Overview

First identified nearly a century ago for its essential role in maintaining bone health, vitamin D has recently undergone a renaissance of interest due to the resurgence of vitamin D deficiency and the identification of vitamin D receptors in tissues and cells outside the skeletal system. Indeed, a growing body of evidence indicates that vitamin D has several extraskeletal functions and plays a key role in the immune, cardiovascular, and nervous systems. Furthermore, a growing body of research links vitamin D status to health and vitamin D deficiency to the risk of developing certain diseases, including cancers, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. On September 21, 2012, basic science and clinical researchers gathered to discuss non-classical effects at the Vitamin D: Beyond Bone conference presented by the Abbott Nutrition Health Institute and The New York Academy of Sciences.

Speakers

Daniel D. Bikle, MD, PhD

University of California, San Francisco and VA Medical Center

Ricardo Boland, PhD

Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina

Sylvia Christakos, PhD

UMDNJ–New Jersey Medical School

Luigi Ferrucci, MD, PhD

National Institute on Aging

David G. Gardner, MD

University of California, San Francisco

Martin Hewison, PhD

University of California, Los Angeles

Lily Li

Mount Sinai School of Medicine

Anastassios G. Pittas, MD

Tufts Medical Center

Erica Rutten, PhD

Ciro +, Centre of Expertise for Chronic Organ Failure

Igor N. Sergeev, PhD, DSc

South Dakota State University

Carol L. Wagner, MD

Medical University of South Carolina

Sponsors

This event was sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Nutrition Health Institute.

Introduction

Keynote Speaker

Daniel D. Bikle

University of California, San Francisco and VA Medical Center

Highlights

- Two major forms of vitamin D are important for human health: vitamin D3, which is synthesized in sun-exposed skin, and vitamin D2, which is synthesized in certain plants.

- Vitamin D is obtained through diet and sun exposure in the form of inactive precursors. The biologically active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, is produced via a two-step enzymatic process, predominantly in the liver and kidneys.

- The classical function of vitamin D is to maintain the integrity of the skeleton by modulating calcium homeostasis, but recent studies have uncovered several extraskeletal functions.

- The current recommended dietary reference values for vitamin D may be inadequate, especially for those at risk for vitamin D deficiency.

Synthesis and metabolism of vitamin D

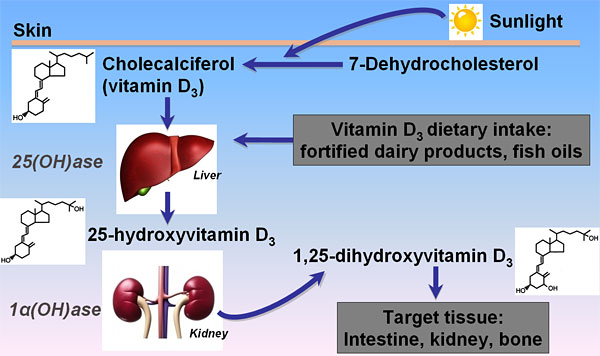

Vitamin D was first identified early in the 20th century as an essential nutrient. It is now recognized to comprise a group of fat-soluble prohormones, substances that are precursors to hormones but have minimal hormonal activity. Two major forms of vitamin D are important to human health—vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) and vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol)—which differ chemically only in the structures of their side chains. Vitamin D3 is produced in the skin through the action of sunlight (in particular, UVB radiation) on 7-dehydrocholesterol; analogously, vitamin D2 is synthesized in some plants and fungi via photoconversion of ergosterol.

Although sunlight exposure is our main source of vitamin D, it can also be obtained through diet or dietary supplements. Very few foods, however, naturally contain meaningful amounts of vitamin D. Good sources include cod liver oil, salmon, tuna, and other fatty fish, as well as fortified foods, such as milk, yogurt, and orange juice.

Vitamin D obtained through diet, supplements, or sun exposure is biologically inactive and must undergo metabolism to become active. Vitamin D2 and D3 are transported in the blood by vitamin D-binding protein to the liver and enzymatically hydroxylated at carbon 25 to form 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D). Although 25(OH)D is still biologically inert, it represents the major circulating form that is measured to assess vitamin D status. The active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D), is produced predominantly in the kidney but can also form in a variety of other tissues, including the skin and bone, and in immune cells. Compared with 25(OH)D, 1,25(OH)2D is generally not a reliable indicator of vitamin D status because it has a shorter half-life and its serum level changes in response to calcium, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone (PTH).

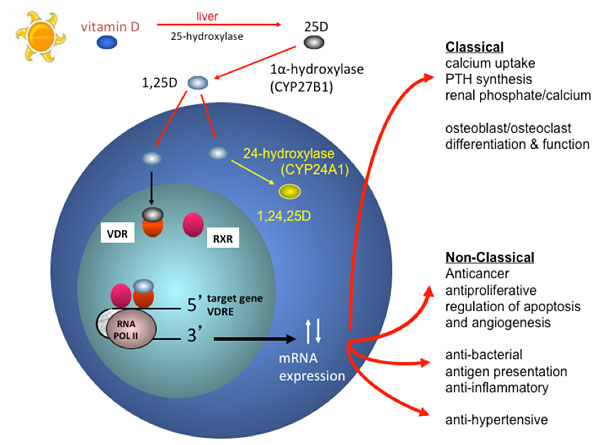

Vitamin D mechanism of action

The classical function of the active form of vitamin D is to maintain the integrity of the skeleton by regulating calcium and phosphorus homeostasis. In response to low blood calcium levels, the parathyroid gland secretes PTH, which induces expression of CYP27B1, the enzyme that catalyzes formation of 1,25(OH)2D. This active form binds to the vitamin D receptor (VDR)—which regulates gene expression by binding predominantly to vitamin D-responsive elements in the promoter regions of target genes—stimulating intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphate, the release of calcium from bone, and calcium re-absorption in the kidney.

Keynote address: Vitamin D dietary reference intakes

In 2010 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) evaluated health outcomes associated with vitamin D and calcium and proposed updated Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) values reflecting new data on optimal levels of these minerals. The IOM recommended a 25(OH)D serum level of at least 20 ng/mL (50 nM) but considered levels up to 50 ng/mL (125 nM) safe. A 600 IU daily intake of vitamin D is deemed adequate for most people but up to 4000 IU is considered safe. The IOM concluded that 97.5% of the U.S. population have 25(OH)D levels greater than 20 ng/mL and therefore do not need vitamin D supplementation.

