While there have been major advances in biomedical research in recent years, this has also presented scientists with new challenges.

Published April 1, 2002

By Rosemarie Foster

In Boston’s historic Fenway neighborhood, just beyond Back Bay, each spring heralds an annual ritual of renewed life. The Victory Gardens come abuzz with activity and abloom with burgeoning buds. Canoeists charge to the nearby Charles River. And sluggers at Fenway Park swing from their heels, cast in the spell of a 37-foot-high wall called the “Green Monster” that rises beyond the tantalizingly shallow left field.

Much history has been recorded inside the boundaries of Boston’s legendary baseball venue. But the seeds of a different kind of history –– that of 21st century biomedical science –– are being planted in the Fenway district this spring. Two important new scientific research facilities being built –– an academic addition to the Harvard Medical School and a commercial laboratory planned by pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co., Inc. –– will no doubt help shape biomedical advances for decades to come.

Merck is constructing its 11th major research site –– Merck Research Laboratories-Boston –– in the heart of the district. The company hails the facility as a multidisciplinary research center devoted to drug discovery. Covering an area of 300,000 square feet supporting 12 stories above ground and six stories below, Merck hopes its state-of-the-art structure will lure some 300 investigators to pursue studies within its walls. The building is scheduled for completion in 2004.

Harvard’s own new 400,000-squarefoot research building is under construction just 50 feet from the Merck site. With a design that fosters interactions between scientists, Harvard’s new facility will build on the university’s commitment to high throughput technologies. It’s expected to be operational in 2003.

The Interrelationship of Academic and Commercial Research

Although the two facilities are some way from completion, they’ve already exposed one of the major issues –– the interrelationship of academic and commercial research –– that continue to challenge biomedicine. Because of its close proximity to the Harvard Medical School, some scientists fear the new Merck facility may create some tension between nearby university investigators and industry researchers.

“The Merck laboratories, as a commercially driven research organization, may pay better salaries, have better equipment, have a better capacity for high-throughput screening and medicinal chemistry, and have other facilities that an academic medical center typically does not have available,” explained Charles Sanders, MD, former Chairman and CEO of Glaxo, Inc. and former Chairman of the Board of The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy). “Whether this will create a source of problems for Harvard and its scientists remains to be seen. On the other hand, it could be a great resource if the academic-industrial relationship is managed well.”

Such tensions are likely to continue as emerging new trends in biomedical research offer investigators both greater opportunities and increasing challenges. Academia and industry are partnering in ways they never have before. New high-throughput technologies are generating more data than previously thought possible. And scientists from a variety of fields must now cross interdisciplinary lines –– an approach some dub “systems biology” –– to make significant progress in conquering such diseases as cancer and AIDS.

New Approaches

A number of other biomedical research organizations have already set the stage for the new approaches to be incorporated into the Merck and Harvard facilities. In 1998, Stanford University launched an enterprise called “Bio-X” to facilitate interdisciplinary research and teaching in the areas of bioengineering, biomedicine and the biosciences. In January 2000, Leroy Hood, MD, PhD, created the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle –– a research Environment that seeks to integrate scientists from different fields; biological information; hypothesis testing and discovery science; academia and the private sector; and science and society.

Some say it’s the “golden age” of biomedical investigation. The evolution that has led to this new age was the subject, along with related issues, of a gathering of biomedical researchers at the Academy last April. Hosted by the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR), the symposium was called The Biotechnology Revolution in the New Millennium: Science, Policy, and Business.

“This meeting did an excellent job of showing how the nature of biomedical research has changed in the last 25 years,” explained Rashid Shaikh, PhD, the Academy’s Director of Programs, “not just quantitatively, in the amount of information we can generate, but also qualitatively, in the way the work is done. And this is a rapidly evolving process.”

A Quickened Pace

Much of the recent change in biomedical research is the result of a pace of investigation that has accelerated during the last quarter century – thanks in large part to recombinant DNA technology created in the 1970s. This Technology received a boost of support when the war on cancer was declared that same decade.

