Overview

The human body regenerates itself constantly, replacing old, worn-out cells with a continuous supply of new ones in almost all tissues. The secret to this perpetual renewal is a small but persistent supply of stem cells, which multiply to replace themselves and also generate progeny that can differentiate into more specialized cell types. For decades, scientists have tried to isolate and modify stem cells to treat disease, but in recent years the field has accelerated dramatically.

A major breakthrough came in the early 21st century, when researchers in Japan figured out how to reverse the differentiation process, allowing them to derive induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from fully differentiated cells. Since then, iPS cells have become a cornerstone of regenerative medicine. Researchers can isolate cells from a patient, produce iPS cells, genetically modify them to repair any defects, then induce the cells to form the tissue the patient needs regenerated.

On April 26, 2019, the New York Academy of Sciences and Takeda Pharmaceuticals hosted the Frontiers in Regenerative Medicine Symposium to celebrate 2019 Innovators in Science Award winners and highlight the work of researchers pioneering techniques in regenerative medicine. Presentations and an interactive panel session covered exciting basic research findings and impressive clinical successes, revealing the immense potential of this rapidly developing field.

Symposium Highlights

- New cell lines should reduce the time and cost of developing stem cell-derived therapies.

- The body’s microbiome primes stem cells to respond to infections.

- iPS cell-derived therapies have already treated a deadly genetic skin disease and age-related macular degeneration.

- Polyvinyl alcohol is a superior substitute for albumin in stem cell culture media.

- A newly isolated type of stem cell reveals the stepwise process driving early embryo organization.

Speakers

Shinya Yamanaka

Kyoto University

Shruti Naik

New York University

Michele De Luca

University of Modena and Reggio Emilia

Masayo Takahashi

RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research

Hiromitsu Nakauchi

Stanford University and University of Tokyo

Brigid L.M. Hogan

Duke University School of Medicine

Emmanuelle Passegué

Columbia University Irving Medical Center

Hans Schöler

Max Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine

Austin Smith

University of Cambridge

Moderator: Azim Surani

University of Cambridge

Sponsors

Recent Progress in iPS Cell Research Application

Speakers

Shinya Yamanaka

Kyoto University

Highlights

- Current protocols for using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells clinically are slow and expensive.

- HLA “superdonor” iPS cell lines can be used to treat multiple patients, reducing costs.

- A unique academic-industry partnership is helping iPS cell therapies reach the clinic.

Faster, Cheaper, Better

Shinya Yamanaka of Kyoto University, gave the meeting’s keynote presentation, summarizing his laboratory’s recent work using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells for regenerative medicine. The first clinical trial using iPS cells to treat age-related macular degeneration started five years ago. In his clinical trial, physicians isolated somatic cells from a patient, then used developed culture techniques to derive iPS cells from them. iPS cells can proliferate and differentiate into any type of cell in the body, which can then be transplanted back into the patient. Experiments over the past five years have shown that this approach has the potential to treat diseases ranging from age-related macular degeneration to Parkinson’s disease.

However, this autologous transplantation strategy is slow and expensive. “It takes up to a year just evaluating one patient, [and] it costs us almost one million US dollars,” said Yamanaka. Before transplanting the differentiated cells, the researchers evaluated the entire iPS cell derivation and iPS cell differentiation processes, adding to time and cost. As another strategy, Yamanaka’s team is working on the iPS Cell Stock for Regenerative Medicine. Here, iPS cells are derived from blood cells of healthy donors, not the patients, and are stocked. The primary problem with this approach is the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system, which encodes multiple cell surface proteins. Each person has a specific combination of HLA genes, or haplotype, defining the HLA proteins expressed on their own cells. The immune system recognizes and eliminates any cell expressing non-self HLA proteins. Because there are millions of potential HLA haplotypes, cells derived from one person will likely be rejected by another.

The homozygous “superdonor” cell line has limited immunological diversity, allowing it to match multiple patients.

To address that, Yamanaka and his colleagues are collaborating with the Japanese Red Cross to develop “superdonor” iPS cells. These cells carry homozygous alleles for different human lymphocyte antigen (HLA) genes, limiting their immunological diversity and making them match multiple patients. So far, the team has created four “superdonor” cell lines, allowing them to generate cells compatible with 40% of the Japanese population. Those cells are now being used in clinical trials treating macular degeneration and Parkinson’s disease, with more indications planned.

“So far so good,” said Yamanaka, but he added that “in order to cover 90% of the Japanese population we would need 150 iPS cell lines, and in order to cover the entire world we would need over 1,000 lines.” It took the group about five years to generate the first four lines, so simply repeating the process that many more times isn’t practical.

