Major advances were made in the development of chemical weapons between World War I and the Cold War. This would present scientists with a moral dilemma.

Published August 1, 2004

By Mary Crowley

“Of arms I sing, and the man,” man,” began the Aeneid, Virgil’s epic poem on war and heroism, written in the first century BCE. Battle and humankind’s relationship to it is a timeless theme.

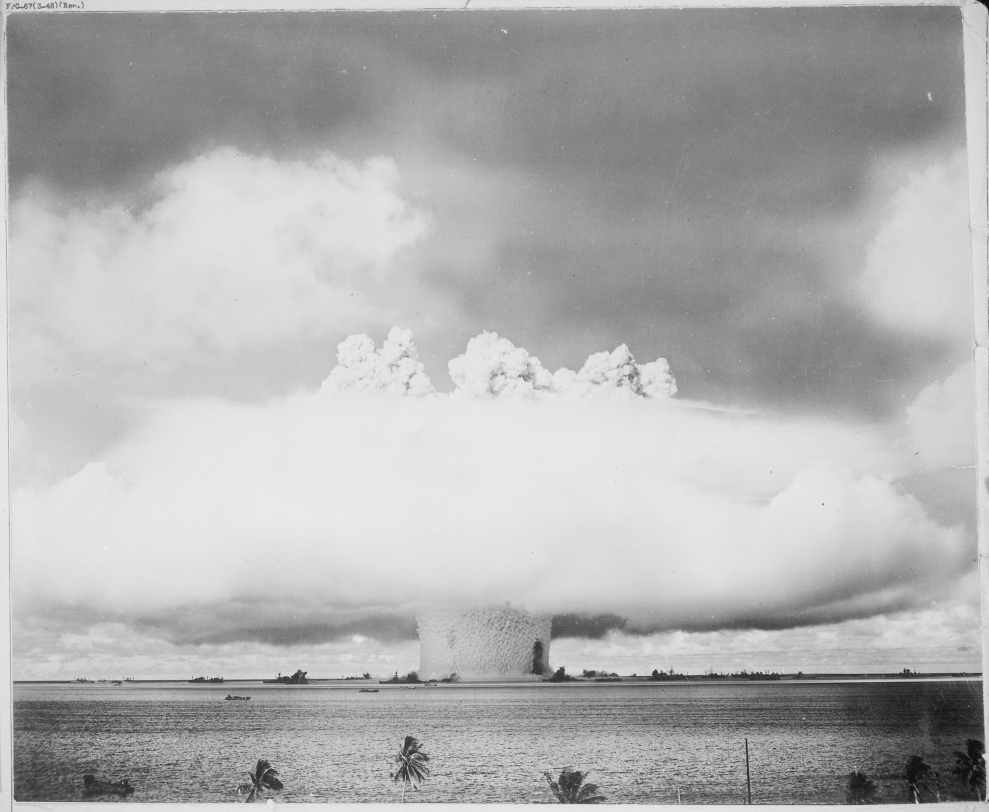

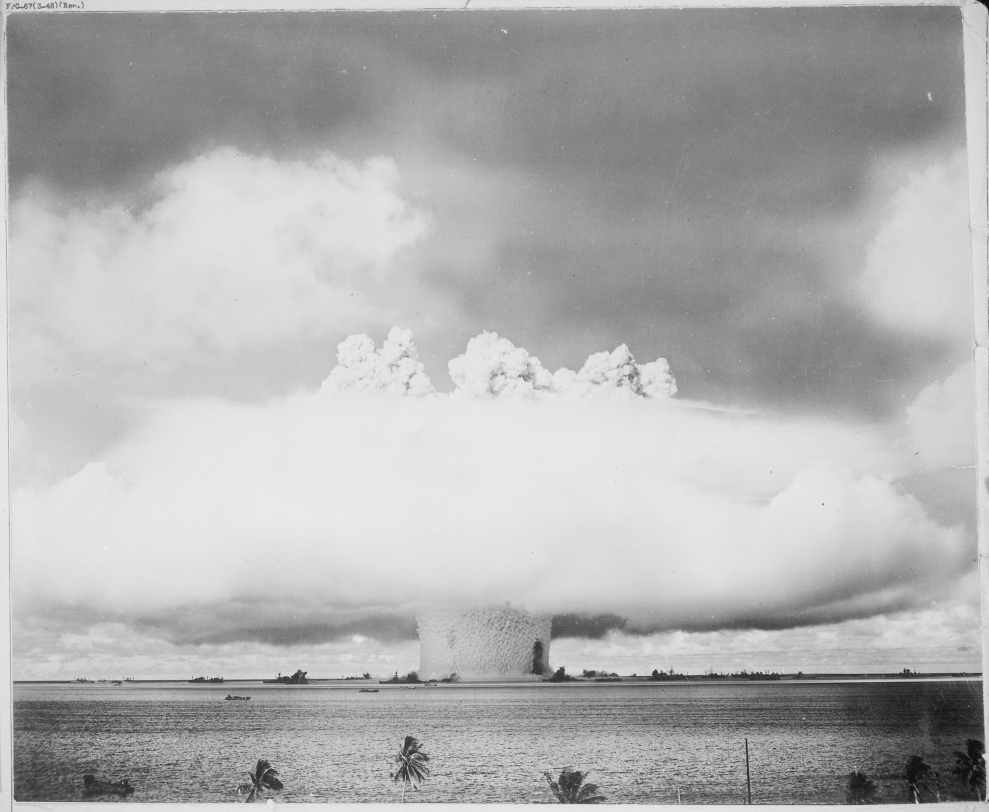

But war and weaponry took on new meaning in the 20th century, when nuclear arms created the potential to eliminate entire cities and even civilization. From the chemists who manufactured gas in World War I to the physicists who designed the atom bomb in World War II, scientists were at the fulcrum of a world literally in the balance.

