Much of German physician Robert Koch’s research on tuberculosis is more relevant than ever as this contagious disease is reemerging globally.

Published January 1, 2002

By Fred Moreno, Dan Van Atta, Jill Stolarik, and Jennifer Tang

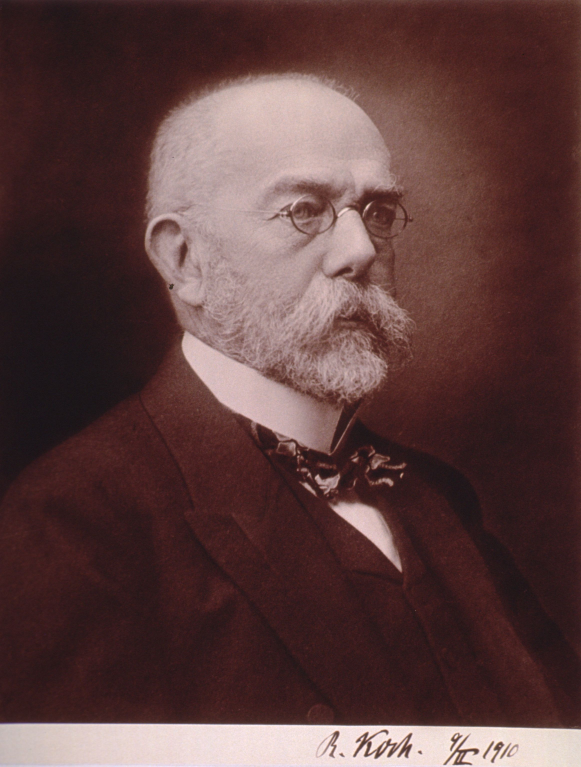

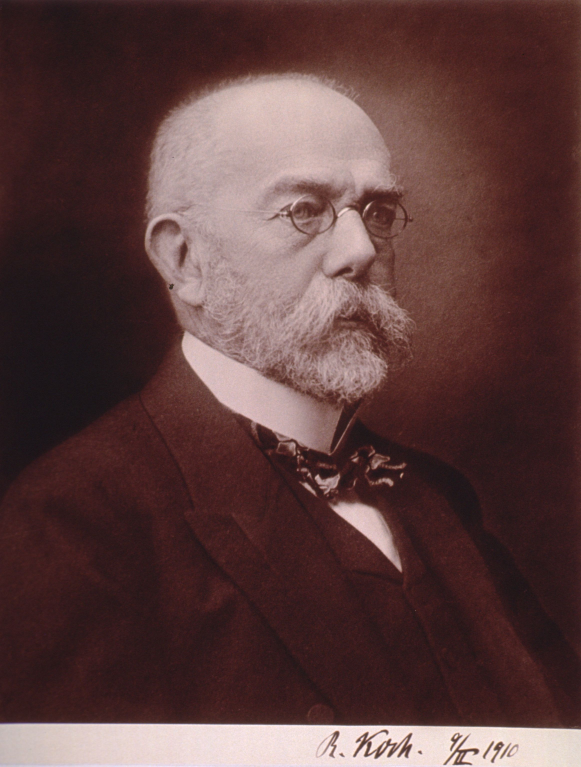

On March 24, 1882, a thin, near-sighted German physician named Robert Koch delivered his latest research paper to an evening meeting of the Physiological Society of Berlin. His audience was attentive. Koch had already made a name for himself by identifying the cause of a leading pathogenic killer of cattle –– a disease called anthrax.

Koch, a country practitioner in Wollstein, Posen, who devoted much time to microscopic studies of bacteria, also had developed a way to dry and strain the anthrax bacterium for examination under a microscope, and a way to grow it in a culture. His techniques of bacteriological culture continue in use around the world, most recently as a tool in conclusively diagnosing anthrax in the human victims of 21st century terrorists.

