Advancing the cancer research started by Casare Maltoni, the late Italian oncologist who advocated for industrial workplace safety.

Published August 1, 2002

By Fred Moreno, Dan Van Atta, Jill Stolarik, and Jennifer Tang

For decades, the “canary in the coal mine” approach has been used to test for potential carcinogens. Standing in for humans, mice and rats have ingested or been injected with various chemicals to help toxicologists determine if the substances would induce cancers. In the end, autopsy revealed whether the lab animals had developed tumors.

Today, new approaches are emerging. They stem from a variety of tools that are evolving from advances in molecular biology, microbiology, genomics, proteomics, novel animal models of carcinogenesis and computer technology.

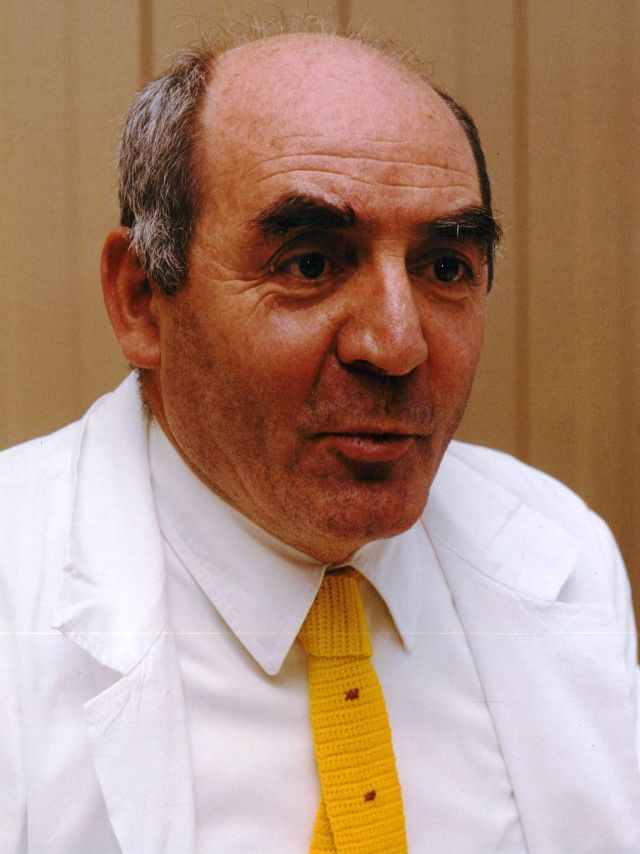

These tools and approaches were the focus of an April conference commemorating the work of Italian researcher Cesare Maltoni, who died January 21. Renowned for his research on cancer-causing agents in the workplace, Maltoni was the first to demonstrate that vinyl choloride produces angiosarcomas of the liver and other tumors in experimental animals. Similar tumors later were found to be occurring among industrial workers exposed to vinyl chloride.

Maltoni also was the first to demonstrate that benzene is a multipotential carcinogen that causes cancers of the zymbal gland, oral and nasal cavities, the skin, the forestomach, mannary glands, liver, and hemolymphoreticular systems, i.e. leukemias.

Sponsored by the Collegium Ramazzini, the Ramazzini Foundation, and the National Toxicology Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the meeting was organized by The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy).

Measuring More Than Pathological Changes

After reviewing the contributions of Maltoni and David Rall, an American giant in the same field, as well as providing an update on ongoing research in their respective groups, the speakers and attendees discussed the future of carcinogenesis testing. While new tools will not replace bioassays, most noted, they will make it possible to measure more than simply the pathological changes seen through the microscope.

J. Carl Barrett, head of the Laboratory of Biosystems and Cancer at the National Cancer Institute, cited four recent developments that are fundamentally changing the research to identify risk factors and biological mechanisms in carcinogenesis.

The four developments are: new animal models with targeted molecular features – such as mice bred with a mutated p53 oncogene – that make them very sensitive to environmental toxicants and carcinogens; a better understanding of the cancer process; new molecular targets for cancer prevention and therapy; and new technologies in genomics and proteomics.

New technologies in cancer research, like gene expression analyses, are revealing that cancers that look alike under the microscope are often quite different at the genetic level. “Once we can categorize cancers using gene profiles,” Barrett said, “we can determine the most effective chemotherapeutic approaches for each – and we may be able to use this same approach to identify carcinogenic agents.”

A Robust Toxicology Database

A related effort – to link gene expression and exposure to toxins – has recently been launched at the NIEHS. The newly created National Center for Toxicogenomics (NCT) focuses on a new way of looking at the role of the entire genome in an organism’s response to environmental toxicants and stressors. Dr. Raymond Tennant, director of the NCT, said the organization is partnering with academia and industry to develop a “very robust toxicology database” relating environmental stressors to biological responses.