Daniel Bikle from the University of California, San Francisco and VA Medical Center gave his perspective on these recommendations in his keynote address. He pointed out that the recommendations are for the general population, not patients, and are based only on studies of vitamin D’s classical effects on bone. Moreover, the IOM based its conclusion that nearly everyone in the U.S. population is vitamin D sufficient on data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), which were weighted toward healthy Caucasians and excluded the population living in the northern part of the country in the winter. Bikle surveyed additional studies that question the adequacy of the vitamin D status in many populations, concluding, “I question the IOM conclusion that 97.5% of the population in the U.S. maintain 25(OH)D levels above 20 ng/ml.”

Bikle also questioned whether the IOM recommendations meet the needs of the elderly, a population that is particularly vulnerable to vitamin D deficiency due to age-related decreases in cutaneous vitamin D production, dietary intake, intestinal absorption, 1,25(OH)2D production, and intestinal response to 1,25(OH)2D. He surveyed data on the relationship between vitamin D status and bone density, mobility, fall rates, and fracture risk and concluded that, “50 nM or 20 ng/ml [may not be optimal] for the elderly individual who’s at the greatest risk of vitamin D deficiency on the one hand and of fractures on the other.”

Bikle recommended that particular subsets of the population be tested for vitamin D deficiency, including women and men over age 65 and 70, respectively; those who are institutionalized; those with dark complexions living in temperate latitudes; those who avoid the sun or dairy products; those with osteoporotic fractures; those with malabsorption; those undergoing bariatric surgery; those with chronic kidney disease; and those taking certain drugs that alter metabolism.

In recent decades researchers have uncovered several non-classical extraskeletal functions of vitamin D. The Vitamin D: Beyond Bone conference explored these, presenting vitamin D’s multifunctional role in immunity, cardiovascular health, cancer, pregnancy, infection, diabetes, cognitive function, and muscle function; its molecular mechanisms of action; and recent changes to nutritional guidelines. The conference encouraged cross-disciplinary dialogue, identified research gaps, and helped to build communities, develop partnerships, and translate basic research findings and epidemiological data into strategies that may promote public health.

00:01 1. Introduction; The IOM recommendations

16:23 2. Vitamin D deficieny in the elderly

22:07 3. Recommendation adequacy

30:00 4. Who should be tested?

38:58 5. Therapeutic considerations

43:00 6. Summary and conclusions

Non-classical Roles of Vitamin D, Part 1

Speakers

Sylvia Christakos

University of Medicine and Dentistry New Jersey (UMDNJ)–New Jersey Medical School

Martin Hewison

University of California, Los Angeles

David G. Gardner

University of California, San Francisco

Carol L. Wagner

Medical University of South Carolina

Highlights

- Vitamin D inhibits the growth of breast cancer cells in vitro.

- Vitamin D reverses paralysis in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis.

- Vitamin D modulates, directly or indirectly, the function of several immune system cells.

- Vitamin D may exert a protective effect on the cardiovascular system.

- Supplementation with 4000 IU of vitamin D per day appears to be safe and effective for pregnant women.

Vitamin D’s impacts on cancer and multiple sclerosis

In addition to its principal role in the regulation of calcium homeostasis, recent in vitro and animal studies suggest that vitamin D inhibits the growth of breast, colon, and prostate cancer cells and may provide protection against certain immune-mediated disorders, such as type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis (MS). Sylvia Christakos from UMDNJ opened the meeting by discussing her research into the molecular mechanisms that underlie its impact on breast cancer and the immune system. Her studies have revealed that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits the growth of breast cancer cells in culture, in part by inducing the transcription factor and potential tumor suppressor protein C/EBPα (providing evidence that C/EBPα may be a candidate target for breast cancer treatment).

Christakos also described research demonstrating that vitamin D suppresses the development of experimental allergic encephalitis (EAE), the mouse model of MS. She investigated vitamin D’s effects on a class of helper T cells that produce the inflammatory cytokine IL-17, which has been reported to play a critical role in mediating inflammatory responses and autoimmune diseases, including MS. 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited the transcription of IL-17 in human CD4+ T cells in vitro and, in in vivo studies in EAE mice, down-regulated IL-17 levels in CD4+ T cells and reversed the onset of paralysis. These findings suggest that inhibition of IL-17 transcription may be one mechanism by which 1,25(OH)2D3 exerts its immunosuppressive effects. “Many of the same genes are present in humans and mice, and they act similarly, so minimally the findings … may suggest mechanisms involving similar pathways in humans that could lead to the identification of new therapies,” Christakos concluded.

00:01 1. Introduction and overview

04:12 2. Vitamin D’s impact beyond the skeletal system

11:24 3. Vitamin D and breast cancer

18:11 4. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis

25:32 5. Summary, acknowledgements, and conclusions

Vitamin D in immune function and disease prevention

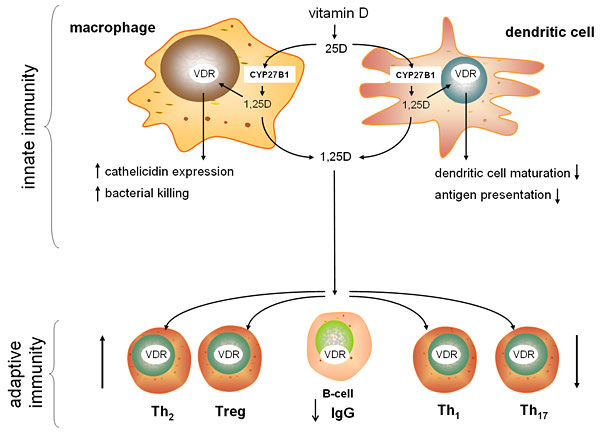

Martin Hewison from the University of California, Los Angeles expanded the discussion of vitamin D’s potent immunomodulatory effects, focusing on cellular machinery that mediates the activities of the adaptive and innate immune systems. Nearly all immune system cells express the vitamin D receptor (VDR); cells of the innate immune system, including macrophages and dendritic cells, also express the enzyme CYP27B1, and thus can activate 25(OH)D locally. Hewison’s research has shown that locally-activated vitamin D in macrophages can trigger the up-regulation of antibacterial proteins, such as LL37 (also known as cathelicidin), and can enhance the killing of bacterial pathogens. Ex vivo studies of human innate immune cells revealed that LL37 expression levels vary with vitamin D status, suggesting that vitamin D deficiency may potentially impair the LL37-mediated response to infection. Cytokines produced by other immune system cells enhance or suppress this vitamin D-mediated immune response by modulating vitamin D metabolism within innate immune cells.

