Learn about the long history of knowing about our food, our bodies, and ourselves and how that applies to our contemporary diets and lifestyles.

Published March 14, 2011

By Stephanie B. H. Kelly

The authority to make claims about food and bodily knowledge was not always so squarely situated in the hands of professional physicians and nutrition experts. In fact, as Harvard historian of science Steven Shapin explained in his January 26, 2011 talk at The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy) titled You Are What You Eat: The Long History of Knowing about Our Food, Our Bodies, and Ourselves, Europeans from antiquity to the early modern period, while seeking advice from experts in many aspects of their daily lives, remained very much their own physicians.

These Europeans lived in the era of a branch of Western medicine known as dietetics. Unlike its sibling disciplines of diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutics, dietetics was “not just called into play when [one] was manifestly unwell.” Instead, this particular and, it should be noted, remarkably stable body of knowledge focused on maintaining as well as restoring health through balance and moderation of the elements at play. Intricately connected to daily routines, behaviors and practices, dietetics was associated with the concepts of “regimen” and “hygiene,” and it prescribed an ordered, balanced life for its adherents.

These values might resemble, for example, aspects of certain modern cultural or religious traditions, but they are a far cry from the realm of modern medicine and present-day nutritional science, according to Shapin. Whereas a modern nutrition expert might advise you to “reduce your fat intake,” and a modern physician might prescribe medications to help you reduce your cholesterol, a 17th century dietetics expert or a reader of dietetic texts (or “dietaries” as they were known) might suggest you eat foods that match your “temperament,” including high-fat foods as long as they taste good.

The History of Dietetics

Delving into the history of dietetics is a fascinating journey in its own right, but there are other motivations for studying a set of historical practices now so divorced from our own lives, as well. If the history of dietetics provides us no useful framework for considering our present reality, why study it at all? The answer is relatively simple, as Shapin made clear.

Understanding the history of dietetics tells us a great deal about how people have thought of themselves in relation to their food and their surroundings. Furthermore, because of its unique blending of ethical and instrumental authority, dietetics and the course of history from that body of knowledge to modern medicine can help us comprehend how European societies came to segregate knowledge into the prescriptive and the descriptive, separating “what ought to be” from “what is.”

As scientific concepts of nutrition took over in the early 19th century, substantial authority was invested in these new scientific disciplines to speak about aspects of daily life that were formerly the domain of dietetics. How and why this change occurred are fundamental questions to the study of our own contemporary relationship to our food, to our bodies, and to the experts who study them. And so, as it turns out, the premise of our earlier question is flawed: the history of dietetics has much to say about our current condition.

What is (or was) Dietetics?

During his talk, Steven Shapin had the unenviable task of rendering familiar the vocabulary and the culture of dietetics, which was so pervasive as to be a “coordinating mechanism [for many aspects of life] in the late Middle Ages, even for ‘non-experts,'” but which today is a worldview entirely foreign to our own. He accomplished this feat by relating for his audience the fundamental principles of dietetics and by explaining the intuitive and perceptual ways individuals could access dietetics knowledge.

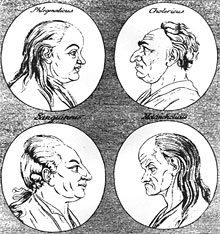

At its most basic, dietetics relied on the notion of four principal “elements” (air, water, earth, and fire) composing the physical world—everything from rocks to flies to humans to food. These four elements mapped onto four bodily “fluids,” or humors, respectively: the sanguine humor (blood), the phlegmatic (phlegm), the melancholic (black bile), and the choleric (yellow bile). To these fluids belonged certain qualities in different combinations.

For instance, yellow bile was believed to be both dry and hot, the qualities of the element fire. Inscribed in the combinations of four qualities, dry, hot, moist, and cold, one could find four personality types, one for each of the dominant humors. To this day, we can describe someone prone to anger as both “hot headed” and “choleric,” reflecting the cultural legacy of these concepts.

Adjusted for Each Person’s Specific Temperament

These qualities and personality types (also called “temperaments” or “complexions”) were maintained in health through balance and moderation. One should, according to dietetic advice, consume “hot” and “dry” foods to restore health when sick with “cold” and “moist” illnesses. To maintain health, one should match the food one consumes with one’s temperament. For instance, those of choleric tendencies should eat mostly foods with “hot” and “dry” qualities.

And because dietetics considered everything in terms of these same four qualities, it provided an integrative and coherent vocabulary that allowed for the description of relationships between diseases and their treatments, or people and their food, for example. This vocabulary and its corresponding culture of practice reached far into the fabric of everyday life; according to Shapin, “it belonged to you in ways that other science [does] not.” Dietetics advice could involve proscriptions against certain types of foods, but it could also venture into areas quite beyond the domain of modern nutritional science.

Shapin spelled out the areas on which a dietetics expert could advise, the realm of which included all the areas of someone’s life that could be altered in some way. These “six things non-natural” consisted of one’s airs (one’s surroundings), food and drink, motion and rest, sleep or waking, evacuations (including excretion, retention, and sexual release), and the passions of one’s soul (the emotions).