Instead, Yamanaka hopes to take the HLA reduction a step further, knocking out most of the major HLA genes to generate cells that will survive in large swaths of the population. However, simply knocking out entire families of genes isn’t enough. Natural killer cells attack cells that are missing particular cell surface antigens, so the researchers had to leave specific markers in the cells, or reintroduce them transgenically. Natural killer and T cells from various donors ignore leukocytes derived from these highly engineered iPS cells, proving that the concept works. With this approach, just ten lines of iPS cells should yield a range of donor cells suitable for any human HLA combination. Yamanaka expects these gene-edited iPS cells to be available in 2020.

By 2025, Yamanaka hopes to announce “my iPS cell” technology. This technology will reduce the cost and time for autologous transplantation to about $10,000 and one month per patient.

While preclinical and early clinical trials on iPS cells have yielded promising results, the new therapies must still cross the “valley of death,” the pharmaceutical industry’s term for the unsuccessful transition and industrialization of innovative ideas identified in academia to routine clinical use. In an effort to make that process more reliable, Yamanaka and his colleagues have begun a unique collaboration with Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Japan’s largest drug maker. The effort involves 100 scientists, 50 each from the company and academic laboratories. The corporate researchers gain access to the latest basic science developments on iPS cell technology, while the academics can use the company’s cutting-edge R&D know-how equipment and vast chemical libraries.

In one project, the collaborators used iPS cells to derive pancreatic islet cells, and then encapsulated the cells in an implantable device to treat type 1 diabetes. The system successfully decreased blood glucose in a mouse model, and the team is now scaling up cell production to test it in humans in the future. Another effort identified chemicals in Takeda’s compound library that speed cardiomyocyte maturation, which the researchers are now using to improve iPS cell-derived treatments for heart failure. In a third project, the team has modified iPS cell-derived T cells to identify and attack tumors, again showing promising results in a mouse model.

Further Reading

Yamanaka

Fujimoto T, Yamanaka S, Tajiri S, et al.

Scientific Report. 2019; 9:6965.

Karagiannis P, Yamanaka S, Saito MK.

Application of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases.

Experimental Hematology. 2019;71:43-50.

Suga M, Kondo T, Imamura K, et al.

Stem Cell Research. 2019;36(101406).

The Winners’ Circle

Speakers

Shruti Naik

New York University

Michele De Luca

University of Modena and Reggio Emilia

Highlights

- Epithelial barriers must distinguish harmless commensal bacteria from dangerous pathogens.

- Mice lacking commensal bacteria exhibit defective immune responses.

- Inflammation causes persistent changes in epithelial stem cells, priming them for subsequent immune responses.

- Modified iPS cells can be used to cure a patient with a deadly genetic skin defect.

- A small population of self-renewing stem cells maintains human skin cells.

Sparring Partners

Shruti Naik, Early-Career Scientist winner of the 2019 Innovators in Science Award, discussed her work on epithelial barriers. These barriers, which include skin and the linings of the gut, lungs, and urogenital tract, exhibit nuanced responses to the many microbes they encounter. Injuries and pathogenic infections trigger prompt inflammatory responses, but the millions of harmless commensal bacteria that live on these surfaces don’t. How does the epithelium know the difference?

To ask that question, Naik first studied germ-free mice, which lack all types of bacteria. These animals have defective immune responses against pathogens that affect epithelia, so commensal bacteria are clearly required for developing normal epithelial immunity. Naik inoculated the germ-free mice with bacterial strains found either on the skin or in the guts of normal mice, then assessed their immune responses in those two compartments.

“When you gave gut-tropic bacteria, you were essentially able to rescue immunity in the gut but not the skin, and conversely when you gave skin-tropic bacteria, you were able to rescue immunity in the skin and not the gut,” said Naik. Even though the commensal bacteria caused no inflammation, they did activate certain T cells in the epithelia they colonized, apparently preparing those tissues for subsequent attacks by pathogens.

Next, Naik took germ-free mice inoculated with Staphylococcus epidermidis, a normal skin commensal bacterium, and challenged them with an infection by Candida albicans, a pathogenic yeast. The bacterially primed mice produced a much more robust immune response against the yeast infection than control animals that hadn’t gotten S. epidermidis. Naik confirmed that this immune training effect operates through the T cell response she’d seen before. “You essentially develop an immune arsenal to your commensals that helps protect against pathogens,” Naik explained, adding that each epithelial barrier requires its own commensal bacteria to trigger this response.