Hewison’s group also discovered a similar intracrine vitamin D system in dendritic cells (DCs)—innate immune cells that primarily deliver bacterial antigen to cells of the adaptive immune system. In this case, locally-activated vitamin D inhibits DC maturation, thereby suppressing antigen presentation and indirectly modulating helper T-cell function. Hewison noted that the active vitamin D produced by DCs, as well as by macrophages, can also act in a paracrine fashion to directly regulate the function of all the various T-cell types by modulating the expression of key T-cell genes. Thus, vitamin D appears to promote immune tolerance and to suppress inflammation and autoimmunity.

Investigating the link between vitamin D status and autoimmune diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Hewison’s lab found that inducing short-term vitamin D-deficiency in mice increased the severity of experimentally-induced IBD. Vitamin D-deficient mice exhibited decreased expression of an antibacterial protein in the gastrointestinal tract and increased levels of bacteria in the colon, suggesting an additional antibacterial function for vitamin D and a potential interaction between IBD and the microbiota.

Hewison ended his talk with a look at vitamin D’s immunomodulatory function during pregnancy. Pregnant women tend to be vitamin D deficient. Hewison’s research has uncovered antibacterial and anti-inflammatory actions of vitamin D in placental trophoblast cells, suggesting that vitamin D deficiency may have implications for fetal development, preterm birth, fetal programming of adult disease, and maternal blood pressure. Hewison concluded by suggesting that vitamin D deficiency might impact a wide range of immune-related disorders.

00:01 1. Introduction

03:00 2. Vitamin D and bacterial killing; Tuberculosis and other disease studies

12:55 3. CYP27B1/VDR interactions; Inflammatory bowel disease and the microbiota

20:18 4. Vitamin D and pregnancy

26:12 5. Summary, acknowledgements, and conclusions

Vitamin D during pregnancy and lactation

Carol L. Wagner from the Medical University of South Carolina continued the theme of vitamin D action during pregnancy and lactation, focusing on the results of her recent vitamin D supplementation trials in pregnant women. Wagner and colleagues have found striking evidence of global vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy, particularly among darker pigmented individuals. Epidemiological studies have revealed that vitamin D deficiency is linked with a higher risk of maternal preeclampsia, an increased risk of gingivitis and periodontal disease in the mother, impaired fetal growth, impaired childhood dentition, and an increased risk of infection by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

To determine the most effective safe dose of vitamin D for pregnant women, Wagner and colleagues conducted studies with two different populations of pregnant women, each split into groups receiving 400IU, 2000IU, or 4000 IU of vitamin D3 per day until delivery. The studies found that 4000 IU/day is needed to achieve vitamin D sufficiency (the IOM currently recommends a daily dose of 600 IU/day for the general population). Perhaps more surprisingly, 25(OH)D levels had a direct and positive influence on 1,25(OH)2D levels throughout pregnancy, which has not been observed at any other time in life. No adverse events were attributed to supplementation; in fact, Wagner noted a trend towards lower rates of pregnancy complications in the 2000 IU and 4000 IU groups, compared with the 400 IU group, and towards lower rates of comorbidities during pregnancy with increasing 25(OH)D levels. She concluded that 4000 IU/day is safe and achieves vitamin D sufficiency in pregnant women.

Wagner is now investigating how vitamin D status affects immune function in the mother and her developing fetus and whether maternal D supplementation meets the requirements of both the mother and her nursing infant.

00:01 1. Introduction; Earlier studies

05:50 2. Epidemiological data; The NICHD supplementation study

11:23 3. The Thrasher Study; Combined study datasets

18:25 4. The Kellogg Project; Supplementation and mother’s milk

23:23 5. Summary and conclusions

Vitamin D and the cardiovascular system

Recent studies suggest that vitamin D may have a protective effect on the cardiovascular system: vitamin D deficiency is associated with high blood pressure and heart enlargement in rats; patients with congestive heart failure have reduced levels of circulating vitamin D; and vitamin D and VDR activation inhibits heart enlargement in rodents. David Gardner from the University of California, San Francisco investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying vitamin D’s cardiovascular effects using mouse models with VDR selectively deleted in either cardiac myocytes or endothelial cells.

Deletion of VDR in myocytes resulted in myocyte enlargement and in expression of genes involved in hypertrophy. Deletion of VDR in mice genetically engineered to accumulate excess fat in myocytes—a condition known as cardiac steatosis that is associated with obesity and diabetes in humans—amplified the pathological effects of cardiac steatosis, suggesting that VDR deletion, and possibly vitamin D deficiency, may sensitize the heart to pathological stimuli. VDR deletion in endothelial cells in vitro impaired the vasorelaxation that normally occurs in response to acetylcholine neurotransmitter. Furthermore, VDR deletion in endothelial cells in vivo resulted in a greater increase in blood pressure in response to the vasoconstricting hormone angiotensin. Taken together, Gardner’s findings suggest that vitamin D and vitamin D analogues may be useful in the management of heart disorders that involve cardiac hypertrophy.

00:01 1. Introduction

03:21 2. VDR activators and hypertrophy; Liganded VDR and the cardiac myocyte

12:25 3. VDR deficiency and cardiomyophathic stimuli

20:28 4. VDR deletion in murine endothelial cells

25:37 5. Summary, acknowledgements, and conclusions

Non-classical Roles of Vitamin D, Part 2

Speakers

Igor N. Sergeev, South Dakota State University

Erica Rutten, Ciro +, Centre of Expertise for Chronic Organ Failure

Lily Li, Mount Sinai School of Medicine

Highlights

- Vitamin D induces apoptosis in fat cells, suggesting that it may one day be useful in the treatment and prevention of obesity.

