Innovation challenges not only provide an interactive way for students and other innovators to embrace science, but they can also play a direct role in making the world a better place.

Published December 1, 2011

By Adrienne J. Burke

In a day and age when “thinking outside the box” is universally touted as the fastest path to scientific and technological innovation, incentive prize contests have come to be seen as one of the most creative ways to generate groundbreaking ideas. Here’s how it works: Broadcast a challenge with specific parameters and reward whoever solves it first. This simple but increasingly popular approach to tackling scientific problems goes so far outside the box, in fact, that winning solutions frequently come from completely unexpected or even unknown entities.

Consider the solvers in some recent contests: It was a concrete industry chemist in Illinois who figured out how to separate frozen oil from water in an Exxon Valdez oil spill cleanup challenge. A human resources professional posed a winning research question in a Harvard diabetes challenge. A Columbia University experimental astrophysicist won a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation challenge for suggesting a new approach to controlling malaria. And a team of West Philadelphia high-school kids built a super-efficient car that was a strong contender for an X Prize.

Even one of the most celebrated incentive contests in history is legendary for its surprising winner: a self-educated English watchmaker won Parliament’s £23,000 Longitude Prize for inventing the marine chronometer in the 18th century.

Ideas from Untapped Sources

Extracting ideas from untapped sources is largely the point of incentive contests. Proponents of the approach, which is sometimes called crowdsourcing or open innovation, frequently quote the wisdom of Sun Microsystems founder Bill Joy: “No matter who you are, most of the smartest people work for someone else.” When a problem has stumped your field’s experts, they say, casting the net to a broader, more diverse, and multidisciplinary population can yield amazing solutions. In fact, studies by Harvard Business School professor and innovation researcher Karim Lakhani have shown that winning solutions in challenge contests are most likely to come from solvers whose area of expertise is six disciplines removed from the problem.

At Scientists Without Borders, a program conceived by The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy) in conjunction with the United Nations’ Millennium Project, a web-enabled platform for seeking and suggesting solutions to science and technology challenges in the developing world is yielding input from a global and multidisciplinary set of innovators. The same is true at the Gates Foundation, where Program Officer Andrew Serazin says the five-year, $100 million Grand Challenges Explorations initiative to promote innovation in global health has successfully harvested ideas from a highly diverse set of people. “We’ve gotten some promising projects out of it, and we’ve gotten as much value out of reading applications,” he says.

Low Startup Costs

The startup costs for getting into the challenge-posing game can be surprisingly low. Platforms such as Scientists Without Borders and businesses like InnoCentive, IdeaConnection, NineSigma, and OmniCompete that facilitate contests for so-called “seekers,” make it easy for anyone to post a problem online and field solutions from around the world. You don’t need to offer a huge monetary reward to sponsor a successful incentive contest, either. Serazin contends that as little as a few thousand dollars can draw contestants, and plenty of seekers on Puri’s site get input without offering any reward at all.

Even if your organization isn’t ready to post its challenges to the outside world, simply employing the philosophies and practices of incentive contests can spur innovation within your own workplace. InnoCentive CEO Dwayne Spradlin notes, “The challenge-based approach is a fun way to get people inside an organization involved in solving a problem.”

Henry Chesbrough, the executive director of the Center for Open Innovation at University of California, Berkeley, Haas School of Business says, “Any organization has biases, myopia, previous experiences that advantage certain approaches and discourage or discount others. A contest can transcend these cognitive barriers.”

Contest Limits and Benefits

While useful, contests also have their limits. And not every scientific puzzle lends itself to the challenge format. Experts agree that, to be suitable, a problem must be able to be very well defined, and the parameters for winning very clear.

“An explicitly identified goal is essential to focusing the world’s attention on a challenge,” Serazin says, “and the achievement of the goal must be measurable.” He points to contests such as the Ansari X Prize, which promised $10 million to the team that could build and launch a spacecraft capable of carrying three people to 100 kilometers above the earth’s surface twice within two weeks. Contestants’ performance could be measured so that it would be clear who the winner was. “In health and biomedicine, getting that kind of specificity is not easy,” he warns.

Nor should incentive contests be seen as a cheap way to outsource R&D. Forming and managing a challenge requires substantial internal knowledge and resources. The genome researcher Craig Venter hosted a DNA sequencing challenge for several years before turning it over to the X Prize Foundation to administer. With the level of expertise and management the contest demands, he says, “it costs several million dollars to run a contest to give away $10 million.”

As Chesbrough notes, prize competitions aren’t going to render the internal R&D department obsolete, but they can complement, extend, and inform it. A small but growing segment of the business world agrees with him. According to a widely cited study by the consulting firm McKinsey, almost $250 million was awarded to prize-winning problem solvers between 2000 and 2007.