This list broadly encompassed many of the practices of everyday life and could include where someone should go on vacation or which direction his house should face, to name a few examples. Dietetic prescriptions were adjusted for each person’s specific temperament, so that a melancholic person (with a cold and dry temperament) was not constantly trying to counterbalance his or her temperament with sanguine treatments or vice versa.

The Good and the Good for You: The Instrumental and Ethical Authority of Dietetics

At this point it might seem that dietetics, insofar as it involved the treatment of disease through prescriptions for behavior changes, is not that different from aspects of modern primary care. However, dietetics can be distinguished on a number of fronts from the body of knowledge and the culture of practice belonging to modern medicine. Chief among these is “the way dietetics stood with respect to what was medical or scientific on the one hand and [to] what was moral on the other,” noted Shapin. For, as he explained, dietetics sat at the boundary of description and moral prescription.

Dietetics advice was therefore both instrumental and ethical in nature. The dietetic values of temperance and moderation, expressed in prescriptions such as “live to the golden mean” or “nothing too much” did not just resemble the four cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance, they affirmed them. Dietetics told people not just what was good for them (nutritionally, physically, mentally, etc.), but also what was good morally. Those who followed such direction would benefit materially, through the maintenance of their health, but also morally, through the affirmation of ethical truths.

“You are What You Eat”

“You are what you eat,” the phrase that began Shapin’s talk, takes on a level of meaning in this dietetics context beyond what is available in modern nutrition science’s vocabulary of “constituents.” People were characterized in the same way as their food, and just as knowing the correct description of someone’s qualities would lead you to the right description of their nature, knowing the right descriptors (hot, cold, moist, dry) for their food would tell you its nature as well. Knowing the nature of your food would allow you to predict how it would interact with your digestive system and whether it would make you sick, among other aspects of its behavior.

Furthermore, this analysis could be used to understand not simply the nature of people in the present, but also how they retained that temperament over time and what practices might drastically disrupt that nature in the future. In this way, custom was thought of as a second nature because people believed that a lifetime of custom, of eating behaviors and the like, could remake someone’s nature. In this framework, one had good reason to fear radical changes to lifestyle or drastic imbalance of the humors, and maintenance of that balance through dietetics knowledge became all the more important.

Dietetics and Expert Knowledge

Given the implications of a humoral imbalance, early modern Europeans clearly needed a reliable source of dietetic knowledge, but that source could be found surprisingly close to home. Although the “dietaries” written by dietetic experts were one avenue of access to dietetics knowledge, self-knowledge and experiential knowledge were both extremely important parts of the culture of dietetics.

In an era where independent testing of blood pressure, heart rate, or any of the metrics so fundamental to modern primary care was unheard of, even the most expert physicians were very much dependent on the patients’ accounts of their own behaviors and symptoms. Even the treatments for illness were largely in the patients’ hands, as medications took a back seat to lifestyle adjustments.

But early modern Europeans could get by without seeking advice from experts at all, explained Shapin. In most instances, non-experts could reliably deploy dietetic knowledge simply by engaging in what Shapin called “analogical forms of reasoning” to relate the superficial (or obvious) characteristics of food to the qualities of its nature and consequently, to the food’s fate as it was digested, to whether it would make a particular person unwell. Most of these superficial qualities could be reliably ascertained through intuitive descriptions of the food’s texture, general appearance, and so on. A cantaloupe, for example, would be considered “cold” and “moist,” and a chili “hot.”

Quod Sapit Nutrit

Of the ways to determine whether and how a particular food would match one’s own qualities, taste was crucial. The Latin saying “quod sapit nutrit,” meaning “if it tastes good, it’s good for you,” was not a playfully insincere justification for indulgence, as it might be today, but was instead a rule of thumb for assessing the goodness of food. In general an aliment agreed with someone—that is, made him well, not ill, if it sat well on the stomach—if its qualities matched his temperament, and the same principle applied in the mouth.

What tasted good on the tongue clearly matched the tongue’s, and therefore the person’s, nature. In this framework, because the perceived qualities of the food and the nature of that food were identical; the categories of being and of experience were one and the same. And more importantly, as Shapin put it, “the tongue [was] a reliable philosophical probe into the nature of things.” Not since has the role of the tongue been quite as authoritative as it was in dietetic culture.

The Rise of “Constituent” Descriptions

Smell, taste, and other everyday experiential ways of knowing have become “philosophically devalued” with the disappearance of dietetics from formal medical training in the 1810s and 1830s and eventually from lay consciousness, according to Shapin. Although they are the vehicles for the study of art and beauty through connoisseurship, these senses are no longer thought to be reliable probes into the nature of things. Dietetics and its ontology of “qualities” gave way to the beginnings of modern nutritional science and, with it, to a world of “constituents,” such as proteins, carbohydrates, and fats.

Such a drastic change first in the content of professional medical education and then in the public understanding of concepts as fundamental as which foods are beneficial did not happen over night. To begin to think of foods in terms of what they were made of instead of in terms of their qualities took a great deal of adjustment. Initially medical doctors, trained in the burgeoning discipline of chemistry, began to describe foods in terms of their sweetness, alkalinity, acidity, and so forth. These descriptions were constituent-based but were nonetheless available in some respects to the lay public through personal observations and sensory experience.