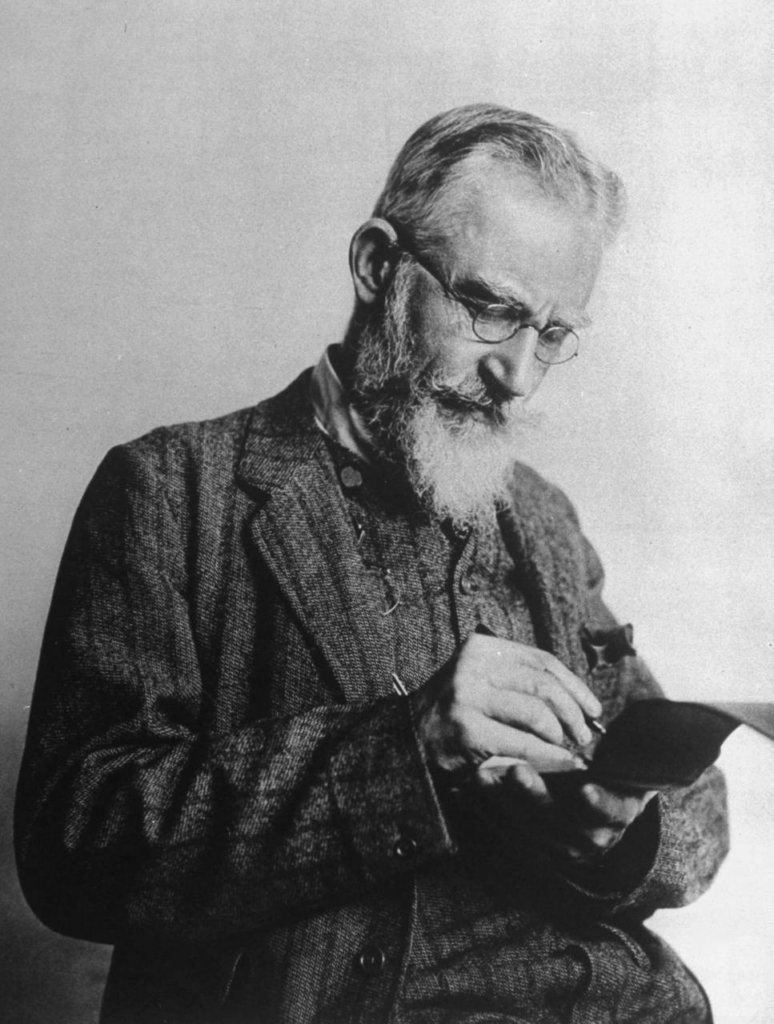

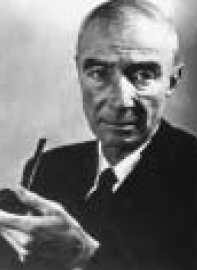

And they are still there now, in the post-9/11 era, this time with molecular biologists facing off against the shadowy enemy of bioterrorism. Hopefully, they have gleaned some insights from their forebears, particularly physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, who has come to represent the ethical dilemma that scientists face when called on to use their skills to defend their nation.

“The association of scientist, arms and the state is fraught with troublesome questions, many centering on whether the scientist’s obligation to the state requires deploying his or her expertise to hazardous, potentially destructive purposes and/or defending against them,” said Daniel J. Kevles, Ph.D., Stanley Woodward Professor of History at Yale University. Oppenheimer continues to fascinate us, prompting books, plays and even a coming opera because of the “vexing vitality of these issues,” he said at a recent meeting of The New York Academy of Sciences’ (the Academy’s) History and Philosophy of Science Section.

Chemists at War

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 condemned the development of chemical weapons (despite objections from the Americans and the British). The ban, instituted because of fears that chemical weapons like gas could be used against cities and civilians, demonstrated “the widely supported belief, even in military circles at the time, that at the opening of the 20th century civilian populations should not be fair game in warfare among the advanced civilized nations,” said Kevles.

But by the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, the Institute of Chemistry in Germany was trying to produce nitric acid for munitions. The Institute was headed by Fritz Haber, the “father of chemical warfare,” who with Carl Bosch won a Nobel Prize in 1918 for devising a method to fix nitrogen from the air. As Haber envisioned it, gas released from cylinders got around The Hague Convention’s prohibition against delivering it via projectiles. Indeed, Haber himself led the first gas attack at Ypres, in Belgium, in April 1915.

