While the nineteenth century’s greatest scientific debate was that over Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, the century’s other great scientific debate, almost forgotten now, posed problems even more vexing than the species question did.

Published November 11, 2005

By David Dobbs

The Other Debate of Darwin’s day

Asked to name the 19th century’s major scientific squabble, most people will correctly name the row over Darwinism. Few recall the era’s other great debate—regarding the coral reef problem—even though it was nearly as fierce as that over the species problem. The reef debate saw many of the same philosophical issues contested by many of the same players. These included Charles Darwin, the naturalist Louis Agassiz, and Alexander Agassiz, an admirer of the former and the son of the latter. Their tangled struggle is one of the strangest tales in science.

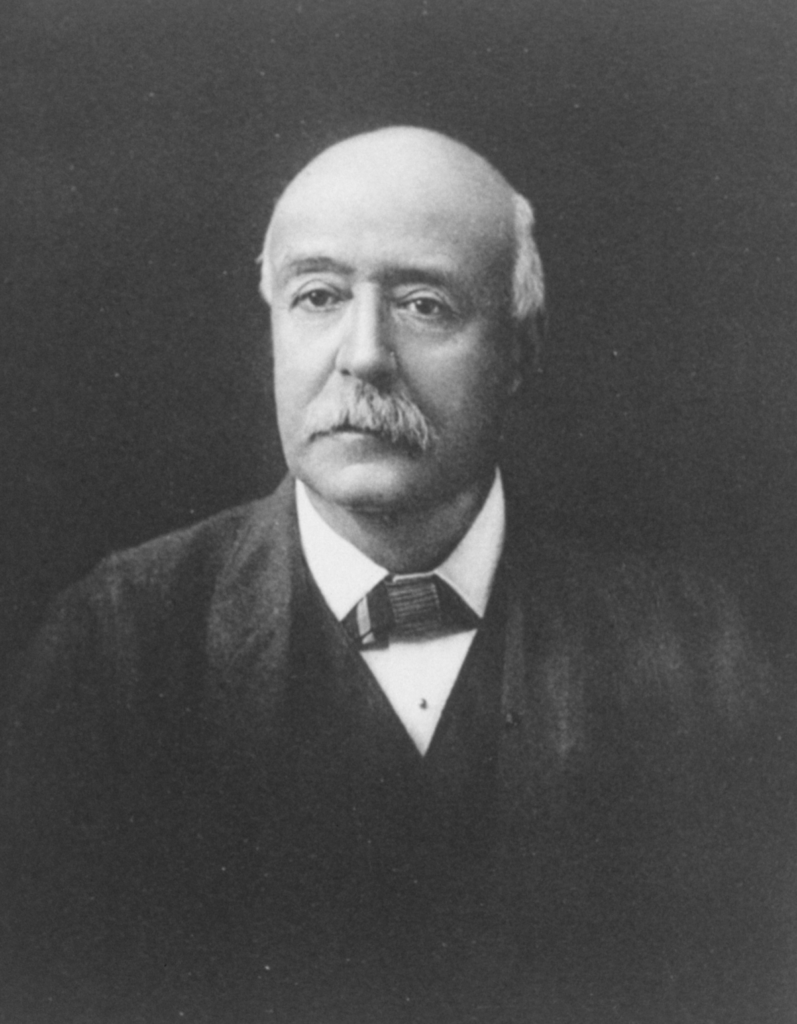

The clash over Darwin’s species theory was partly one between empiricism, as represented by Darwin’s superbly documented Origin of Species, and the idealist or creationist natural science dominant before then. Louis Agassiz, the Swiss-born naturalist who became the leading light of American science after moving to the United States in 1846, offered a particularly seductive articulation of creationist theory. He held huge audiences spellbound as he explained how nature’s patterned complexity could only have sprung from a single, divine intelligence. A species, he said, was “a thought of God.” His elegant description made him a giant of American science, the director of Harvard’s new Museum of Comparative Zoology, and a man of almost unrivaled fame.

But the publication of Origin, in 1859, confronted Agassiz’s idealist creationism with an empirically robust naturalistic description of species origin. Though Agassiz opposed Darwin’s theory vigorously, his colleagues increasingly took Darwin’s view, and by 1870, Louis Agassiz was no longer taken seriously by his peers. He could hardly have fallen further.

A Son

Louis’s only son, Alexander, came of age watching this fall. Smart and careful as child and man—he began his scientific career as an assistant at the Museum of Comparative Zoology and would manage it after his father died—Alexander seemed determined to avoid his father’s excesses. Where Louis was profligate, Alexander was frugal. Where Louis was expansive and extroverted, Alex was reserved and liked to work in private. And where Louis favored a creationist theory based on speculation, Alex preferred the empirical approach established by Darwin.

By the age of 35, Alexander Agassiz had created a happy life. He loved his work at the museum, his wife and three children, and by investing in and for 18 months managing a copper mine in Michigan, he had made himself quite rich. Yet his luck changed in 1873. Louis, then 63, died of a stroke two weeks before Christmas. Ten days later, Alex’s wife, Anna Russell Agassiz, died of pneumonia.

