From jobs to goods, the region’s transportation infrastructure is critical to economic prosperity of not just the tri-state, but the entire country.

Published March 1, 2001

By Veronica Hendrickson, Allison L. C. de Cerreño, Ph.D., and Susan U. Raymond, Ph.D.

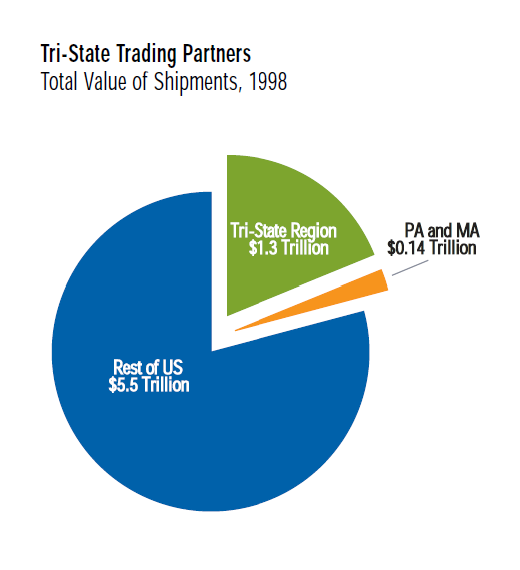

The Tri-State region represents 19% of the nation’s total value of product shipments annually, and 10% of the nation’s tonnage. But, New York and New Jersey are each their own most important trading partner. Roughly 49% of NY’s tonnage shipped remains in-state, for NJ that figure is 39%. Facilitating this intrastate and interstate regional trade are 115,000 miles of roads and 5,000 miles of rail lines, which knit the states together.

Annually, the three states originate and ship product worth more than $305 billion totally withinthe region. This represents nearly 25% of the value of all goods shipped domestically into and out of the region. That value also represents nearly half a billion tons of goods, or 38% of the tonnage shipped domestically into and out of the region.

Moreover, for both tonnage and value, beyond each other, the top trading-partners for all three states are two proximate states: Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. Maintaining the efficiency and effectiveness of the region’s transportation system is critical for the smooth and timely flow of goods and people, which in turn are needed for a strong regional economy.

How Many SUVs can You Fit in Your Garage?

New Jersey holds the dubious distinction of having the greatest number of drivers per square mile in the nation. But the big news on the road is not numbers; it is size. Truck motor vehicle registrations in all three states have increased between 37% and 43% since 1992. And the dominant force behind that growth has been the Sport Utility Vehicle. Between 1992 and 1997, SUV registrations grew by 133% in Connecticut, 138% in New York and 107% in New Jersey. In Connecticut, there is now one SUV for every 9 licensed drivers.

The Port Still Mater, but Region Faces Increased Competition

From the early 1700s through the mid twentieth century, the New York-New Jersey Port served as America’s trading center. By 1950, half of all the nation’s trade entered or left via its docks. Container shipping, born at Port Newark, promised to keep the Port in the forefront of trade. But the world changed. Ships became behemoths, with drafts approaching 45 feet, deeper than the Port’s channels at all but high tide.

Population and production shifted to the south and west of the nation. The Pacific Rim became an economic engine, overcoming Europe’s eastward pull. In turn, shipping shifted, south to Norfolk and Miami and West to Long Beach and Seattle. These ports invested in technology to manage trade growth efficiently. The NY-NJ port invested as well, in containerized cargo capacity and on- dock rail service. But the competition remained stiff.

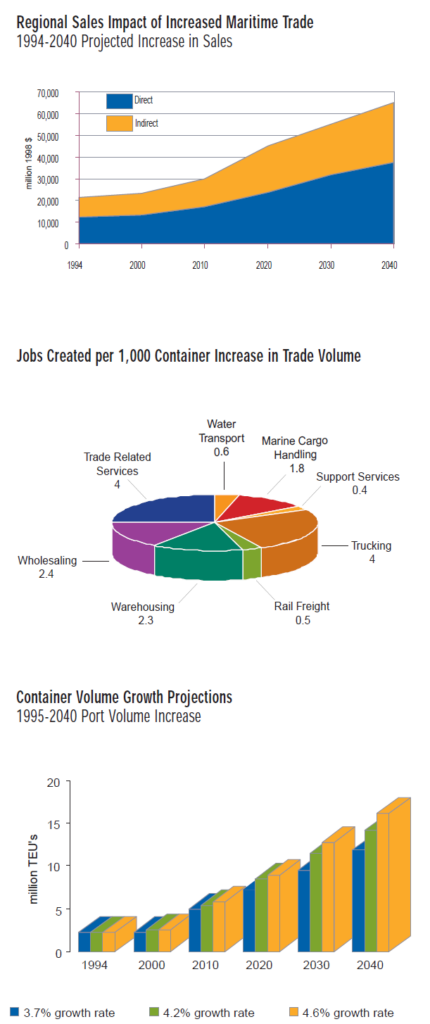

The price of not keeping pace with trade opportunity is high for the Tri-State region. The Port now accounts for 166,500 jobs in the 17-county metropolitan area. It generates $23 billion annually in economic activity, and saves the region’s citizens and businesses $750 million per year in transportation costs.

The Economic Impact of Globalization

And globalization is providing the opportunity to reassert the region’s shipping leadership, and to increase these economic benefits. Growth in maritime trade could generate an additional 238,000 jobs by 2040, nearly 3 times current levels. That level of growth would generate another 165,000 indirect jobs. Furthermore, Port job growth extends across skill levels, providing opportunity for management, but also for warehousing, transport, cargo handling and trucking personnel. Growth at the Port could be an anchor for job diversity.

But investment will be needed to cope with both growth and new transport technologies. For example, by 2020, 65% of all maritime trade will be carried on ships with drafts of more than 40 feet; 30% on ships with drafts exceeding 45 feet. Dredging the Port’s channels to accommodate such size is estimated to cost $3 billion.

Also read: Railroads and Transportation Infrastructure in the Tri-State

Sources

- United States Department of Transportation, 1998

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1997 Economic Census, “Vehicle Inventory and Use Survey,” December 1998.

- Port Authority of New York/New Jersey, Strategy Plan for Building and Expanding the Port of New York/New Jersey, “Building a 21st Century Port,” 2000.