Public Opposition to Chemical Weapons

In response, the Allies quickly implemented their own programs. When the United States joined the battle in 1917, it established the Chemical Warfare Service, involving some 700 chemists and more than 20 academic institutions. Quite rapidly, the letter of The Hague Convention was ignored, as well as its spirit, as the French began using gas shells to better disperse the noxious agent. By war’s end, there were an estimated 560,000 gas casualties.

Artists and writers depicted the horrors of gas attacks. A poll of Americans showed such overwhelming opposition to chemical weapons that a government advisory committee noted, “The conscience of the American people has been profoundly shocked by the savage use of scientific discoveries for destruction rather than for construction.”

Nonetheless, as the Allies were poised for victory in 1918, “gas was hailed as a triumph of Allied industry,” said Kevles. Should the war have continued, the U.S. and Britain had plans to aerially assault cities with chemical bombs, despite vehement opposition from many military officers, including General John J. Pershing. Chemical weapons were seen as a necessary evil. At hearings on Capitol Hill, General Amos A. Fries argued that the more deadly the weapons, “the sooner…we will quit all fighting.”

In part through lobbying by the gas industry and in part through support of veterans who counted gas a “humane weapon” that ended the war sooner, the Chemical Weapons Service received generous research funding. And American gas chemists “displayed no moral anguish about their wartime role,” according to Kevles. They agreed with Haber, who said that gas was “a higher form of killing.”

Physicists at War

Physicists played the starring role in World War II science. Early on, it was clear that this war would be “an unprecedented technological conflict,” one that would require physicists to enjoin the battle for more powerful weaponry, explained Kevles.