- Vitamin D may help to preserve lung function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder.

- Vitamin D reduces the erythropoietin requirements of hemodialysis patients with end-stage renal disease.

Vitamin D and apoptosis in obesity

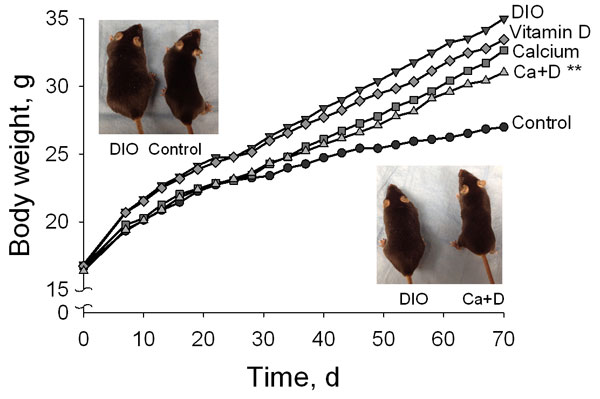

The discussion of the non-classical roles of vitamin D continued with a series of short talks by early career investigators. Epidemiological studies have associated low vitamin D status with an increased risk of obesity. Igor N. Sergeev from South Dakota State University has found that 1,25(OH)2D3 triggers programmed cell death in fat cells by inducing a sustained increase in calcium and by activating calcium-dependent proteases. He noted that inducing apoptosis in fat cells is emerging as a potential strategy for treating and preventing obesity. Using a mouse model of diet-induced obesity, Sergeev showed that supplementation with calcium and vitamin D reduced body fat and weight gain and improved biomarkers of adiposity. Sergeev suggested that vitamin D and calcium might prove useful in the treatment and prevention of obesity.

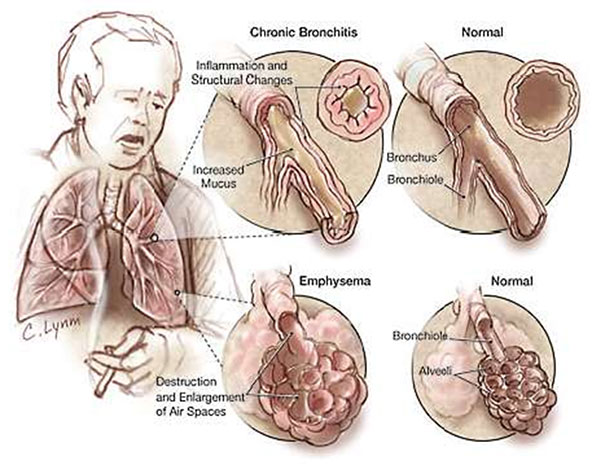

Vitamin D and lung function

Recent studies have found that vitamin D deficiency is prevalent among people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), an irreversible lung condition that includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema and is primarily caused by smoking. The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency increases with the severity of COPD. Erica Rutten from the Ciro +, Centre of Expertise for Chronic Organ Failure conducted a cross-sectional study of patients with moderate to very severe COPD: 58% were vitamin D deficient. She observed that lung function was positively associated with plasma vitamin D levels, even after correcting for age, gender, and body mass index, and concluded that vitamin D may play a role in lung pathology in patients with COPD.

Vitamin D and chronic kidney disease

Vitamin D deficiency is also common in hemodialysis patients with end-stage renal disease. Lily Li and colleagues from Mount Sinai School of Medicine are conducting an ongoing randomized controlled trial to determine whether correcting vitamin D deficiency decreases vitamin D-deficient hemodialysis patients’ requirements for erythropoietin, a hormone produced by the kidneys that is essential for red blood cell production. The group hypothesized that vitamin D deficiency causes dysregulation of innate immunity, leading to inflammation and altered iron metabolism and contributing to erythropoietin resistance. To date, vitamin D supplementation for 3 or 6 months has safely and effectively increased patients’ 25(OH)D levels and has reduced their requirements for erythropoietin. Ongoing studies aim to determine the immunologic effects of vitamin D repletion in these patients.

Policy and Clinical Applications

Speakers

Anastassios G. Pittas

Tufts Medical Center

Ricardo Boland

Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina

Luigi Ferrucci

National Institute on Aging

Highlights

- Low vitamin D status is associated with type 2 diabetes, but it remains unclear whether there is a causal relationship between vitamin D and diabetes.

- Vitamin D regulates skeletal muscle cell proliferation and function via classical and non-classical molecular mechanisms.

- Vitamin D status is associated with several aspects of physical and cognitive function in the elderly.

Vitamin D and type 2 diabetes

Vitamin D supplementation has emerged as a potential strategy for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. In his talk, Anastassios Pittas from Tufts Medical Center evaluated whether the available evidence supports a scientifically valid causal association between vitamin D and type 2 diabetes. Using observational data from the Nurses Health Study, Pittas has investigated the association between vitamin D and calcium intake and the development of type 2 diabetes. He found that women who reported the highest levels of calcium and vitamin D intake had a 33% lower risk of developing diabetes compared to those with the lowest intakes of both nutrients. He also observed an inverse relationship between plasma 25(OH)D concentration and risk of incident type 2 diabetes, such that women with higher levels of 25(OH)D had a lower risk of developing diabetes. Moreover, after repeatedly assessing vitamin D status over time in patients at risk for diabetes, he found that progression from pre-diabetes to diabetes declined with increasing concentrations of 25(OH)D.

These and other data suggest that vitamin D is associated with diabetes, but before accepting that a causal relationship exists, “we need to consider alternative explanations,” says Pittas. Because dietary intake of vitamin D and cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D are associated with healthy diets and behaviors, it is difficult to distinguish these potentially confounding factors from the effect of vitamin D itself, says Pittas. Furthermore, vitamin D status is associated with a variety of other factors, many of which are independently associated with diabetes, including physical inactivity, obesity, and dietary patterns. “So, is vitamin D simply a marker of increased risk for type 2 diabetes?” Pittas asked. “In other words, the strong association that we see with type 2 diabetes does not necessarily mean that supplementation would be beneficial.” Therefore, he says, randomized clinical trials are needed to test the hypothesis that vitamin D can modify diabetes risk.

