The event provided a collaborative platform among speakers and panelists across academia, industry, government, non-profits, and more to exchange knowledge on ethical responsibilities to improve equity within healthcare and biomedical research.

Published April 22, 2025

By Christina Szalinski

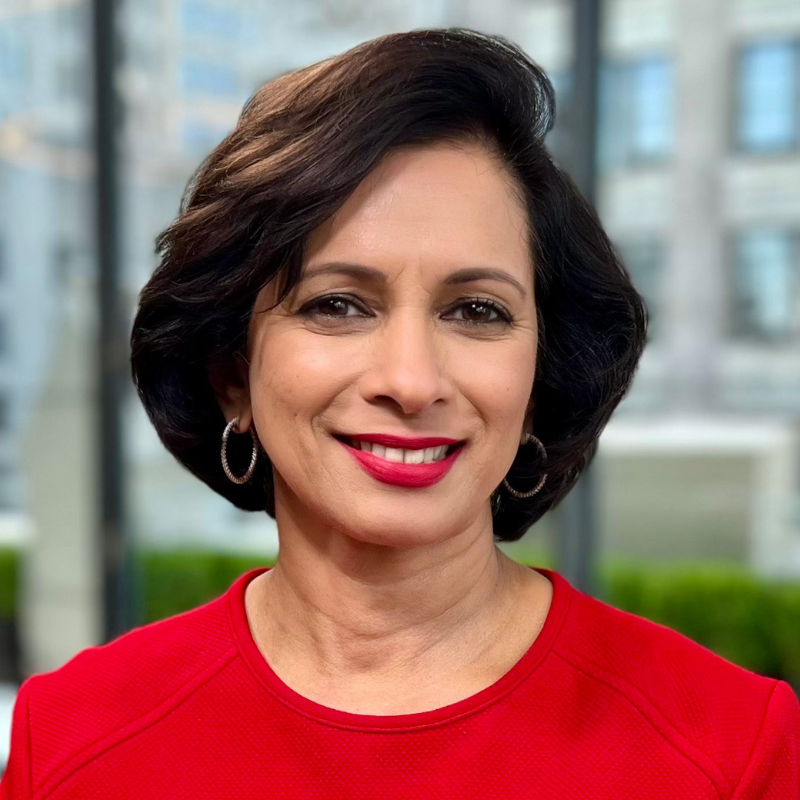

“We are living in a moment that desperately needs clarity of principle and deep moral courage.” And with that statement, Amy Ben Arieh, JD, MPH, executive director of the Fenway Institute, and nationally recognized authority on human research participant protection and inclusive research practices, opened the proceedings of a day-long conference that explored the pursuit of equity and ethical considerations in both healthcare delivery and research conduct.

The New York Academy of Sciences brought together researchers and healthcare professionals for discussions on identifying systemic barriers, sharing best practices and strategies to advance inclusivity, ensuring that healthcare and research benefit all members of society.

Staying the Course: Centering Ethics and Equity in Health Care and Health Research

Opening keynote speaker, Lisa Cooper, MD, MPH, James F. Fries Professor of Medicine and the Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Equity in Health and Health Care at the Johns Hopkins University Schools of Medicine, Nursing, and Public Health, said: “Health equity means that everyone should have a fair opportunity to obtain their full health potential, and that no one should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of socially determined circumstances.” Dr. Cooper is the founder and director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity.

She went on to say that health disparities originate from social norms, institutional economic policies, and environmental living conditions. To address this, two approaches are required: relationship-centered care, which considers the personhood of everyone involved in healthcare, and structural competence, which involves acknowledging and breaking down barriers such as poverty and racism.

Dr. Cooper expressed the need for improvements in healthcare, such as patient-centered communication; community engagement, including a shift from outreach to shared leadership; workforce diversity, which involves establishing a culture of trust through equitable and inclusive treatment and attracting and retaining a diverse group of participants.

In her workplace experience, Dr. Cooper noted that diversity and inclusiveness lead to innovation and creativity as well as overall organizational excellence. Integrating these efforts into the part of the goals leads to success. As far as she is aware, no diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts have led to the marginalization of any group or worsening of health or well-being for any group.

Finally, Dr. Cooper addressed the stumbling blocks to achieving health equity, including the social and political climate, lack of resources, and current uncertainties. She encouraged attendees to transform these challenges into opportunities for growth and innovation. Quoting Dr. Martin Luther King: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” Dr. Cooper closed by noting that we need empathy, self-care, and creativity in order to navigate these obstacles.

Building Trust through Representation: Community Engagement and Research Practices

A panel, moderated by Carol R. Horowitz, MD, professor of population health science and policy at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, brought together Carl Streed, MD, associate professor of medicine and research lead for the GenderCare Center at Boston University; Consuela Wilkins, MD, senior associate dean for equity at Vanderbilt University; Randi Woods, executive director of Sisters Together Reaching; and Anhtuh Huang, PhD, deputy director of We Act for Environmental Justice in Harlem.

The central theme of the panel was engaging the local community beyond transactional interactions. The panelists discussed how some institutions have historically perpetuated harm against marginalized communities, which explains why communities have a justified skepticism of institutions and research. However, as Dr. Wilkins pointed out, when we talk about trust and building trust, it can put the burden on the community—the people who have been disenfranchised and harmed. Instead, she recommends focusing on demonstrating trustworthiness.

To build trust, Randi Woods recommended collaborating with the community and including community perspectives in research priorities and design, as well as moving closer to shared leadership.

One way to establish relationships within the local community, Dr. Streed said, is through Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), which can require researchers to consider how the community informs the research or how the research benefits the community.

Dr. Huang noted the importance of community engagement, that considered other viewpoints, shared resources, and strategized partnerships, as well as a communications plan to navigate conflicts and challenges.