“Toxicology is currently driven by individual studies, but in a rate-limited way,” Tennant said. “We can use larger volumes of toxicology information and look at large sets of data to understand complex events.” Among other benefits, this will allow toxicologists to identify the genes involved in toxicant-related diseases and to identify biomarkers of chemical and drug exposure and effects. “Genomic technology can be used to drive understanding in toxicology in a more profound way,” he said.

Using the four functional components of the Center (bioinformatics, transcript profiling, proteomics and pathology), Tennant believes that the NCT will be able “to integrate knowledge of genomic changes with adverse effects” of exposure to toxicants.

Current animal models of carcinogenesis are unable to capture the complexity of cancer causation and progression, noted Dr. Bernard Weinstein, professor of Genetics and Development, and director emeritus of the Columbia-Presbyterian Cancer Center.

Multiple factors are involved in the development of cancer, Weinstein said, making it difficult to extrapolate risk from animal models. Among the many factors that play a role in cancer causation and progression are “environmental toxins such as cigarettes, occupational chemicals, radiation, dietary factors, lifestyle factors, microbes, as well as endogenous factors including genetic susceptibility and age.”

Gene Mutation and Alteration

By the time a cancer emerges, Weinstein added, “perhaps four to six genes are mutated, and hundreds of genes are altered in their pattern of expression because of the network-like nature and complexity of the cell cycle. The circuitry of the cancer cell may well be unique and bizarre, and highly different from its tissue of origin.”

Research over the past decade has underscored the role that microbes play in a number of cancers: the hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses in liver cancer along with cofactors alcohol and aflatoxin; human papilloma virus and tobacco smoke in cervical cancer; and Epstein Barr virus and malaria in lymphoma, said Weinstein. Microbes are likely to be involved in the development of other kinds of cancer as well, he speculated. “Microbes alone cannot establish disease, they need cofactors. But this information is important from the point of view of prevention, and these microbes and their cofactors are seldom shown in rodent models.”

When thinking of ways to determine the carcinogenicity of various substances, he concluded, “we have to consider these multifactor interactions, and to do this we need more mechanistic models” of cancer initiation and progression.

Christopher Portier, a mathematical statistician in the Environmental Toxicology Program at the NIEHS, is working to make exactly this type of modeling more widespread. He stressed the importance and advantages of complex analyses of toxicology data using a mechanism-based model – or “biologically based data.”

This model includes many more factors than just length of exposure and time till death of the animal. It can incorporate “the volume of tumor, precursor lesions, dietary and weight changes, other physiological changes, tumor location and biological structure, biochemical changes, mutations,” Portier said, and give a more complete picture of the processes that occur when an organism is exposed to a toxicant.

New Analytical and Biological Tools

With biologically based models, researchers would link together a spectrum of experimental findings in ways that allow them to define dose-response relationships, make species comparisons, and assess inter-individual variability, Portier said. Such models would allow researchers to quantify the sequence of events that starts with chemical exposure and ends with overt toxicity. However, he said “each analysis must be tailored to a particular question. They are much more difficult computationally and mathematically than traditional analyses, and require a team-based approach.

“Toxicology has changed,” Portier continued. “We now have new analytical and biological tools – including transgenic and knockout animals, the information we’ve gained through molecular biology, and high through-put screens. We need to link all that data together to predict risk, then we need to look at what we don’t know and test that.”

While most speakers focused on the future benefits of up and coming technologies and concepts, Philip Landrigan, director of the Mount Sinai Environmental Health Sciences Center at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, reminded the group of the work on the ground that still needs to be accomplished. “We’ve made breathtaking strides in our understanding of carcinogens and cancer cells,” he said. “I am struck, though, by the divide in the cancer world – the elegance of the lab studies, but our inefficiency in applying that knowledge to cancer prevention.”

Thorough Testing Needed

One of the problems confronting researchers is the vast number of substances that are yet to be tested. About 85,000 industrial chemicals are registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for use in the United States. Although some 3,000 of these are what the EPA calls high-production-volume chemicals, Landrigan said, “only 10 percent of these have been tested thoroughly to see the full scope of their carcinogenic potential, their neurotoxicity and immune system effects.”

Landrigan also discussed other troubling issues. For example: Children, the population most vulnerable to the effects of toxins, are only rarely accounted for in testing design and analysis, he said, and the United States continues to export “pesticides, known carcinogens, and outdated factories to the Third World.” Landrigan said he believes the world’s scientific community needs to address these issues.

At the conclusion of the conference, Drs. Kenneth Olden and Morando Soffritti signed an agreement formalizing an Institutional Scientific Collaboration between the Ramazzini Foundation and the NIEHS in fields of common interest. Priorities of the collaboration will include: carcinogenicity bioassays on agents jointly identified; research on the interactions between genetic susceptibility and exogenous carcinogens; biostatistical analysis of results and establishment of common research management tools; and molecular biology studies on the basic mechanisms of carcinogenesis.

Detailed information presented in several papers will be included in the proceedings of the conference, to be published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences later this year.

Also read: From Hypothesis to Advances in Cancer Research