Pittas’s randomized controlled trial—aimed to determine whether vitamin D supplementation would improve glucose homeostasis in patients at high risk for diabetes—showed that short-term vitamin D supplementation improved beta-cell function and attenuated the rise in glycated hemoglobin, a biomarker for diabetes. “In my mind, [vitamin D supplementation] for type 2 diabetes is a promising idea, but is yet unproven,” Pittas concluded.

00:01 1. Introduction

03:14 2. Biological plausibility; Specificity

05:58 3. Temporal relationship, association strength, dose response, and coherence

11:00 4. Experimental evidence and alternative explanations; Studies

19:40 5. Vitamin D, diabetes, and ethnicity

23:38 6. Summary and conclusions

Vitamin D and muscle function

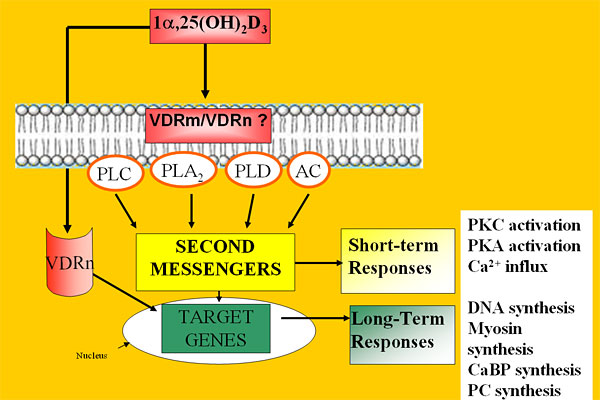

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that vitamin D plays a role in muscle function: muscle weakness and atrophy are common symptoms of vitamin D deficiency; 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulates muscle synthesis in vitamin D-deficient rats; and cellular studies have revealed the presence of the VDR in skeletal muscle. Ricardo Boland from Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina reviewed the molecular mechanisms by which 1,25(OH)2D3 regulates skeletal muscle cell proliferation and differentiation. In skeletal muscle cells, vitamin D can function via a classical genomic mechanism, triggering VDR-mediated changes in the expression of genes involved in muscle cell proliferation and differentiation.

Boland has discovered that vitamin D can also function in skeletal muscle cells via a non-classical mechanism involving the activation of transmembrane second messenger systems, calcium influx, and the growth-regulating signaling pathway known as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade. 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulates the translocation of VDR from the nucleus to the membrane, where it complexes with a calcium channel protein. At the cell membrane, VDR also forms a complex with the protein Src, which signals upstream of the MAPK cascade. These molecular mechanisms help to clarify how vitamin D regulates skeletal muscle cell growth and contractility and may aid the development of treatments for skeletal muscle disorders.

00:01 1. Introduction and background

05:45 2. Calcium influx; Capacitative calcium entry; SOC, TRP, and VDR

13:30 3. INAD-scaffold protein; Src tyrosine kinase; The ERK1/2 pathway

26:20 4. Akt activation; 1,25-dependent Src activation

33:12 5. Summary and conclusions

Vitamin D and Physical and Cognitive Function in Older Persons

Luigi Ferrucci from the National Institute on Aging reviewed the connections between vitamin D and aging. He and others have demonstrated that low 25(OH)D status is associated with mobility limitation and disability in older adults. He explored the basic pathways that may mediate these effects on physical and cognitive function in older persons, focusing on four major aging phenotypes that are related to the biological functions of vitamin D: changes in body composition, imbalances in energy production and utilization, homeostatic dysregulation, and neurodegeneration.

Ferrucci addressed changes in body composition first, showing that low serum levels of 25(OH)D are associated with a higher incidence of obesity and a higher probability of developing obesity, although the mechanisms remain unclear. In muscle tissue, expression of the VDR declines with age, and epidemiological studies have linked low vitamin D levels with loss of muscle strength and mass. These studies reveal some of the ways in which vitamin D may influence body composition.

Next, Ferrucci addressed energy homeostasis. High vitamin D levels are strongly correlated with higher levels of aerobic fitness and peak aerobic capacity, suggesting that low vitamin D levels may give rise to imbalances in energy production and utilization. Furthermore, VDR appears to localize in mitochondria in human blood cells, suggesting that vitamin D may influence energy homeostasis by regulating mitochondrial function.

In terms of homeostatic dysregulation, Ferrucci focused on vitamin D’s anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory actions. At the molecular level, 1,25(OH)2D3 may reduce inflammation by blocking the synthesis and action of prostaglandins and pro-inflammatory cytokines. A systematic review of 219 cross-sectional studies in the literature—designed to evaluate whether vitamin D levels are associated with the risk for autoimmune diseases and whether vitamin D supplementation can modify the course of the diseases—revealed that supplementation with vitamin D may reduce the risk of autoimmune disease. However, randomized controlled trials are needed to establish the clinical efficacy of vitamin D supplementation.

Finally, in terms of neurodegeneration, Ferrucci showed that low levels of vitamin D are associated with an accelerated decline in cognitive function, while higher levels of vitamin D intake are associated with a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Ferrucci has also identified an association between low serum levels of 25(OH)D and symptoms of depression in older men and women.

Ferrucci ended by calling for randomized, controlled intervention studies of vitamin D to determine whether it can slow the development of physical and cognitive disability.

00:01 1. Introduction

06:02 2. Pathways to cognitive and physical frailty; Changes in body composition

16:24 3. Energy imbalance; Homeostatic dysregulation

20:15 4. Neurodegeneration; Going forward; Conclusions

Panel Discussion

Moderator

Mandana Arabi

The Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science

00:01 1. Does one size fit all?

09:22 2. Sun avoidance; Categorization; Interpreting study data

21:24 3. Prescribing dosage; Fortified foods; Vitamin D2 vs. D3

35:30 4. Vitamin K2; Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin

Open Questions

- How do the extraskeletal biological responses observed in vitro and in animal models relate to human disease?

- Does the adjustment of vitamin D status correct vitamin D-mediated immune dysfunction?