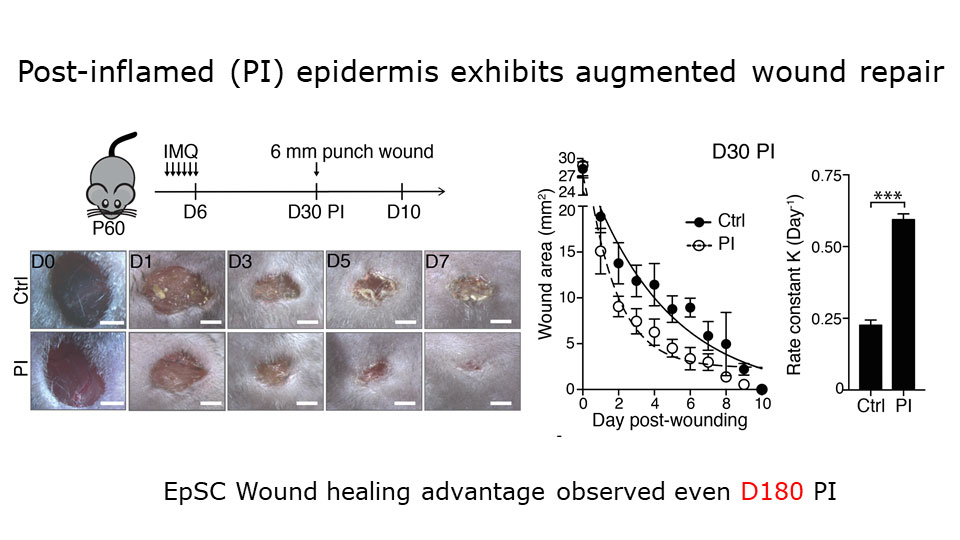

Augmented wound repair in post-inflammation skin reveals that naive and inflammation-educated skin stem cells respond differently to subsequent stresses.

The response to epithelial commensals is remarkably durable; Naik found that the skin T cells in the inoculated mice remained on alert a year after their initial activation. That led her to wonder whether non-hematopoietic cells, especially epithelial stem cells, contribute to immunological memory in the skin.

To probe that, Naik and a colleague used a mouse model in which the topical drug imiquimod induces a temporary psoriasis-like skin inflammation. By tracing the lineages of cells in the animals’ skin, the researchers found that epithelial stem cells expand during this inflammation, and then persist. Challenging the mice with a wound one month after the inflammation resolves leads to faster healing than if the mice hadn’t had the inflammation. Several other models of wound healing yielded the same result. The investigators concluded that naive and inflammation-educated skin stem cells respond differently to subsequent stresses.

Naik’s team found that inflammation causes persistent changes in skin stem cells’ chromatin organization. Using a clever reporter gene assay, they demonstrated that the initial inflammation leaves inflammatory gene loci more open in the chromatin, making them easier to activate after subsequent insults. “What was really surprising to us was that this change never fully resolved,” said Naik. Even six months after the acute inflammation, skin stem cells retained the distinct post-inflammatory chromatin structure and the ability to heal wounds quickly. This chronic ready-for-action state isn’t always beneficial, though. Naik noticed that the mice that had had the inflammatory treatment were more prone to developing tumors, for example.

In establishing her new laboratory, Naik has now turned her focus to another aspect of epithelial immunity: the link between immune responses and tissue regeneration. She looked first at a type of T cells found in abundance around hair follicles on skin. Mice lacking these cells exhibit severe delays in wound healing, apparently as a result of failing to vascularize the wound area. That implies a previously unknown role for inflammatory T cells in vascularization, which Naik and her lab are now probing.

Skin Deep

Michele De Luca, Senior Scientist winner of the 2019 Innovators in Science Award, has developed techniques for regenerating human skin from transgenic epidermal stem cells. Researchers first isolated holoclones, or cells derived from a single epidermal stem cell, over 30 years ago. These cells can be used to grow sheets of skin in culture for both research and clinical use, but scientists have only recently begun to elucidate how the process works.

The first stem cell-derived therapies tested in humans were for skin and eye burns, allowing doctors to regenerate and replace burned epidermal tissue from a patient’s own stem cells. That’s the basis of Holoclar, a stem cell-based treatment for severe eye burns approved in Europe in 2015.

Holoclar and similar procedures work well for injured patients with normal epithelia. “We wanted to genetically modify those cells in order to address one of the most important genetic diseases in the dermatology field, which is epidermolysis bullosa (EB), a devastating skin disease,” said De Luca. In EB, patients carry a genetic defect in cell adhesion that causes severe blisters all over their skin and prevents normal healing. A large number of EB patients die as children from the resulting infections, and those who survive seldom get beyond young adulthood before succumbing to squamous cell carcinomas.