Meeting the Challenge

Large corporations, small businesses, philanthropies, universities, government agencies, and nonprofits—from GE to the Gates Foundation, from NASA to Scientists Without Borders—are among the organizations now offering cash to outsiders who can meet their challenges. InnoCentive, one of the best known companies serving the incentive contest market, has hosted more than 1,000 challenges since 2001 and boasts a solver community of more than 200,000 individuals in 200 countries. Robynn Sturm, advisor for open innovation at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, says challenges should be a part of any innovation portfolio. Today, analysts estimate the incentive-based prize market at $2 billion and growing.

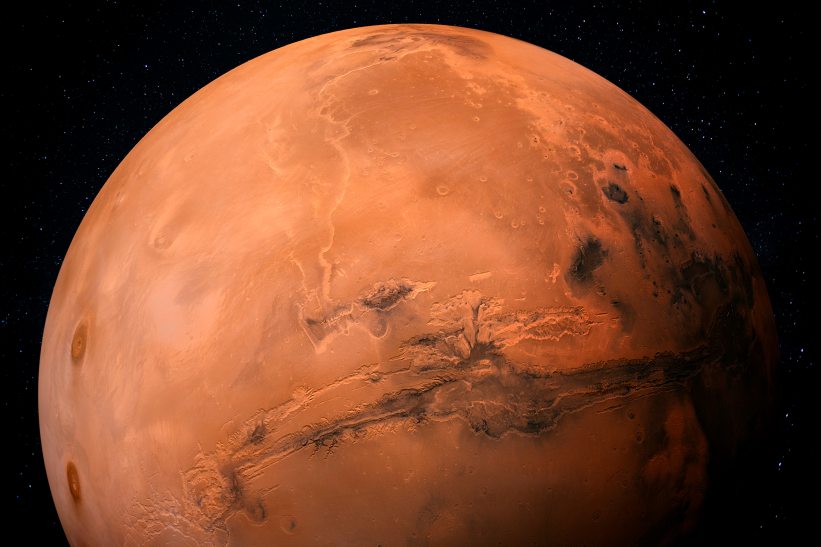

President Obama is accountable for some of that projected growth. He recently called on federal agencies to increase their use of prizes and challenges to spur innovation. “Prizes and challenges are not the right tool for every problem, but right now they’re being so underutilized that it’s safe for us to call on all agencies to increase their use,” says Sturm. Already, the White House-sponsored Challenge.gov website features nearly 60 government challenges, and a banner there encourages government agency leaders to “challenge the world.” Government-sponsored contests are inspiring citizens of all stripes to offer up novel solutions to national problems such as childhood obesity, energy storage, and keeping astronauts’ food fresh in outer space.

OSTP Deputy Director for Policy, Tom Kalil, says that, in addition to increasing the number and diversity of minds tackling a problem, contests offer several advantages over traditional grantmaking, including freeing the government to pay only for results, not for unfruitful research. The approach, he says, also “allows us to establish a bold and important goal without having to choose the path or the team that is most likely to succeed.”

Different Approaches

Adds Sturm, “Prizes and challenges allow you to see a number of different approaches all at once. With a grant or contract, you have to pick your course and cross your fingers. With a prize, you can say, ‘This is our goal, and we’re happy to pay anyone who hits it, however they do it.’”

Scientists Without Borders uses challenges as one part of an open innovation platform designed specifically to generate scientific and technological breakthroughs in global development. It enables members of the community to work together and combine their resources and expertise to take action and accelerate progress. Organizers believe the challenge approach will move the needle by generating, refining, or unearthing effective solutions and then getting them deployed as widely as possible.

Craig Venter notes one more benefit of incentive contests: they can serve as truth serum against exaggerated claims and marketing spiel. When Venter joined forces with the X Prize Foundation to establish the $10 million Archon Genomics X Prize the idea was to incite progress in genomic sequencing technologies and to get beyond what he considers to be industry spin about the state of the art.

The winner will be, specifically, the first team to build a device and use it to sequence 100 human genomes within 10 days or less, with an accuracy of no more than one error in every 100,000 bases sequenced, with sequences accurately covering at least 98 percent of the genome, and at a recurring cost of no more than $10,000 per genome. “You can’t fake it,” Venter says. “There will be clear winners for a set of standards.” If prizes and contests can incentivize people and provide a reality check of all the claims that are out there, he says, “then they can really help science move ahead.”

Incentivized in Academia

What does a scientist, lab head, or manager need to know to enter the challenge arena? Tom Kalil points to the Harvard Catalyst/InnoCentive Type 1 Diabetes Ideation Challenge as an example of how the scientific community can use challenges— both within an organization and more broadly—to generate not just technological solutions, but new research ideas.

