“[C]onflict of interest is about more than money….it can come from political pressures and ideological pressures.”

Published February 18, 2021

By Melanie Brickman Borchard, PhD, MSc

Professor, NYU Grossman School of Medicine

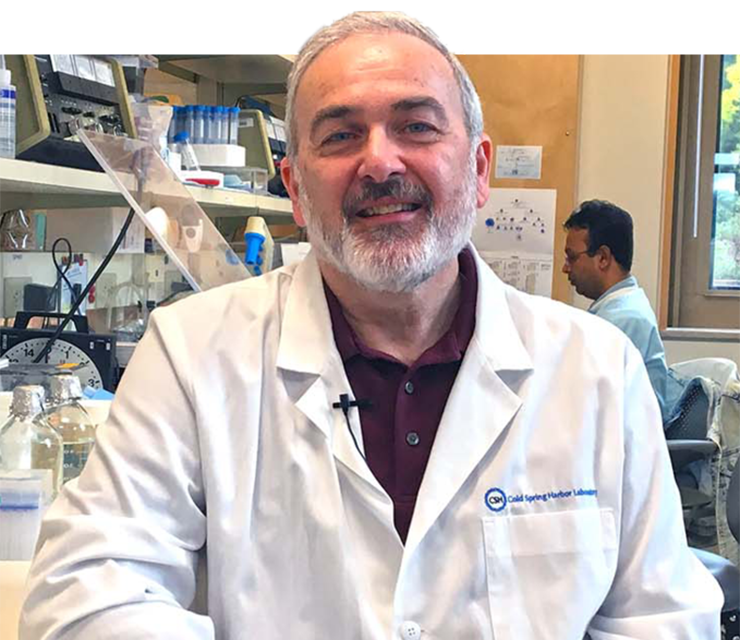

Arthur Caplan, PhD, says scientists, physicians, and their employers, must be on guard to ensure that quality research and good patient care remain front-and-center in a healthcare system rife with rewards for bias. Dr. Caplan is a professor of medical ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine. He advises presidents, government agencies, patient groups, and international organizations on bioethics.

He is a prolific researcher and author. We spoke with Dr. Caplan recently, and he shared five things doctors and medical researchers should keep in mind to help guard against bias in their work.

1) Demand transparency and be transparent.

As an employer or administrator, there are steps you can take to guard against bias in members of your staff. You can reward behavior that reduces opportunities for conflicts of interest.

There are a number of things we can do to manage conflict of interest. One is to demand transparency. Make sure that people tell us what their jobs are, what their responsibilities are, so you can assess whether they’re overworked or not doing enough of what they’re supposed to be doing. Many schools require those disclosures. Some prohibit taking a second job, some don’t let doctors moonlight, because they think it makes them too tired or it distracts them from their primary responsibilities.

In other situations, you can simply rule out certain relationships and say, ‘look, if you have a relationship with a company or a startup, and you think you’re making a useful medicine or vaccine, then you shouldn’t study whether it works or not. Farm that out to a third party.’ The process will be more independent and objective. If possible, you shouldn’t study what you own.

2) Recognize that transparency about ties to industry is important, now more than ever.

You can’t do anything with vaccines unless you’re talking to industry. They have the manufacturing capabilities. Plus, most of the basic science gets done in areas like vaccines with industry support, not through public or academic grants, or the work of academic institutions. So, in some sectors, there is no escaping the industry tie. You have to be transparent about that. You have to teach people how to manage that. You have to make sure that scientists and doctors understand they are going to be evaluated on the legitimacy of their work, not telling happy news to their funders. I think also we need more oversight. There should be more systematic review and challenging questioning by administrators, for more accountability. And you’ve got to beef up peer review. It is your best weapon against subtle, unconscious bias or deliberately fudging things to make them look good for increasing your salary or enhancing equity.

3) And speaking about peer review…. strengthening it must be a priority.

We need to bolster peer review. Peer review is getting weak. People don’t spend enough time teaching junior academics how to do it. The amount of resources and reward that come from doing peer review is somewhere between non-existent and nothing. But peer review is biomedicine and science’s best protection in looking at whether studies, evidence and information can be trusted. But if it’s just done pro forma, or people pass it off to ill prepared, overworked graduate students, or no one actually rewards you in terms of promotion for getting involved with it, then the best protection we have to verify evidence and verify that claims being made are true, is weakened significantly. And I do worry that the peer review system is not doing the job anymore to control for bias because it’s under-resourced.

4) Be cognizant of small favors, and factors other than money. As a doctor or scientist, don’t kid yourself about susceptibility to bias resulting from small incentives. And be aware that conflict is not always about money.

You have situations where doctors are prescribing medicine, and they say, ‘well, I prescribe the best medicine. I don’t believe that just because people take me to lunch, I’m going to start prescribing their medicine.’ But in fact, study after study shows that, subtly, small gifts, free lunches, free gas, and tickets to sporting or cultural events, have influence that really drive behavior. So, we may deny that small gifts can influence us, but time and again, psychology and behavioral science proves that they do.

Also, conflict of interest is about more than money. I know we ‘follow the money’ in thinking about conflict of interest and we tend to see people saying, ‘well, it’s money that generates conflict of interest problems.’ But I think it can come from other forces, too. I think it can come from political pressures and ideological pressures. I think we can see conflicts generated in the drive to succeed, the drive to be first, the drive for fame and honors. These things can create conflicts, too. So, in managing conflict of interest, it isn’t just figuring out where the money’s going, although that’s probably 85% of it. There are other forces we need to pay attention to as well.

5) Help the public understand how science works, with better science communication and with better teaching.

I think people will be more alert for conflicts of interest if they understand how science works. They won’t necessarily just say, ‘okay, I trust what you were telling me.’ They may want to get more than one opinion. They may want to go to more independent and trustworthy sources, and not just accept the views of somebody who’s trying to sell them a particular potion or nostrum.

There needs to be more effort made in the medical and scientific communities to train people to be communicators, and if you are good at it, you should be encouraged and make that part of your career. And we’ve got to get better science teaching into our schools. We need elementary and secondary school teachers who can communicate effectively about science. The public is not going to make good decisions about how to weigh opinion and evidence if we don’t have good communicators in the classroom.

Read more about Dr. Caplan’s work: The Need to Accelerate Therapeutic Development: Must Randomized Controlled Trials Give Way?