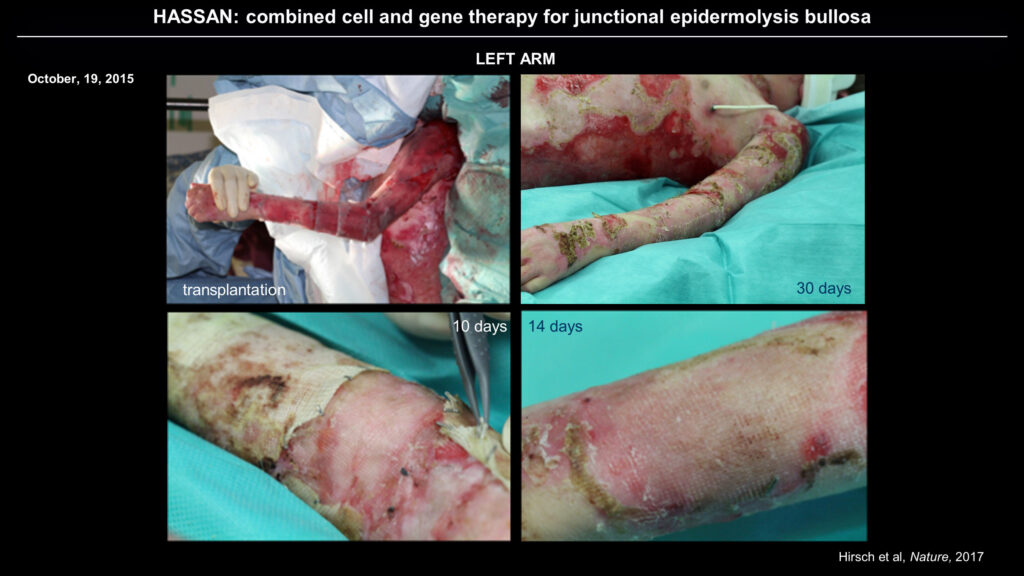

De Luca developed a strategy to isolate stem cells from a skin biopsy, repair the genetic defect in these cells with a retroviral vector, and then grow new skin in culture that can be transplanted back to the patient, replacing their original skin with genetically repaired skin. In 2015, the researchers carried out the procedure on a young boy named Hassan, who had arrived in the burn unit of a German hospital with EB after fleeing Syria. The burn unit was only able to offer palliative care, and his prognosis was poor because of his constant blistering and infections. De Luca’s team received approval to perform their gene therapy on him.

The new strategy, which combines cell and gene therapy, resulted in the restoration of normal skin adhesion in Hassan.

After isolating and modifying epidermal stem cells from Hassan and growing new sheets of skin in culture, De Luca’s team re-skinned the patient’s arms and legs, then his abdomen and back. The complete procedure took about three months. The new skin resists blister formation even when rubbed and heals normally from minor wounds. In the ensuing three and a half years, Hassan has begun growing normally and living an ordinary, healthy life.

Detailed analysis of skin biopsies showed that Hassan’s epidermis has normal cellular adhesion machinery and revealed that his skin is now derived from a population of proliferating transgenic stem cells, with no single clone dominating. By tracing the lineages of cells carrying the introduced transgene, De Luca was able to identify self-renewing transgenic stem cells, intermediate progenitor cells, and fully differentiated stem cells, indicating normal skin growth and replacement.

Besides being good news for the patient, the results confirmed a longstanding theory of skin regeneration. “These data formally prove that the human epidermis is sustained only by a small population of long-lived stem cells that generates [short-lived epithelial] progenitors,” said De Luca, adding that “with this in mind, we’ve started doing other clinical trials.”

The researchers plan to continue targeting junctional as well as dystrophic forms of EB, both of which are genetically distinct from EB simplex. Initial experiments revealed that in these conditions, transplant recipients developed mosaic skin, where some areas continued to be produced from cells lacking the introduced genetic repair. The non-transgenic cells appeared to be out-competing the transgenic cells and supplanting them, undermining the treatment. De Luca and his colleagues developed a modified strategy that gave the transgenic cells a competitive advantage. This approach and additional advances should allow them to achieve complete transgenic skin coverage.

Further Readings

Naik

Bukhari S, Mertz AF, Naik S.

Eavesdropping on the Conversation between Immune Cells and the Skin Epithelium.

International Immunology. 2019;dyx088.

Kobayashi T, Naik S, Nagao K.

Choreographing Immunity in the Skin Epithelial Barrier.

Immunity.2019;50(3):552-565.

Naik S, Larsen SB, Gomez NC, et al.

Inflammatory Memory Sensitizes Skin Epithelial Stem Cells to Tissue Damage.