“Once recombinant DNA technology appeared, there was an enormous shift in molecular biology,” said David Baltimore, PhD, Nobel laureate and President of the California Institute of Technology, who chaired the amfAR symposium. “From a purely academic enterprise, it turned into one that had enormous implications for industry.”

Early on, the infant biotechnology enterprise focused on cloning to manufacture drugs, added Baltimore. The cloning was employed in the search for targets for a new generation of small molecule drugs. The need for chemical libraries soon developed, followed by a demand for high-throughput screening technologies. Add to that the wealth of information gleaned from the Human Genome Project.

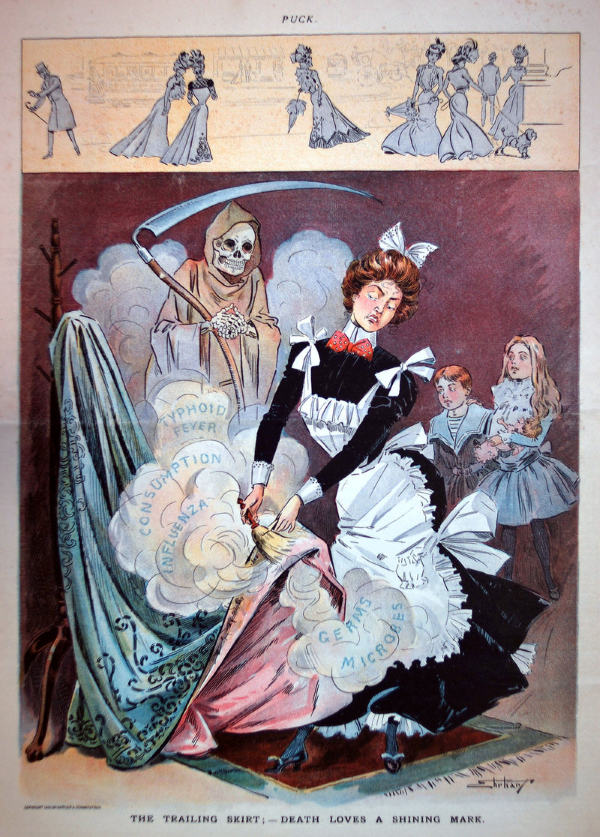

Today investigators have more data than they ever did before. With the advent of high-throughput screening technologies, they also have speedier methods at their disposal to generate even more data. The nascent field of proteomics is expected to propel biomedicine even further. But with this heightened pace of research come new challenges.

For one thing, data are being generated faster than they can be analyzed and understood. Novel technologies have spawned a new field called bioinformatics: the analysis of all the data generated in the course of biomedical investigation. “We used to be able to look at the expression of one gene at a time,” said Shaikh. “But thanks to technologies (such as microarray systems), we can now analyze the expression of thousands of genes at once.”

High Demand, Low Supply of Bioinformatics Professionals

Bioinformatics professionals –– those who perform the data analysis –– are high in demand but short in supply, however, creating a problem for some research centers. Because they are so hard to come by, some institutions are sharing bioinformatics staff until a new generation of professionals can be educated and enter the workforce.

A second question that comes to mind is, “Who owns all these new data?” Is it the property of the individual researcher? The university he or she works for? The pharmaceutical company that sponsored the work or, if the studies were supported by public funds, is it the public?

Ownership issues apply to electronically published data as well. “Some of the data get published and made available to the scientific community, but some do not,” said Donald Kennedy, PhD, Editor-in-Chief of Science and President Emeritus of Stanford University. “Now that all data are stored electronically, there are major changes afoot in how data can be accessed in useful and efficient ways. But there are major unresolved questions regarding who owns the data: Do the publishers? Do the investigators?” These significant legal and policy issues will need to be resolved and, given the current rapid pace of study, resolved quickly.

A Blurred Line

In Europe, industrial support for universities has been an accepted and uncomplicated practice since the late 1800s, and this relationship continues to this day. But the relationship between academia and industry in the United States has had a quite different history, noted Charles Sanders.