- Does vitamin D status affect the composition of the gut microbiota?

- What are the circulating biomarkers of vitamin D-related immune function?

- What vitamin D supplementation level should be recommended for pregnant and lactating women?

- Is vitamin D supplementation beneficial to vitamin D-deficient patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

- Does vitamin D modify the risk of diabetes?

- Can vitamin D supplementation slow down the development of physical and cognitive disability in the elderly?

- When measuring vitamin D status, is it more meaningful to measure total 25(OH)D levels or only the fraction of 25(OH)D that is not bound to protein?

- Does vitamin D supplementation provide any clinical benefit other than its well-documented effects on bone?

Speakers

Organizers

Heike Bischoff-Ferrari, MD, MPH

University of Zurich, Switzerland

website | publications

Heike Bischoff-Ferrari is an MD and clinical researcher with specialty board certifications in general medicine, geriatrics, and physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. After her clinical training at the University of Basel, she was a fellow at the Department of Rheumatology, Immunology, and Allergy at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and was appointed to the faculty at Harvard Medical School. Bischoff-Ferrari holds an MPH from Harvard School of Public Health and a Doctor of Public Health from the Department of Nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health. Bischoff-Ferrari has an ongoing appointment as a visiting scientist at the Human Research Center on Nutrition and Aging at Tufts University. She holds a primary faculty appointment at the Department of Rheumatology at the University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland and received a Swiss National Foundations professorship in 2007. In 2008, she became the director of the Center on Aging and Mobility at the University of Zurich. Bischoff-Ferrari’s research focus is improving musculoskeletal health among the senior population with a focus on falls, fractures, and osteoarthritis. One particular interest is to define the role of vitamin D in the context of aging and musculoskeletal health.

Martin Hewison, PhD

University of California, Los Angeles

e-mail | website | publications

Martin Hewison is currently a professor in residence at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where his group has an established interest in the role of vitamin D in human physiology, and in particular the interaction between vitamin D and the immune system. Hewison gained his PhD in biochemistry from Guy’s Hospital Medical School, London and spent nine years at University College London. After moving to the University of Birmingham he established the UK’s major vitamin D research group, leading to an appointment as a professor in molecular endocrinology in 2004. In 2005 he joined Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles and moved to neighboring UCLA at the end of 2007. Hewison has published over 160 peer-reviewed manuscripts focused on various facets of steroid hormone endocrinology.

Nabeeha Mujeeb Kazi, MIA, MPH

Humanitas Global Development

e-mail | website

Nabeeha Mujeeb Kazi is managing director of Humanitas Global Development (HGD). She has directed high-profile global food-security initiatives and designed advocacy, public–private partnership, community mobilization, behavior change, and stakeholder engagement programs. Kazi’s team has collaborated with numerous high-profile international organizations including Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition, World Bank, World Health Organization, Save the Children, and UNICEF, among others. Kazi served as Senior Vice President and Partner at Fleishman-Hillard, a global communications firm, and has worked for the Clinton Foundation’s HIV/AIDS Initiative, focusing on Caribbean and African countries, and for the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in Mexico. Kazi serves on the boards of FINCA International and United Neighborhood Centers of America and has served on several taskforces and committees with partners like Scaling Up Nutrition, Millennium Villages, Feed the Future, and the New York Academy of Sciences. Kazi has dual Master’s degrees in public health and international affairs from Columbia University.

Hawley K. Linke, PhD

Abbott Nutrition

e-mail | website | publications

Hawley K. Linke is a senior scientist in the Global Discovery Group at Abbott Nutrition. Her early expertise arose from postdoctoral studies in mitochondrial gene identification at Stanford University Medical School and from her study of human viral gene expression for her PhD from UCLA’s Molecular Biology Institute. She joined Abbott Laboratories Diagnostics Division, Hepatitis-AIDS investigation group, before transferring to Abbott Nutrition. Her contributions to nutrition research include the development and exploitation of industrial-scale expression technologies producing genetically modified and unmodified human proteins for nutritional applications and clinical studies demonstrating therapeutic innovations in infant formula. As an expert in vitamin D, she advises the division on nutritional products to optimize its pleiotropic health benefits. She focuses on technologies for women’s health, neurogastroenterology, and manipulation of the microbiome.

Rosemary E. Riley, PhD, LD

Abbott Nutrition Health Institute

e-mail | website | publications

Rosemary E. Riley is senior manager for science programs at the Abbott Nutrition Health Institute, where she is responsible for developing and directing programs that educate health care professionals throughout the world on the importance of nutrition as therapy to improve patient outcomes. While at Abbott, Riley has worked on a variety of nutrition initiatives, including a comprehensive, multidisciplinary medically supervised weight management program, geriatric nutrition, sports nutrition, women’s health—with a focus on bone health—and diabetes. She also has experience in strategic discovery and evaluation of ingredients and technology to address these conditions.

Carol L. Wagner, MD

Medical University of South Carolina

e-mail | website | publications

As an academic neonatologist for more than 20 years, Carol L. Wagner has been involved in basic science, translational, and clinical studies. She holds an MD from Boston School of Medicine. She completed both her pediatric residency and neonatalñperinatal fellowship at the University of Rochester. She is a professor of pediatrics and the associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Center at the Medical University of South Carolina. Wagner’s current research interests are vitamin D requirements during pregnancy and lactation and human milk bioactivity and its effect on gut maturation.

Mandana Arabi, MD, PhD

The Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science

Brooke Grindlinger, PhD

The New York Academy of Sciences

Keynote Speaker

Daniel D. Bikle, MD, PhD

University of California, San Francisco and VA Medical Center

e-mail | website | publications

Daniel D. Bikle is a professor of medicine and dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco and co-director of the Special Diagnostic and Treatment Unit of the San Francisco VA Medical Center. He has a long history in the area of vitamin D, performing a number of the initial studies in its metabolism in the kidney and more recently its extrarenal metabolism in the skin. Much of Bikle’s recent research has focused on the molecular mechanisms by which 1,25(OH)2D and its receptor (VDR) regulate gene expression, in particular during normal epidermal differentiation, wound healing, and hair follicle cycling and on the pathologic changes underlying epidermal carcinogenesis. Bikle is also a practicing endocrinologist with particular interest in metabolic bone disease and has written extensively on the interface between the laboratory and clinic with respect to the implications of the recent research in vitamin D function and its impact on patient care.