Nature. 2017;550:475-480.

.

De Luca

De Rosa L, Seconetti AS, De Santis G, et al.

Cell Reports. 2019; 27(7):2036-2049.e6.

Hirsch T, Rothoeft T, Teig N, et al.

Regeneration of the Entire Human Epidermis Using Transgenic Stem Cells.

Nature. 2019;551(7680):327-332.

Latella MC, Cocchiarella F, De Rosa L, et al.

The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2017;137(4):836-44.

.

Good for What Ails Us

Speakers

Masayo Takahashi

RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research

Hiromitsu Nakauchi

Stanford University and University of Tokyo

Highlights

- The first clinical use of iPS cells in humans replaced retinal cells in a patient with age-related macular degeneration.

- “Superdonor” stem cells can evade immune rejection in multiple patients.

- Culturing hematopoietic stem cells has been an ongoing challenge for immunologists.

- Polyvinyl alcohol, used in making school glue, is a superior substitute for bovine serum albumin in stem cell culture media.

- Large doses of hematopoietic stem cells may obviate the need for immunosuppression in stem cell therapy.

An iPS Cell for an Eye

Masayo Takahashi, of RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research, began her talk with a brief description of the new Kobe Eye Center, a purpose-built facility designed to house a complete clinical development pipeline dedicated to curing eye diseases. “Not only cells, not only treatments, but a whole care system is needed to cure the patients,” said Takahashi. In keeping with that philosophy, the Center includes everything from research laboratories to a working eye hospital and a patient welfare facility.

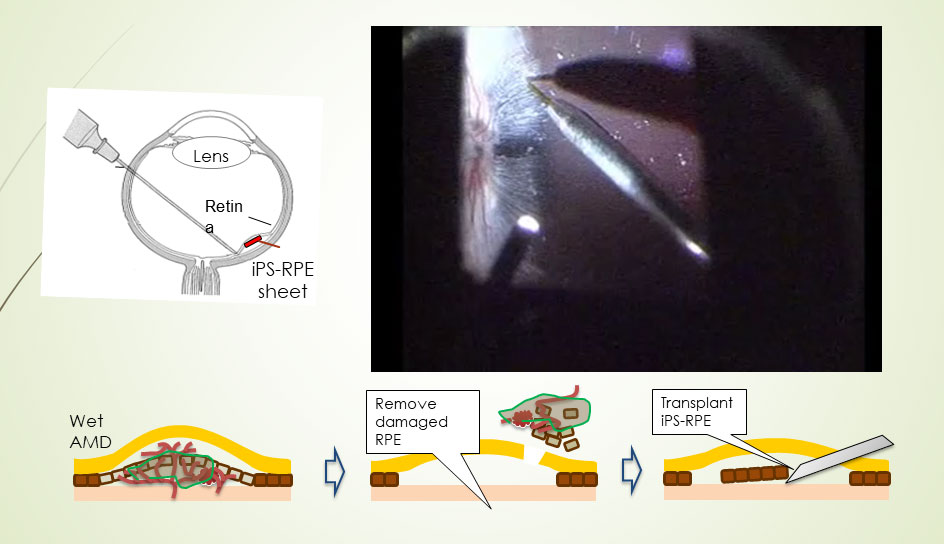

Takahashi’s recent work has focused on treating age-related macular degeneration (AMD). In AMD, the retinal pigment epithelium that nourishes other retinal cells accumulates damage, leading to progressive vision loss. AMD is the most common cause of serious visual impairment in the elderly in the US and EU, and there is no definitive treatment. Fifteen years ago, Takahashi and her colleagues derived retinal pigment epithelial cells from monkey embryonic stem cells and successfully transplanted them into a rat model of AMD, treating the condition in the rodents. They were hesitant to extend the technique to humans, though, because it required suppressing the recipient’s immune response to prevent them from rejecting the monkey cells.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell technology pointed Takahashi toward a new strategy, in which she took cells from a patient, derived iPS cells from them, and then prompted those cells to differentiate into retinal pigment epithelial cells that were perfectly compatible with the patient’s immune system. Her team then transplanted a sheet of these cells into the patient. That experiment, in 2014, was the first clinical use of iPS cells in humans. “The grafted cells were very stable,” said Takahashi, who has checked the graft in multiple ways in the ensuing years.

Having proven that iPS cell-derived retinal grafts can work, Takahashi and her colleagues sought to make the procedure cheaper and faster. Creating customized iPS cells from each patient is a huge undertaking, so instead the team investigated superdonor iPS cells that can be used for multiple patients. These cells, described by Shinya Yamanaka in his keynote address, express fewer types of human leukocyte antigens than most patients, making them immunologically compatible with large swaths of the population. Just four lines of superdonor iPS cells can be used to derive grafts for 40% of all Japanese people.