As the American pharmaceutical industry began to develop in the last quarter of the 19th and early part of the 20th centuries, a relationship akin to the European model began to flower. By the early 1930s, however, the relationship between academia and industry in America began to sour. Disagreements arose over research discoveries and credit; there were disputes regarding the unauthorized use of pictures of some scientists in advertisements, implying endorsement of certain companies and products.

After World War II, the climate began to improve. With the advent of biotechnology in the 1970s, relations flourished even more, as witnessed by the founding of companies such as Genentech and Biogen by academic scientists. In addition, there are now countless examples of companies that support research programs at universities under a variety of arrangements.

On the face, these associations appear positive, because there is now a wealth of new sources for investigators to turn to for research funding. But these new opportunities also present certain challenges.

One of the most obvious concerns when industry supports a researcher is the investigator’s objectivity. Conflict of interest issues may arise. “Academic scientists who work with industry are generally very careful to retain their objectivity, yet appearances sometimes don’t allow that,” said Sanders. “The industry has to be very careful and make sure that its academic collaborators totally protect their objectivity and reputation.”

Intellectual Property Issues

Secondly, when academia partners with industry, intellectual property issues again surface. How does one determine who benefits financially from a research endeavor that goes on to produce a profitable product, such as a successful drug? How much does the scientist receive, and the university he or she works for, and how is that money used? “Academic institutions have become more sophisticated, and the scientists and organizations are demanding an ever larger part of the pie from their discoveries,” said Sanders.

Donald Kennedy noted that in industry-supported investigations a large proportion of research results that are of potential public value may be locked up in proprietary protections. Students at Yale University and the University of Minnesota recently demonstrated, for example, that their universities were collecting royalties on drugs that can benefit people suffering from HIV/AIDS in developing countries.

“Although the royalty slice of the drug price is minuscule in proportion to total revenues, it is very unattractive money to the students, and they make a passionate case,” said Kennedy. “Ironically, everybody involved in this process thought they were doing something good, and in a way everyone was. But this is the kind of problem that emerges when proprietary interests mix with the basic research function in a nonprofit institution.”

A Mixing of the Minds

Scientists are increasingly of the opinion that an integrated approach to biological investigation is essential for significant, meaningful progress to occur. This “systems approach” is bringing together biologists, chemists, physicists, engineers and computer scientists to coordinate research efforts and interpret the resulting data.