They were eager to do so. The Blitzkrieg in 1940 and other early assaults “established a new imperative for the social responsibility of science: Do whatever possible to meet the technological threat from fascist aggressors by forging an all out technological response in the democracies,” said Kevles. With the memory of Germany’s World War I surprise gas attack still raw, the Allies had no plans to be caught unaware. “The willingness to develop an atomic bomb, a dramatically unconventional innovation that promised to wipe out entire cities, was to prevent being beaten to the punch by the Nazis,” according to Kevles.

But the bomb never went off against its preferred target. By the time Fat Man and Little Boy were completed, the Germans had surrendered. The bombs were used instead against civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, even as Japan was on the brink of surrender.

The Oppenheimer Paradox

By the time the atom bomb was dropped, “moral sensibilities about bombing civilians had been almost completely shattered, among scientists as well as policy and opinion makers,” said Kevles. J. Robert Oppenheimer’s experiences during World War II and the postwar years poignantly capture the inherent ethical dilemmas of scientists at war.

World War II transformed Oppenheimer from “an otherworldly theoretical physicist into the internationally renowned creator and sage of American nuclear strength,” who was then humiliated and destroyed by “the vicious and bare-knuckled politics of national security,” described Kevles.

Oppenheimer entered the war years eager to apply his physicist’s craft against the Nazis. He was the research head of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, New Mexico, feverishly working to develop an atom bomb before the Germans did. In 1945 he wrote, “We recognize our obligation to our nation to use the weapons to help save American lives [and] we can see no acceptable alternative to military use.”

That the bomb was used against Japanese civilians horrified Oppenheimer. He publicly stated in 1947, “Physicists felt a particularly intimate responsibility for suggesting, for supporting, and in the end, in large measure, for achieving the realization of atomic weapons. Nor can we forget that these weapons, as they were in fact used, dramatized so mercilessly the inhumanity and evil of modern war. In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

A Dutiful Soldier of Science

Despite these reservations, he remained a “dutiful soldier of science” during the early Cold War years, when intense investment into the machines of war was considered essential for national security. Oppenheimer signed on to the plan for creating an H-bomb, and served on various government advisory boards on national defense, until he lost his security clearance in 1953. Most significantly, he was chair of the General Advisory Committee of the just-formed Atomic Energy Commission, which he claimed was supposed to “provide atomic weapons and good atomic weapons and many atomic weapons.”

“Oppenheimer is something of a paradox, embodying at one and the same time a sense of sin associated with the forging of nuclear weapons and a commitment to improving and multiplying those weapons for the sake of national security, a task that could lead to further sin,” contended Kevles. “Yet the power of nuclear weapons, the reach of new delivery systems, the utter vulnerability of cities, and the potential combustibility of the Cold War forced Oppenheimer and his fellow scientists to embrace their paradox, to accept both the anguish of their sin and the continuing responsibilities of national security.”

Biologists at War

The science warriors of our era – the biologists who are at the forefront of research that can be turned to new types of weaponry – face a similar paradox. “The horrendous events of September 11, 2001 placed bioterrorism high on the national security agenda,” noted Kevles. Biomedical researchers are confronted with a new dilemma: Much of their research can serve both the beneficent needs of health and the nefarious needs of terrorism.

Due to the contemporary global nature of biology, with thousands of journals easily accessible, the information is highly transparent – and the key agents of bioterrorism require relatively small-scale investments. Meantime, the funding stream for biology is rich. The National Institutes of Health earmarked $1.7 billion for bioterrorism research in fiscal 2003.

How biologists contend with this challenge is history waiting to be written. “The challenge posed by bioterrorism is unprecedented in the history of science, arms and the state,” concluded Kevles. “To deal with it, one would like from the country’s biomedical leadership the kind of courage, tenacity and vision that Robert Oppenheimer provided – an engagement with the problems of arms and the state that offers, to paraphrase the majority report on the hydrogen bomb, some limitation upon the totality of war, some cap to fear, some reassurance for mankind.”