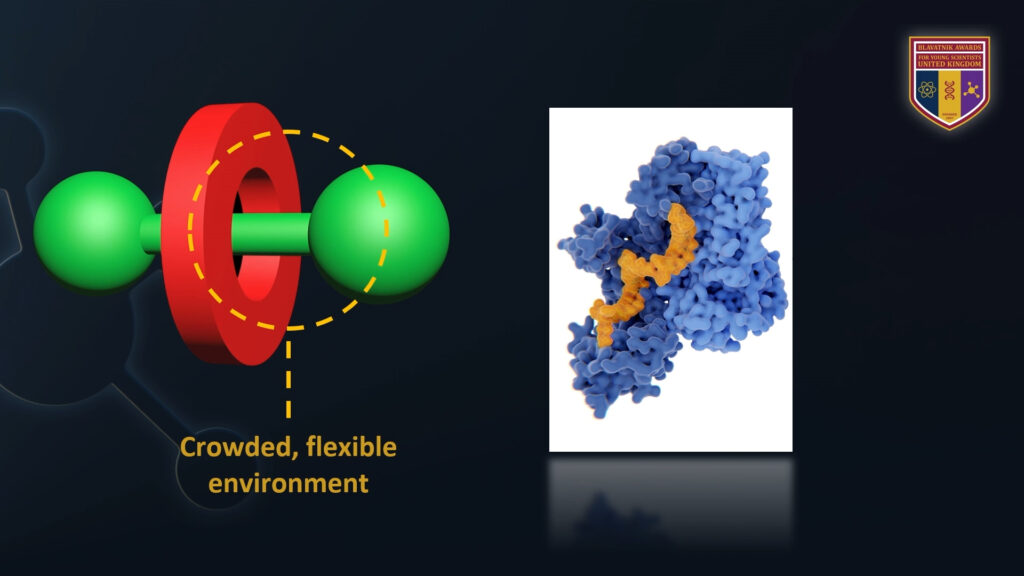

Building High Temperature Single-Molecule Magnets

David P. Mills, PhD The University of Manchester, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Chemistry Finalist

David Mills’ lab “makes molecules that have no right to exist.” He is specifically interested in the synthesis of small molecules with unusual shapes that contain metal ions, and using these as tiny molecular magnets to increase data storage capacity to support high-performance computing. Mills offers a bottom-up approach to this problem: he wants to make new molecules for high density data storage. This could ultimately make computers smaller and reduce the amount of energy they use.

Single-Molecule Magnets (SMMs) were discovered about thirty years ago. They differ from regular magnets, which derive their magnetic properties from interactions between atoms, but they still have two states: up and down. These can be used to store data in a manner similar to the bits of binary code that computers currently use. Initially, SMMs could only work at extremely cold temperatures, just above absolute zero. For many years, scientists were unable to create an SMM capable of operation above −259oC, only 10oC above the temperature of liquid helium, which makes them decidedly less than practical for everyday use.

Mills works with a class of elements called the lanthanides, sometimes known as the rare-earth metals, that are already used in smartphones and hybrid vehicles. One of his students utilized one such element, dysprosium, in the creation of an SMM that was dubbed, dysprosocenium. Dysprosocenium briefly held its magnetic properties even at a blistering −213oC, the warmest temperature at which any SMM had ever functioned. This temperature is starting to approach the temperature of liquid nitrogen, which has a boiling point of −195.8°C. If an SMM could function indefinitely at that temperature, it could potentially be used in real-world applications.

When developing dysprosocenium, the Mills group and their collaborators learned that controlling molecular vibrations is essential to allowing the single-molecule magnet to work at such high temperatures. So, his plan for the future is to learn how to control these vibrations and work toward depositing single-molecule magnets on surfaces.

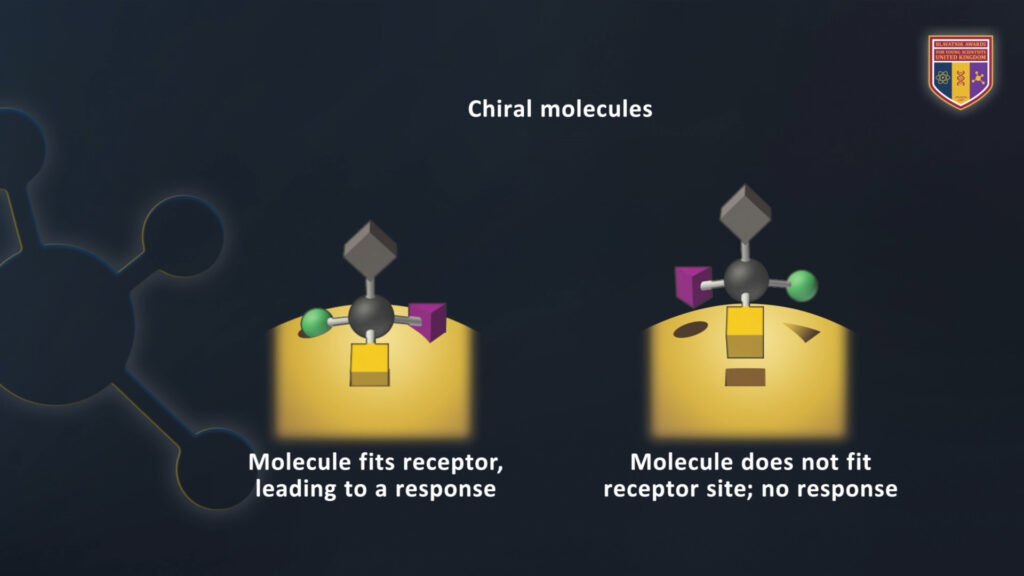

The Chemical Origins of Life

Matthew Powner, PhD University College London, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Chemistry Finalist