Transplantation of an iPS cell-derived sheet into the retina ultimately proved successful.

In the next clinical trial, Takahashi’s lab performed several tests to confirm that the patients’ immune cells would not react with the superdonor cells, before proceeding with the first retinal pigment epithelial graft. Nonetheless, after the graft the researchers saw a minuscule fluid pocket in the patient’s retina, apparently due to an immune reaction. Clinicians immediately gave the patient topical steroids in the eye to suppress the reaction. “Then after three weeks or so, the reaction ceased and the fluid was gone, so we could control the immune reaction to the HLA-matched cells,” said Takahashi. Four subsequent patients showed no reaction whatsoever to the iPS superdonor-derived grafts.

While the retinal grafts were successful, none of the patients have shown much improvement in visual acuity so far. Takahashi explained that subjects in the clinical trial all had very severe AMD and extensive loss of their eyes’ photoreceptors. “I think if we select the right patients, we could get good visual acuity if their photoreceptors still remain,” said Takahashi.

Takahashi finished with a brief overview of her other projects, including using aggregates of iPS cells and embryonic stem cells to form organoids, which can self-organize into a retina. She hopes to use this system to develop new therapies for retinitis pigmentosa, another major cause of vision loss. Finally, Takahashi described a project aimed at reducing the cost and increasing the efficacy of stem cell therapies even further by employing a sophisticated laboratory robot. The system, called Mahoro, is capable of learning techniques from the best laboratory technicians, then replicating them perfectly. That should make stem cell culturing procedures much more reproducible and significantly reduce the cost of deploying new therapies.

A Sticky Problem

Hiromitsu Nakauchi, of Stanford University and the University of Tokyo, described his group’s efforts to overcome a decades-old challenge in stem cell research. Scientists have known for over 25 years that all of the blood cells in a human are renewed from a tiny population of multipotent, self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells. In an animal that’s had all of its hematopoietic lineages eliminated by ionizing radiation, a single such cell can reconstitute the entire blood cell population. This protocol is the basis for several experimental models.

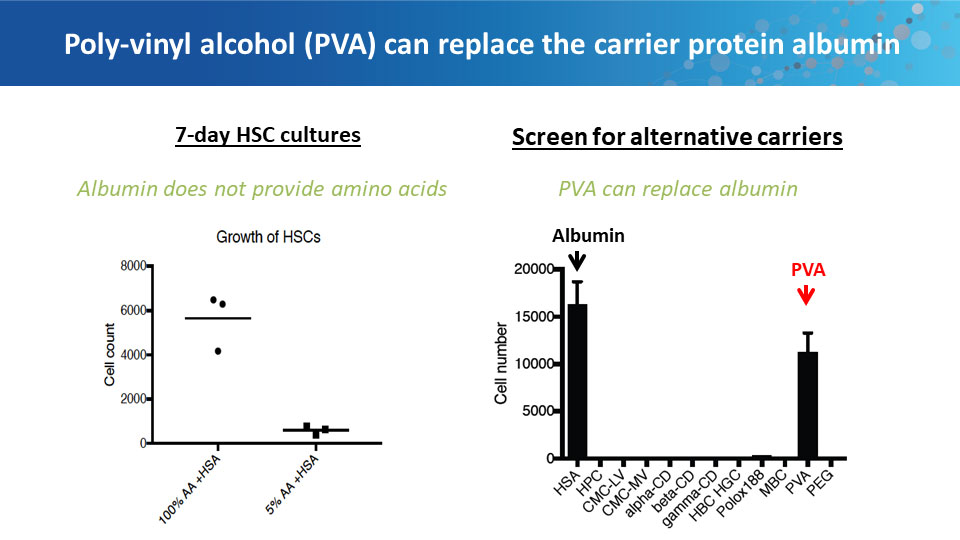

In theory, then, a single hematopoietic stem cell should also be able to multiply indefinitely in pure culture, allowing researchers to produce all types of blood cells on demand. In practice, cultured stem cells inevitably differentiate and die off after just a few generations in culture. Nakauchi and his colleagues have been trying to fix that problem. “After years of hard work, we decided to take the reductionist approach and try to define the components that we use to culture [hematopoietic stem cells],” said Nakauchi.

The team focused on the most undefined component of their culture media: bovine serum albumin (BSA). This substance, a crude extract from cow blood, has been considered an essential component of growth media since researchers first managed to culture mammalian cells. However, Nakauchi’s lab found tremendous variation between different lots of BSA, both in the types and quantities of various impurities in them and in their efficacy in keeping stem cells alive. Worse, factors that appeared to be helpful to the cells in some BSA lots were harmful when present in other lots. “So this is not science; depending on the BSA lot you use, you get totally different results,” said Nakauchi.