With funding from the National Center for Research Resources, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center offered a cash reward for winning answers to the question, “What do we not know to cure type 1 diabetes?” Contestants were asked to formulate well-defined problems aimed at advancing knowledge about, and ultimately eradicating, the disease.

The challenge was open to the entire Harvard community as well as InnoCentive’s 200,000 solvers. Ultimately, nearly 800 respondents expressed interest in the contest, 150 submissions were evaluated, and 12 winners were each awarded a $2,500 prize. The winners included a patient, an undergraduate student, an MD/PhD student, a human resources representative, and researchers from unrelated scientific fields.

Promoting Collaboration

Eva Guinan, director of the Harvard Catalyst Linkages program and associate director of Clinical/Translational Research at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, says the contest itself was an experiment to see how the model could work in an academic biomedical environment, given that researchers are traditionally disincentivized from collaborating. She says top-down management support was one key to securing widespread participation. In an email to the tens of thousands members of the Harvard community, from deans to janitors, President Drew Faust endorsed every employee’s participation in the challenge, suggesting that it would “help stimulate innovative thinking and potential new understandings and therapies.”

“Companies need to open up and break down boundaries between departments,” Spradlin says. He points to a recent InnoCentive client—a large engineering organization that hosted an incentive contest internally, but opened the competition only to staffers with information technology backgrounds. “We told them to run the contest all over the company. The solution came from someone in the finance department.”

Be a Seeker and a Solver

Harvard’s Karim Lakhani suggests scientists can spur innovation in their own labs just by participating in contests, either as solvers or seekers. “Often scientists and PIs get narrowly focused in one area, but we know that being exposed to new questions and expanding your horizons can yield creativity,” he says. “There might be a very interesting problem out there that lets you directly export and apply knowledge from your field to a different field. That creative expression is worthwhile in itself, and working on another problem may unlock a problem in your field.”

For would-be seekers, he suggests a strategic approach: There might be problems you are stuck on, or a set of problems that aren’t high priority for your lab but need to be knocked off your list, he says. Those would be worth broadcasting to see if outsiders come up with interesting solutions. “Take a portfolio approach to your lab,” he says. “Decompose your problems and express them in modules. Then be strategic about them and say, ‘I think we’d benefit from outside perspectives here.’ It’s a very different way to do science.”

Not Just Motivated by Money

Edward Jung, founder and CTO of Intellectual Ventures in Seattle, says that crucial to results is the problem statement. “If you’re trying to invent the Boeing 787, you don’t put out a request to invent an airplane,” he says. “You divide it up into smaller, tractable pieces such as, ‘design a more efficient way of modulating turbine blades.’”

And Harvard’s Eva Guinan adds a word of caution: Before launching a challenge, “you really have to be convinced that it’s what your organization wants to do. There are a lot of people who aren’t believers.” With internal challenges, beware of managers who don’t buy in. “There can be complaints such as, ‘This person is working for me, and I don’t appreciate that they’re sitting on their computer working for someone else,’” Guinan says.

Others can be so hung up on the belief that the PhD is the smartest person in the room, that they’re not willing to consider input from anyone without an academic pedigree. “You have to be willing to push this as an issue of social and cultural change,” Guinan says. Karim Lakhani points to one more secret of incentive contests: Participants often aren’t motivated by the money. “Most people know they’re going to lose, but they participate anyway,” he says.

Instead, participants are drawn by the opportunities to be part of a group effort, work on an interesting problem, learn something new, achieve a clear goal, and get feedback on their work. “This is at the heart of why people do science,” he says.

What’s Next in Incentivizing Science?

At the forefront of new models for hosting challenges is the grassroots, collaborative approach to problem solving that Scientists Without Borders enables. While the platform is also host to competitive incentive-prize contests, such as a current PepsiCo-sponsored challenge that seeks ideas for curbing folic acid deficiency, it also enables users to seek input from the broad and global Scientists Without Borders community—engendering a teamwork approach to solving the challenges of the developing world. Organizers don’t just want people to find each other—they want them to work together and combine their resources and expertise to take action and accelerate progress.

Unique among organizations that facilitate challenges, Scientists Without Borders provides user-friendly online modules that allow anyone to frame and post a challenge, offers an expert advisory panel for guidance, and enables users to help each other solve problems regardless of where the challenges exist or users reside. Organizers call it a bottom-up, user-generated challenge model that will surface barriers on the ground, in the field, or at the bench that might otherwise be overlooked.

Whether in the global development niche that Scientists Without Borders fills or in a scientific laboratory looking to ignite its members’ creativity, open innovation tools like incentive contests and challenges can be powerful and inspiring ways to tap human ingenuity.

Learn more about the Academy’s Innovation Challenges.