Speakers

Ricardo Boland, PhD

Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina

e-mail | website | publications

Ricardo Boland is superior investigator of the National Research Council (CONICET) and director of the Biological Chemistry Laboratories at the Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina. Boland obtained his PhD in biochemistry at the University of Missouri–Columbia. He completed postdoctoral training at St. Louis University School of Medicine and the Max-Planck Institute for Medical Research. He served as president of the Argentinean Societies for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Bone and Mineral Research. Boland’s research career has been mainly focused on the actions of vitamin D3 on skeletal muscle functions. His major contributions are the identification of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in this tissue; the characterization of signal transduction pathways involved in the regulation of the Ca2+ messenger system and myogenesis by 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3; and the demonstration of a functional role of the VDR in these events.

Sylvia Christakos, PhD

UMDNJ–New Jersey Medical School

e-mail | website | publications

Sylvia Christakos is a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ)–New Jersey Medical School. Christakos received her PhD from the State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo School of Medicine. She completed her postdoctoral training at the Roswell Park Memorial Institute, SUNY Buffalo School of Medicine, Department of Biochemistry and at the University of California at Riverside, California, Department of Biochemistry. Christakos has received continuous funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF) for the past 30 years. Her laboratory combines studies related to the functional significance of vitamin D target proteins using animal models with studies related to the molecular mechanism of 1,25(OH)2D3 action.

Luigi Ferrucci, MD, PhD

National Institute on Aging

e-mail | website | publications

Luigi Ferrucci is a geriatrician and an epidemiologist who conducts research on the causal pathways leading to progressive physical and cognitive decline in older persons. Ferrucci has made major contributions in the design of many epidemiological studies conducted in the U.S. and in Europe, including the European Longitudinal Study on Aging, the “ICareDicomano Study,” the AKEA study of Centenarians in Sardinia, and the Women’s Health and Aging Study. He was also the principal investigator of the InCHIANTI study, a longitudinal study conducted in the Chianti geographical area (Tuscany, Italy), which looked at risk factors for mobility disability in older persons. Ferrucci has refined the design of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging to focus more on normal aging, age-associated frailty, and factors associated with exceptionally healthy aging and longevity.

David G. Gardner, MD

University of California, San Francisco

e-mail | website | publications

David G. Gardner received an MS in biochemistry and an MD from the University of Rochester. He completed his residency training in Internal Medicine at the Massachusetts General Hospital before moving to the NIH to complete his fellowship in the Combined Endocrinology Training Program. He is the Mount Zion Health Fund Distinguished Professor of Medicine and chief of the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism at the University of California, San Francisco. His research interests are concentrated in cardiovascular endocrinology, particularly on the regulation of cardiovascular and renal function by vitamin D.

Martin Hewison, PhD

University of California, Los Angeles

e-mail | website | publications

Lily Li

Mount Sinai School of Medicine

Lily Li is a third-year medical student at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University. Li completed a one-year post-baccalaureate Intramural Research Training Award Program in immunology at the National Institutes of Health. She is currently pursuing a one-year Doris Duke Clinical Research Fellowship at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Anastassios G. Pittas, MD

Tufts Medical Center

e-mail | website | publications

Anastassios G. Pittas is an associate professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine, an adjunct associate professor of nutrition and policy at Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition, Science, and Policy, and a center scientist at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University. He received his MD from Cornell University Medical College, completed his residency at the New York Presbyterian Hospital, and completed a fellowship in endocrinology at Tufts Medical Center before joining the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at Tufts Medical Center. Pittas is the co-director of the Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman New York Foundation for Medical Research Diabetes Self-education Program and the associate director of the Endocrinology Fellowship program. Pittas also holds an MS in clinical research from Sackler School of Biomedical Sciences at Tufts University.

Erica Rutten, PhD

Ciro +, Centre of Expertise for Chronic Organ Failure

e-mail | website | publications

Erica Rutten holds a PhD from Maastricht University in Maastricht, the Netherlands, where she studied amino acid metabolism in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). At the Center of Expertise for Chronic Organ Failure (CIRO+) in Horn, the Netherlands, she leads research on body composition, nutrition, and metabolism. Rutten received a research grant from the Dutch Asthma Foundation in 2008. Her interests include malnutrition in COPD, obesity, osteoporosis, vitamin D, and nutritional intake in patients with chronic disease.

Igor N. Sergeev, PhD, DSc

South Dakota State University

e-mail | website | publications

Igor N. Sergeev has over 25 years of experience in academic research in biochemistry and nutrition. Sergeev received his PhD from the Institute of Biomedical Problems and a DSc from the Institute of Nutrition, both in Moscow, Russia. As professor of nutritional sciences at South Dakota State University, he directs research program in nutritional biochemistry and molecular nutrition. Sergeev achieved international acclaim for his work on vitamin D metabolism, vitamin D receptors, and calcium signaling. In the last decade, he has been recognized for his research on the role of cellular calcium and vitamin D in the regulation of apoptosis.

Carol L. Wagner, MD

Medical University of South Carolina

e-mail | website | publications

Nicholette Zeliadt

Nicholette Zeliadt resides Washington, D.C., where she writes about science for scientists and non-scientists alike. She has a background in biochemistry and nutrition, and a PhD in environmental health sciences from the University of Minnesota. In pursuit of science, she has traveled by ship to the South Pacific Gyre, traversed the Willamette Valley by bike, and encountered 12 of the planet’s 13 climatic zones. She has written for Scientific American, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, BioTechniques, and About.com.

Resources

Sylvia Christakos

Raghuwanshi A, Soshi SS, Christakos S. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105(2):338-43.

Dhawan P, Wieder R, Christakos S. CCAAT enhancer-binding protein alpha is a molecular target of 1,25dihydroxyvitamin D3 in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(5):3086-95.

Christakos S, Ajibade DV, Dhawan P, et al. Vitamin D: metabolism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39(2):243-53.

Christakos S, DeLuca HF. Minireview: Vitamin D: is there a role in extraskeletal health? Endocrinology. 2011;152(8):2930-6.