Next, the researchers switched to a recombinant serum albumin product made in genetically engineered yeast. That exhibited less variation between lots, and after optimizing their culture conditions they were able to grow and expand hematopoietic stem cells for nearly a month. Part of the protocol they developed was to change the medium every other day, which they found was required to remove inflammatory cytokines and chemokines being produced by the stem cells. That suggested the cells were still under stress, perhaps in response to some of the components of the recombinant serum albumin.

Polyvinyl alcohol can replace BSA in culture medium.

The ongoing problems with serum albumin products led Nakauchi to ask why albumin is even necessary in tissue culture. Scientists have known for decades that cells don’t grow well without it, but why not? While trying to figure out what the albumin was doing for the cells, Nakauchi’s lab tested it against the most inert polymer they could find: polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Best known as the primary ingredient for making school glue, PVA is also used extensively in the food and pharmaceutical industries. To their surprise, hematopoietic stem cells grew better in PVA-spiked medium than in medium with BSA. The PVA-grown cells showed decreased senescence, lower levels of inflammatory cytokines, and better growth rates.

In long-term culture, Nakauchi and his colleagues were able to achieve more than 900-fold expansion of functional mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Transplanting these cells into irradiated mice confirmed that the cells were still fully capable of reconstituting all of the hematopoietic lineages. Further experiments determined that PVA-containing medium also works well for human hematopoietic stem cells.

Besides having immediate uses for basic research, the ability to grow such large numbers of hematopoietic stem cells could overcome a fundamental barrier to using these cells in the clinic. Current hematopoietic stem cell therapies require suppressing or destroying a patient’s existing immune system to allow the transplanted cells to become established, but this immunosuppression can lead to deadly infections. Transplanting a much larger population of stem cells can overcome the need for immunosuppression, but growing enough cells for this approach has been impractical. Using their new culture techniques, Nakauchi’s team can now produce enough hematopoietic stem cells to carry out successful transplants without immunosuppression in mice. They hope to take this approach into the clinic soon.

Further Readings

Takahashi

Jin Z, Gao M, Deng W, et al.

Stemming Retinal Regeneration with Pluripotent Stem Cells.

Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2019;69:38-56.

Maeda, Akiko, Michiko Mandai, and Masayo Takahashi.

Gene and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Therapy for Retinal Diseases.

Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 2019;20.

Matsumoto E, Koide N, Hanzawa H, et al.

PloS One. 2019;14(3):e0212369.

Nakauchi

van Galen P, Mbong N, Kreso A, et al.

Integrated Stress Response Activity Marks Stem Cells in Normal Hematopoiesis and Leukemia.

Cell Reports. 2018; 25(5):1109-1117.e5.

Nishimura T, Nakauchi H.

Generation of Antigen-Specific T Cells from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells.

Methods in Molecular Biology. 2019;1899:25-40.

Yamamoto R, Wilkinson AC, Nakauchi H.

Changing Concepts in Hematopoietic Stem Cells.

Science. 2018;362(6417): 895-896.

A Developing Field

Speakers

Highlights

- A dramatic transition separates early embryonic stem cells from their descendants.

- Newly isolated formative stem cells represent an intermediate step in development.

- Organoids derived from iPS cells provide excellent models for studying human physiology and disease.