But anthrax was not the subject of Koch’s paper that evening. Instead, he spoke of an even more dreaded disease that had long plagued humanity: a menace that had so consumed its victims that it was commonly called death by “consumption.” Koch presented to the attending physicians and scientists the first convincing evidence that tuberculosis (TB) is caused by an infectious bacterium.

Ironically today, while world attention has recently focused on the deadly potential of anthrax spores used as bio-weaponry, the global threat from multi-drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is perhaps as great as the TB challenge posed that evening in 1882 –– 13 years before William Conrad Roentgen discovered X-rays.

The Present TB Threat

This present TB threat is conveyed in compelling detail in a new McGraw-Hill book: Timebomb –– The Global Epidemic of Multi-Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis, by Dr. Lee B. Reichman (M.D., M.P.H.) and Janice Hopkins Tanne, an award-winning science and medical writer, and member of The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy). Evidence the book presents in support of its chilling title is based on a lifetime of experience and personal observation by Reichman, executive director of the New Jersey Medical School National Tuberculosis Center and former director of the New York City Health Department’s Bureau of Tuberculosis.

Reichman and Tanne build a clear and convincing case in support of the World Health Organization (WHO) and allied public health groups that are working to combat the global MDR-TB threat.

Estimates say one-third of the world’s population –– about 2 billion people –– are currently infected with TB. The disease often remains latent in the lungs of unknowing victims for years, usually manifesting if and when the victim’s immune system is stressed (which is one reason TB is a leading cause of death among HIV/AIDS sufferers).

An Airborne Threat

Each year, another 8.4 million people actually become ill with TB, and 2 to 3 million people die of TB. Because TB bacteria readily fly through the air, as when an afflicted person coughs, it’s estimated that each victim will infect 10 to 20 or more other people –– in whom the disease will likely remain latent, creating the potential “timebomb” effect.

Tuberculosis has become resistant to many of the drugs previously used to cure it, because of incorrect prescribing or failure to make sure the patient completes treatment. It will be many years before effective new drugs are readily available.

The WHO-approved direct observation therapy (DOTS) is a multi-drug regimen that can save the lives of MDR-TB patients if started early enough and the patient cooperates. But successful treatment is very costly, requiring at least several months of carefully monitored therapy.

Malnutrition and poor living conditions help create MDRTB “factories” in some of the world’s most impoverished populations –– such as in Africa, Peru and the former Soviet states. Timebomb describes in gruesome detail Reichman’s visits –– along with teams of experts, including Academy member Dr. Barry Kreiswirth, director of the Public Health Research Institute’s TB Center –– to the overcrowded gulags, or prisons, of the former Soviet Union.

Despite reforms, an MDR-TB epidemic is raging in the Post Cold War prisons of Russia today. Timebomb explores in great depth the economic, cultural and geo-political problems that continue to impede progress.

A Decades-long Process

A TB vaccine called BCG (bacille Calmette-Guérin, named for the French scientists who developed it) was widely used in the 20th century and is still one of six vaccines in the WHO’s expanded program of immunizations. Active TB has been found in persons who have received BCG, however, and the Timebomb authors say there’s no proof the vaccine is effective. While there is a great deal of scientific interest in developing an effective vaccine, they say the process will likely take decades.

Timebomb’s publication is timely not only because of the attention that recent bio-terrorist threats have focused on bacteriological agents, but also because March 24, 2002 –– designated World TB Day –– will honor Koch’s findings about M. tuberculosis with outreach activities supported by organizations in more than 200 countries. They include the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, the World Health Organization, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the American Lung Association.

“One-seventh of all human beings die of tuberculosis,” Koch, told the Berlin gathering on that evening, almost 120 years ago. “If one considers only the productive, middle age groups, tuberculosis carries away one-third and often more of these.” For his discovery of the tuberculosis bacterium and the tuberculin test, Koch was awarded the 1905 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.

Despite the genius of Robert Koch and the dedicated work of countless scientists and physicians who have come after him, the MDR-TB threat that Reichman and Tanne so thoroughly elucidate is just as serious today.