Wanderings and Reefs

Devastated by this double blow, Alex spent three years mostly traveling, mortally depressed. He felt able to “get back in harness,” as he put it, only when, in 1876, he engaged the coral reef problem. How did these great structures, built from the skeletons of animals that could grow only in shallow water, come to occupy platforms rising from the ocean’s depths? Naturalists had discerned in the early 1800s how corals grew, but the genesis of their underlying platforms remained obscure.

The prevailing explanation, first offered in 1837, held that coral reefs formed on subsiding islands. The coral first grew along shore, forming fringing reefs. As the island sank and lagoons opened between shore and reef, fringing reef became barrier reef. When the island sank out of sight, barrier reef became atoll. Thus this subsidence theory, as it was known, explained all main reef forms.

Alex, drawn to this problem by his friend Sir John Murray, a prominent Scottish oceanographer, thought the subsidence theory was just a pretty story. The theory rested on little other than the reef forms, while considerable evidence, such as the geology of many islands and most reef observations made during the mid-1800s, argued against it. Now Murray, who had just returned from a five-year oceanographic expedition aboard the HMS Challenger, told Alex of an alternative possibility. Murray had discovered that enough plankton floated in tropical waters to create a rain of planktonic debris that, given geologic time, could raise many submarine mountains up to shallows where coral reefs could form.

Alex immediately liked this idea, for it rose from close observation rather than conceptual speculation and relied on known rather than conjectural forces. Inspired for the first time since his wife’s death three years before, he began designing an extensive field research program to prove it.

There was only one problem: the person who had authored the subsidence theory was Charles Darwin.

Thirty Years of Fieldwork

Darwin had posited the subsidence theory as soon as he returned from the Beagle voyage in 1837. Like his evolution theory, it was a brilliant synthesis that explained many forms as the result of incremental change. But it did not rest on the sort of careful, methodical accumulation of evidence that underlay his evolutionary theory. Darwin conceived it before he ever saw a coral reef and published it when he’d seen only a few.

Yet the theory explained so much that it had launched Darwin’s career. Since then, of course, Darwin had developed his evolution theory, destroyed Louis’s career, and become the most renowned and powerful man in science. Alex knew he was courting trouble when he decided to champion an alternate theory. But he couldn’t resist such an enticing problem. And he firmly believed that Darwin had muffed it.

Alex spent much of the next 30 years collecting evidence. He developed a complicated and nuanced theory holding that different forces, primarily a Murray-esque accrual, erosion, some uplift, and occasionally some subsidence, combined in different ways to create the world’s different reef formations. He found evidence in every major reef formation on the globe. And so as the century ended, an Agassiz again faced Darwin (or Darwin’s legacy, for Darwin had died in 1882). Only this time the Agassiz held the empirical evidence and Darwin the pretty story.

Yet Alex hesitated to publish, even after he completed his fieldwork in 1903. Every year, Murray would ask Alex about the reef book. Every year Alex would say the latest draft hadn’t worked, but that he had found a better approach and would soon finish.

The last time he told Murray this was in 1910, when they met in London before Alex sailed home to the U.S. after a winter in Paris. On the fifth night out of Southampton, he died in his sleep. Murray, hearing the news by cable a couple days later, was much aggrieved—and stunned to hear what followed. A thorough search had found no sign of the coral reef book. It was, Alexander’s son George later wrote, “an excellent example of his habit of carrying his work in his head until the last minute.”

One Irony Among Many

The coral reef debate didn’t end until 1951, when U.S. government geologists surveying Eniwetok, a Marshall Islands atoll, prior to a hydrogen bomb test there, finally drilled deep enough to resolve the mystery. If Darwin was right about reefs accumulating atop their sinking foundations, the drill should pass through at least several hundred feet of coral before hitting the original underlying basalt. If Agassiz was right, the drill would go through a relatively thin veneer of coral before hitting basalt or marine limestone.

It speaks of the power of Alexander’s work that the reef expert directing the drilling, Harry Ladd, expected to prove Agassiz right. But the power of Darwin’s work was such that as the drill spun deep, it passed through not a few dozen or even a few hundred feet, but through some 4,200 feet of coral before striking basalt. Darwin was right, Agassiz wrong.

How did Alex miss this? In retrospect, geologists can identify various observational mistakes Alexander made. But Alex’s bigger problem was his singular place in the profound changes science underwent in the 1800s. Natural science in particular was struggling to define an empirical theoretical method. Alex played by the rules that most scientists, including Darwin, swore to: a Baconian inductivism that built theory atop accrued stacks of observed facts.

In reality, most scientists come to their theories through deductive leaps, then try to prove them by amassing evidence. A theory’s value rests not on its genesis, but on its proof. Today this is accepted and indeed codified as the “hypothetico-deductive method,” and its resulting theories are considered empirical as long as their proof lies in replicable evidence. But in Alex’s day, when pretty stories built on leaps of imagination spoke of reactionary creationism rather than creative empiricism, such theorizing was called speculation, and it was a four-letter word.

Alexander Agassiz was keenly sensitive to the dangers of such work. Yet his singular position fated him to take up a question that not only lay beyond the tools of his time, but which trapped him in the era’s most confounding difficulties of method and philosophy. He sought a solution that belonged to another age.

About the Author

David Dobbs is author of Reef Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz, and the Meaning of Coral, from which this lecture is drawn. You can find more of his work at daviddobbs.net.