In the Beginning

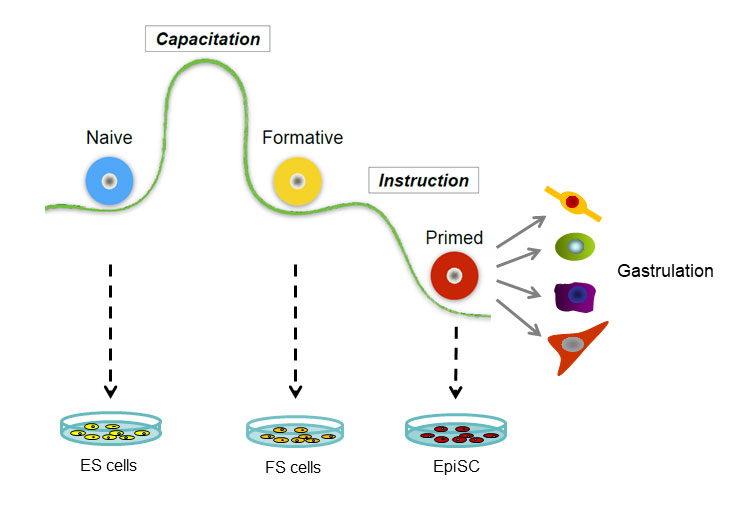

Austin Smith, from the University of Cambridge, gave the final presentation, in which he discussed his studies on the progression of embryonic stem cells through development. In mammals, embryonic development begins with the formation of the blastocyst. In 1981, researchers isolated cells from murine blastocysts and demonstrated that each of them can grow into a complete embryo. Stem cells isolated after the embryo has implanted itself into the uterus, called epiblast stem cells, have lost that ability but gained the potential to differentiate into multiple cell lineages in culture. “So we have two different types of pluripotent stem cells in the mouse, and they’re different in just about every way you could imagine,” said Smith.

Work on other species, including human cells, suggests that this transition between two different types of stem cells is a common feature of mammalian development. The transition from the earlier to the later type of stem cell is called capacitation. To find the factors driving capacitation, Smith and his colleagues looked for differences in gene transcription patterns and chromatin organization during the process, in both human and murine cells. What they found was a global re-wiring of nearly every aspect of the cell’s physiology. “Together these things lead to the acquisition of both germline and somatic lineage competence, and at the same time decommission that extra-embryonic lineage potential,” Smith explained.

Having characterized the cells before and after capacitation, the researchers wanted to isolate cells from intermediate stages of the process to understand how it unfolds. To do that, they extracted cells from mouse embryos right after implantation, then grew them in culture conditions that minimized their exposure to signals that would direct them toward specific lineages. Detailed analyses of these cells, which Smith calls formative stem cells, shows that they have characteristics of both the naive embryonic stem cells and the later epiblast stem cells. Injecting these cells into mouse blastocysts yields chimeric mice carrying descendants of the injected cells in all their tissues. The formative stem cells can therefore function like true embryonic stem cells, albeit less efficiently.

The developmental sequence of pluripotent cells.

Post-implantation human embryos aren’t available for research, but Smith’s team was able to culture naive stem cells and prompt them to develop into formative stem cells. These cells exhibit transcriptional profiles and other characteristics homologous to those seen in the murine formative stem cells.

Having found the intermediate cell type, Smith was now able to assemble a more detailed view of the steps in development. Returning to the mouse model, he compared the chromatin organization of naive embryonic, formative, and epiblast stem cells. The difference between the naive and formative cells’ chromatin was much more dramatic than between the formative and epiblast cells.

Based on the results, Smith proposes that naive embryonic stem cells begin as a “blank slate,” which then undergoes capacitation to become primed to respond to later differentiation signals. The capacitation process entails a dramatic change in the cell’s transcriptional and chromatin organization and occurs around the time of implantation. “We think we now have in culture … a cell that represents this intermediate stage and that has distinctive functional properties and distinctive molecular properties,” said Smith. After capacitation, the formative stem cells undergo a more gradual shift to become primed stem cells, which are the epiblast stem cells in mice.

Smith concedes that the human data are less detailed, but all of the experiments his team was able to do produced results consistent with the mouse model. Other work has also found corroborating results in non-human primate embryos, implying that the same developmental mechanisms are conserved across mammals.

Organoid Recitals

After the presentations, a panel consisting of members of the Innovators in Science Award’s Scientific Advisory Council and Jury took the stage to address a series of questions from the audience.

The panel first took up the question of how researchers can better study human stem cells, given the ethical challenges of working with embryos. Brigid Hogan described organoid cultures, in which researchers stimulate human iPS cells to grow into minuscule organ-like structures. “This is a way of looking at human development at a stage when it’s [otherwise] completely inaccessible,” said Hogan. Other speakers concurred, adding that implanting human organoids into mice provides an especially useful model.

Another audience member asked about the potential for human stem cell therapy in the brain. Hogan pointed to the use of fetal cells for treating Parkinson’s disease as an example, but panelist Hans Schöler suggested that that could be a unique case. Patients with Parkinson’s disease suffer from deficiency in dopamine-secreting neurons, so implanting cells that secrete dopamine in the correct brain region may provide some relief.

Panelists also addressed the use of stem cells in regenerative medicine, where researchers are targeting the nexus of aging, nutrition, and brain health. Emmanuelle Passegué explained that the body’s progressive failure to regenerate itself from its own stem cells is a hallmark of aging. “I think we are getting to an era where transplantation or engraftment [of cells] will not be the answer, it will really be trying to reawaken the normal properties of the [patient’s own] stem cells,” said Passegué.

As the meeting concluded, speakers and attendees seemed to agree that the field of stem cell research, like the cells themselves, is now poised to develop in a wide range of promising directions.