Fuel versus Non-fuel

William Prout in the 1810s and Justus von Liebig in the 1830s, both chemists by training, helped move the authority to make claims about foods’ components further out of the reach of the untrained public. Liebig in particular thought of the body as a kind of engine in which digestion was one mechanical process among many. And, like an engine, the body required materials to construct it and “fuel” to run it.

The distinguishing feature of “non-fuel” for him was the presence of nitrogen—an assessment that could clearly only be made by chemical examination. Of course, today this category of “nutrients” includes much more than nitrogen-containing substances, but it is no less in need of chemical interpretation than it was in Liebig’s era. Ideas of fuel have not left public discourse, though from that century to this, calories have come to mean “the power of food” rather than something contained within it.

Evidence for the present-day centrality of scientific interpretation can be found in what Shapin called “one of the great artifacts of the role of the state and the relationship of expertise—the Nutrition facts label.” This label, required on all processed, purchasable foods, indexes “the achievements of nutritional science,” and most of its details are only known to the consumer on the condition of expert knowledge.

Without the testing and re-testing of foods by scientific experts, we cannot know, for example, the iron content or carbohydrate content of the foods we consume. And this reliance on one set of experts cements our dependence on yet another set—we cannot be our own physicians in the same way as were early modern Europeans, so we must turn to nutrition experts and other medical professionals for advice.

The New Vernacular of Scientific Constituents Shows the Power of Modern Science

Despite our reliance on the authoritative accounts of modern medicine, we still use this scientific language, as in “I have to watch my cholesterol,” as though there were no expert intermediary to our knowledge of our foods and our bodies. In fact, as Shapin understands it, this scientific language is part of who we are and of how we understand ourselves, though that was not always the case. He explained that the rise of scientific expertise to dominance played a role in reconstituting ourselves. As he put it, “We are what scientists say. We didn’t used to be.” Without criticizing this reality, he went on to articulate that this new vernacular of scientific constituents shows the power of modern science.

He clarified, however, that there are actually two ways to think about this power. One way is to consider the rise of constituent descriptions as a reflection of the medicalization of modern life—our lives as we understand them are more medical than they once were. But, Shapin qualified, it is also possible to see this “power” as an indication that the “reach of modern science is actually less than it once was.”

Under dietetics food and drink composed just one of six aspects of daily life over which medical advice (expert or not) reigned. And, whereas modern medicine is adamantly instrumental, advancing physical but not moral well-being, dietetics advice had moral dimensions. Today, we might look to religion or philosophy to tell us what is morally right; dietetics shows how science (of a sort) once dominated these spheres, too.

Then and Now: What Has Changed?

Shapin concluded his talk by asking how we might begin to think about the big picture, the fate of dietetics and the rise of nutritional science to replace it. How, he asked, can we describe what has changed and where that leaves us in relation to our bodies, our food, and our physicians? Two historical trends can guide an answer to this question.

The first of these, the separation of expertise and lay knowledge, occurred concurrently with the increasing professionalization of medicine. Dietetics asked people to be their own physicians in many respects, requiring them to report on, to sense, and to manage daily routines through illness and health. This system, by contrast to modern medicine, elevated the level to which each person monitored his medical well-being on a daily basis.

Explored during Shapin’s talk as a key distinction between dietetics and nutritional science, the separation of ethical prescription from instrumental description was increasing in other areas of western culture at the same time. As he explained, under dietetics “instrumental advice occupied much the same cultural terrain as moral advice,” and medical and moral assessments used the same sort of vocabulary and reached much the same conclusions as one another.

The division of the ethical from the instrumental in medicine belongs to the same historical move as the emergence of “the naturalistic fallacy” in philosophy around the turn of the 20th century. This fallacy says that, logically, one can’t move from an “is” statement to an “ought” statement—just because something is or has been a certain way, one should not assume it should (morally) be that way.

Balance and Moderation

Whereas the principles of balance and moderation once offered the means to an end (health) and an end in and of themselves (moral health), modern science provides means, but not ends. For us, equaling our consumption of healthy foods with that of unhealthy ones just for the sake of upholding balance would be nonsensical, and we would not dream of prescribing cantaloupe to someone simply because he was sluggish. Today we would not find, nor presumably welcome, a conversation with our nutritionist in which the concepts of sin, gluttony, and excess were deployed as medical advice.

But balance and moderation have not disappeared completely from public discourse about food. In fact, in a humorous turn, Shapin revealed that “what was once traditional dietetic counsel has become the property of agents in society with the least credibility” when it comes to food: fast food companies.

These companies use the idea of balancing healthy foods “with a little fun” to advertise the very foods nutrition experts would warn us against. Shapin’s parting remarks left the audience considering the role of dietetics principles in a world so very different from the 17th century world of their prominence: “Prudence, now an aid to profit, once the most authoritative dietary advice, now a cynical attempt to link the bad and the bad for you with the good and the good for you.”

Also read: Challenges in Food and Nutrition Science