Joshi S, Pantalena LC, Liu XK, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) ameliorates Th17 autoimmunity via transcriptional modulation of interleukin-17A. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(17):3653-69.

Martin Hewison

Hewison M, Freeman L, Hughes SV, et al. Differential regulation of vitamin D receptor and its ligand in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170(11):5382-90.

Liu NQ, Hewison M. Vitamin D, the placenta and pregnancy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523(1):37-47.

Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311(5768):1770-3.

Liu N, Nguyen L, Chun RF, et al. Altered endocrine and autocrine metabolism of vitamin D in a mouse model of gastrointestinal inflammation. Endocrinology. 2008;149(10):4799-808.

Fabri M, Stenger S, Shin DM, et al. Vitamin D is required for IFN-gamma-mediated antimicrobial activity of human macrophages. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(104):104ra102.

Hewison M. An update on vitamin D and human immunity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;76(3):315-25.

David G. Gardner

Chen S, Gardner, DG. Liganded vitamin D receptor displays anti-hypertrophic activity in the murine heart [published online ahead of print Sep 16 2012]. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012.

Chen S, Law CS, Grigsby CL, et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of the vitamin D receptor gene results in cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2011;124(17):1838-47.

Glenn DJ, Wang F, Nishimoto M, et al. A murine model of isolated cardiac steatosis leads to cardiomyopathy. Hypertension. 2011;57(2):216-22.

Chen S, Glenn DJ, Ni W, et al. Expression of the vitamin D receptor is increased in the hypertrophic heart. Hypertension. 2008;52(6):1106-12.

Carol L. Wagner

Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Vitamin D and pregnancy: skeletal effects, nonskeletal effects, and birth outcomes Study [published online ahead of print May 24 2012]. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012.

Wagner CL, Taylor SN, Dawodu A, et al. Vitamin D and its role during pregnancy in attaining optimal health of mother and fetus. Nutrients. 2012;4(3):208-30.

Hollis BW, Johnson D, Hulsey TC, et al. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: double-blind, randomized clinical trial of safety and effectiveness. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(10):2341-57.

Johnson DD, Wagner CL, Hulsey TC, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is common during pregnancy. Am J Perinatal. 2011;28(1):7-12.

Hamilton SA, McNeil R, Hollis BW, et al. Profound vitamin D deficiency in a diverse group of women during pregnancy living in a sun-rich environment at latitude 32°N. Int J Endocrinol. 2010;2010:917428.

Igor N. Sergeev

Song Q, Sergeev IN. Calcium and vitamin D in obesity. Nutr Res Rev. 2012;25(1):130-41.

Sergeev IN. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces Ca2+-mediated apoptosis in adipocytes via activation of calpain and caspase-12. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384(1):18-21.

Sergeev IN. Calcium as a mediator of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced apoptosis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89-90(1-5):419-25.

Erica Rutten

Romme EA, Rutten EP, Smeenk FW, et al. Vitamin D status is associated with bone mineral density and functional exercise capacity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [published online ahead of print Apr 2 2012]. Ann Med. 2012.

Persson LJP, Aanerud M, Hiemstra PS, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with low levels of vitamin D. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38934.

Janssens W, Mathieu C, Boonen S, Decramer M. Vitamin D deficiency and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a vicious circle. Vitam Horm. 2011;86:379-99.

Black PN, Scragg R. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and pulmonary function in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Chest. 2005;128(6):3792-8.

Lily Li

Kiss Z, Ambrus C, Almasi C, et al. Serum 25(OH)-cholecalciferol concentration is associated with hemoglobin level and erythropoietin resistance in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;117(4):c378-8.

Matias P, Jorge C, Ferreira C. Cholecalciferol supplementation in hemodialysis patients: effects on mineral metabolism, inflammation, and cardiac dimension parameters. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(5)905-11.

Anastassios G. Pittas

Pittas AG, Nelson J, Mitri J, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and progression to diabetes in patients at risk for diabetes: an ancillary analysis in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):565-73.

Mitri J, Dawson-Hughes B, Hu FB, Pittas AG. Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on pancreatic b cell function, insulin sensitivity, and glycemia in adults at high risk of diabetes: the calcium and vitamin D for diabetes mellitus (CaDDM) randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(2):486-94.

Osei K. 25-OH vitamin D: is it the universal panacea for metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4220-2.

Pittas AG, Sun Q, Manson JE, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(9):2021-3.

Pittas AG, Dawson-Hughes B, Li T, et al. Vitamin D and calcium intake in relation to type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):650-6.

Ricardo Boland

Boland RL. VDR activation of intracellular signaling pathways in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;347(1-2):11-6.

Buitrago C, Costabel M, Boland R. PKC and PTPα participate in Src activation by 1α,25OH2 vitamin D3 in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;339(1-2):81-9.

Buitrago C, Boland R. Calveolae and caveolin-1 are implicated in 1alpha,25(OH)2-vitamin D3-dependent modulation of Src, MAPK cascades and VDR localization in skeletal muscle cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121(1-2):169-75.

Luigi Ferrucci

Mai X-M, Chen Y, Camargo CA Jr, Langhammer A. Cross-sectional and prospective cohort study of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and obesity in adults: the HUNT study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(10):1029-36.

Shardell M, D’Adamo C, Alley DE, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, transitions between frailty states, and mortality in older adults: the Invecchiare in Chianti Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(2):256-64.

Semba RD Chang SS, Sun K, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and pulmonary function in older disabled community-dwelling women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(6):683-9.

Ferrucci L, Studenski S. Clinical Problems of Aging. In: Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Jameson J, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:570-588.

Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Langa KM, et al. Vitamin D and risk of cognitive decline in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13):1135-41.

Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P, et al. Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels as determinants of loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia): the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5766-72.

Daniel D. Bikle

Rosen CJ, Adams JS, Bikle DD, et al. The nonskeletal effects of vitamin D: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(3):456-92.

Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, eds., Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010.

Bikle D. Nonclassic actions of vitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(1):26-34.

Newhook LA, Sloka S, Grant M, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency common in newborns, children and pregnant women living in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;5(2):186-91.

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, et al. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures with oral vitamin D and dose dependency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(6):551-61.