The emergence of life is the most profound transition in the history of Earth, and yet we don’t know how it came about. Earth formed four-and-a-half billion years ago, and it is believed that the earliest life-forms appeared almost a billion years later. However, we don’t know what happened in the interim.

Life’s Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) is believed to be much closer to modern life forms than to that primordial originator, so although we can learn about life’s common origins from LUCA, we can’t learn about the true Origin of Life. Where did life come from? How did the fundamental rules of chemistry give rise to life forms? Why did life organize itself the way that it did?

Matthew Powner thinks that to answer these vital existential questions, which lie at the nexus of chemistry and biology, we must simultaneously consider all of life’s components—nucleic acids, amino acids and peptides, metabolic reactions and pathways—and their interactions. We can’t just look at any one of them in isolation.

Since these events occurred in the distant past, we can’t discover it—we must reinvent it. To test how life came about, we must build it ourselves, from scratch, by generating and combining membranes, genomes, and catalysis, and eventually metabolism to generate energy.

In this presentation, Powner focused on his lab’s work with proteins. Our cells, which are highly organized and compartmentalized machines, use enzymes—proteins themselves—and other biological macromolecules to synthesize proteins. So how did the first proteins get made? Generally, the peptide bonds linking amino acids together to make proteins do not form at pH 7, the pH of water and therefore of most cells. But Powner’s lab showed that derivatives of amino acids could form peptide bonds at this pH in the presence of ultraviolet light from the sun, and sulfur and iron compounds, all of which were believed to have been present in the prebiotic Earth.

Chemistry Panel Discussion

Victoria Gill started this one off by asking the chemists how important it is to ask questions without a specific application in mind. Both agreed that curiosity defines and drives humanity, and that the most amazing discoveries arise just from trying to satisfy it. Powner says that science must fill all of the gaps in our understanding, and the new knowledge generated by this “blue sky research” (as Mills put it) will yield applications that will change the world but in unpredictable ways. Watson and Crick provide the perfect example; they didn’t set out to make PCR, but just to understand basic biological questions. Trying to drive technology forward may be essential, but it will never change the world the same way investigating fundamental phenomena for its own sake can.

One online viewer wanted to know if single-molecule magnets could be used to make levitating trains, but Mills said that they only work at the quantum scale; trains are much too big.

Other questions were about the origin of life. One wanted to know if life arose in hydrothermal vents, one was regarding the RNA hypothesis (which posits that RNA was the first biological molecule to arise since it can be both catalytic and self-replicating), and one wanted to know what Powner thought about synthetic biology. In terms of hydrothermal vents, Powner said that we know that metabolism is nothing if not adaptable—so it is difficult to put any constraints on the environment in which it arose.

He said that the RNA world is a useful framework in which to form research questions, but he no longer thinks it is a viable explanation for how life actually arose since any RNA reactions would need a membrane to contain them in order to be meaningful. And he said that synthetic biology—the venture of designing and generating cells from scratch, and even using non-canonical nucleic acids and amino acids beyond those typically used by life forms—is a complementary approach to the one his lab takes to investigate why biological systems are the way they are.

The Future of Research in the UK: How Will We Address the Biggest Challenges Facing Our Society?

Contributors

Stephen Brusatte, PhD

The University of Edinburgh, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Life Sciences Laureate

Sinead Farrington, PhD

The University of Edinburgh, 2021 Blavatnik Awards UK Physical Sciences & Engineering Laureate

Victoria Gill moderated this discussion with the Blavatnik laureates, Stephen Brusatte and Sinead Farrington. First, they discussed how COVID-19 affected their professional lives. Both of them spoke of how essential it was for them to support their students and postdocs throughout the pandemic. These people may live alone, or with multiple roommates, and they may be far from family and home, and both scientists said they spent a lot of time just talking to them and listening to them. This segued into a conversation about how the rampant misinformation on social media about COVID-19 highlighted the incredible need for science outreach, and how both laureates view it as a duty to communicate their work to the public by writing popular books and going into schools.

Next, they tackled the lack of diversity in STEM fields. Farrington said that she has quite a diverse research group—but that it took effort to achieve that. This led right back to public outreach and schooling. She said that one way to increase diversity would be to develop all children’s’ analytical thinking skills early on to yield “social leveling” and foment everyone’s interest in science. Brusatte agreed that increased outreach and engagement is an important way to reach larger audiences and counteract the deep-seated inequities in our society.

Lastly, they debated if science education in the UK is too specialized too early, and if it should be broader, given the interdisciplinary nature of so many breakthroughs today. Brusatte was educated under another system so didn’t really want to opine, but Farrington was loath to sacrifice depth for breadth. Deep expert knowledge is important.