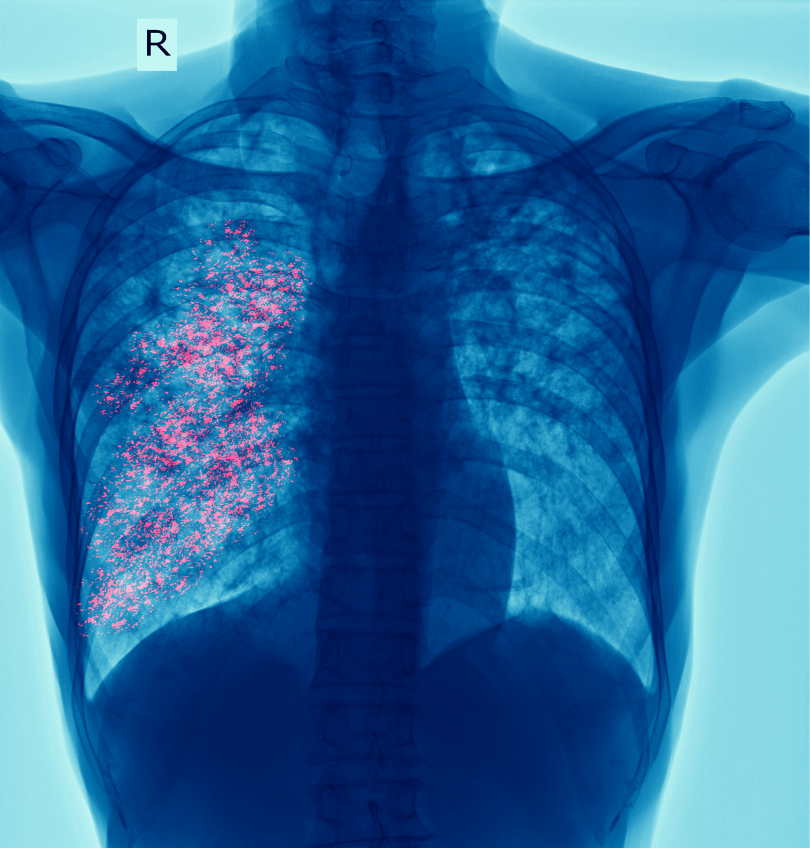

Such an approach is critical for understanding the inner workings of cells and how their functions go awry to create diseases such as cancer. The AIDS virus has proven to be an excellent model supporting the need for a multidisciplinary approach: When it was first discovered in the early 1980s, it was assumed that a vaccine was just around the corner. But that has obviously not been the case.

“It turned out that HIV was more difficult than anybody imagined, smarter and slipperier,” said David Baltimore. The cleverness of the virus has sent researchers back to their lab benches. Only by gathering together immunologists, structural biologists, biochemists and experts from other fields can we determine exactly what the virus does to the human immune system to deliver its lethal blow.

Is “Systems Biology” the Way to Go?

Not all investigators are convinced that “systems biology” –– as Hood describes it –– is the way to go. Many established researchers, for example, are used to working alone in conventional academic settings. “Traditional academic institutions have a difficult time fully engaging in systems biology, given their departmental organization and their narrow view of education and cross-disciplinary work,” explained Leroy Hood, President and Director of the Institute for Systems Biology. “The tenure system presents another serious challenge: Tenure forces people at the early stages of their careers to work by themselves on safe kinds of problems. However, the heart of systems biology is integration, and that’s a tough challenge for academia.”

“Specialization is often the enemy of cooperation,” added David Baltimore. “There are deep and important relationships between biology and other disciplines. To understand biology, we need chemists, physicists, mathematicians and computer scientists, as well as other people who can think in new ways.”

Future Challenges

Despite the presence of these as yet unresolved issues, biomedical research continues to hurdle forward, shedding light on the inner workings of organisms and yielding insights that will undoubtedly impact health and medicine. “The true applications (of biotechnology) to patient care have not really matured yet,” said Rashid Shaikh. “But there’s every reason to believe that we’re going to make very rapid progress in that direction.”

In addition to the challenges above, other issues include:

• Gathering political support. Although the budget of the National Institutes of Health has seen a significant increase in the last several years, other science-related agencies may not be as fortunate. “These agencies’ research budgets have not seen an increase, and we must pay attention to them,” said Baltimore.

• Educating the public. Hood touched on the distrust the public can have regarding science. “I am deeply concerned about society’s increasingly suspicious and often negative reaction to developments in science,” he said. “I sense an enormous uncertainty, discomfort and distrust. There is a feeling that we’re just making everything more expensive and more complicated. How do we advocate for opportunities in science? We have to be truthful about the challenges as well.”

• Educating today’s students. One of the best ways to garner support for a systems approach to biological investigation is to start educating students this way today. In Seattle, for example, the Institute for Systems Biology has pioneered innovative programs in an effort to transform the way science is taught in public schools.

“This is truly the golden age of biology,” said Sanders. There are unprecedented numbers of targets and compounds, for example. Research and development are very expensive, but funds will be available in abundance.

The Public’s Expectations

Still, he added, we need to handle the expectations of the public, which can be unrealistic when it comes to the speed with which basic science findings will result in new therapies. And academic institutions have to balance a commitment to both basic and translational research.

“Thousands of flowers will continue to bloom, driven by the lure of discovery and the opportunity to improve human health,” added Sanders. “Though not linear, the process is very creative, entrepreneurial, and clearly reflective of the American free enterprise system.”

Also read:Building the Knowledge Capitals of the Future

About the Author

Rosemarie Foster is an accomplished medical freelance writer and vice president of Foster Medical Communications in New York.