Building a Health Research Workforce that Centers Equity and Community

Brian Smedley, PhD, senior fellow in the health policy division at the Urban Institute, said that the current healthcare systems are designed to generate profit rather than health, which create structural inequities. He recommended increasing transparency throughout the research process and training professionals in community engaged practices. He stressed the importance of involving community members in every stage of research—from setting priorities and developing research questions to interpreting and disseminating results to rebuild trust in medical and public health institutions.

Ethical and Equitable Strategies for Diversifying the Biomedical Research Workforce

Emma Benn, DrPH, associate professor in the Center for Biostatistics and Department of Population Health Science and Policy at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, moderated a panel that included Philip Alberti, PhD, founding director of the Association of American Medical Colleges; Hila Berger, MPH, assistant vice president of research regulatory affairs at Rutgers Research; and Linda Pololi, MBBS, distinguished research scientist at the Institute for Economic and Racial Equity at Brandeis University and Director of the National Initiative on Gender, Culture and Leadership in Medicine at Brandeis. The overarching message was that diversifying the biomedical research workforce is critical for improving scientific innovation and healthcare outcomes.

Dr. Pololi noted that research shows that while many faculty believe in the importance of diversity, only a third think that race and ethnicity should be considered in hiring and promoting diverse candidates. Yet it was pointed out by Dr. Benn, that diverse teams lead to higher productivity and accelerated innovation.

The panelists stressed that diversifying the workforce isn’t just about representation, but about fundamentally changing institutional cultures. They shared examples of progress, such as creating community advisory boards for research protocols and bringing up diversity and inclusion in the hiring process. Additionally, they recommended measuring the value of outcomes that diverse research teams provide, encouraging accrediting bodies to influence institutional change, and creating systems to elevate diverse voices. Dr. Alberti and Hila Burger also suggested that K-12 education is an important place to create equal opportunity in the STEM pipeline by encouraging all young people to see themselves as having a place in STEM.

Is AI a Threat or a Solution for Equity, Engagement, and Inclusion?

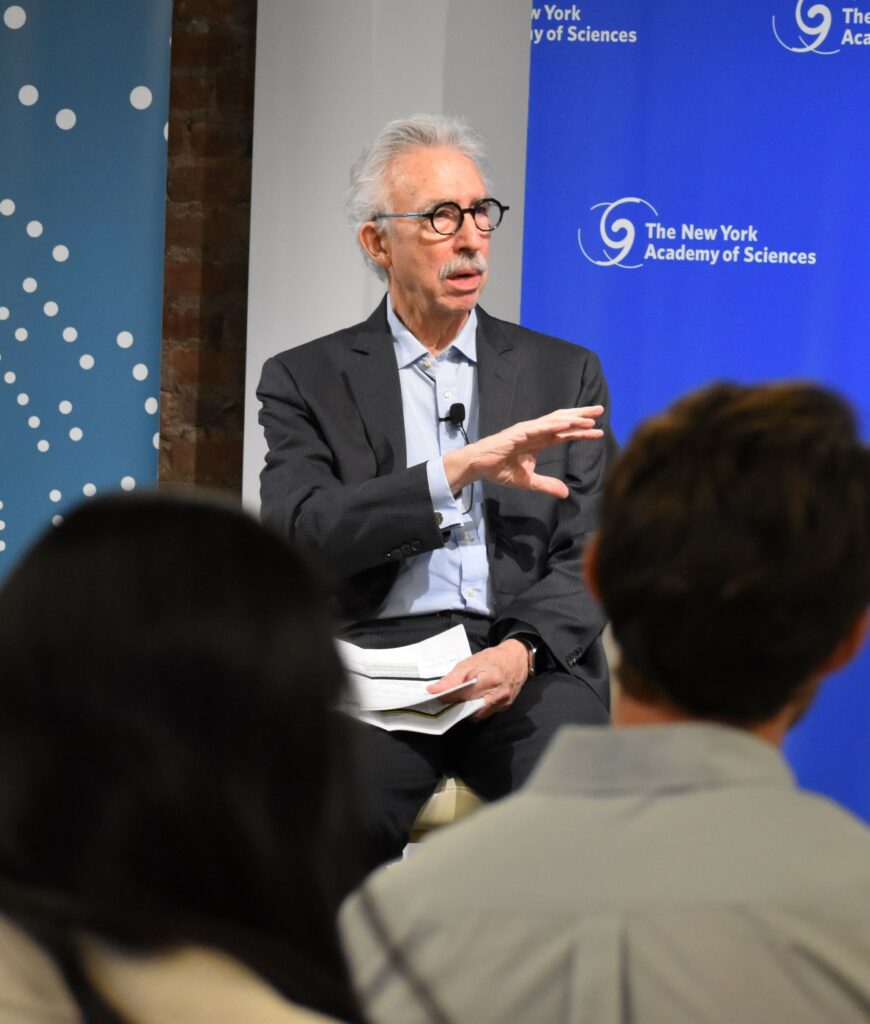

Bernard Lo, MD, emeritus professor of medicine and director emeritus of the Program in Medical Ethics at University of California, San Francisco presented on the complex relationship between artificial intelligence and equity, highlighting AI’s potential to be both a threat and potential solution for improving diversity and inclusion.

He explained that AI systems can perpetuate existing biases when they are trained on historically skewed datasets. AI can discriminate in areas like hiring, the legal system, loan procurement, and healthcare by replicating biases embedded in training data.

However, he also outlined several ways generative AI could make positive changes by detecting bias in text, analyzing large data sets from healthcare records, improving patient communication, simplifying the process by which people access services for housing or financial insecurity, and developing easier-to-understand consent protocols in research. Dr. Lo noted that AI could also make certain healthcare screens cheaper and more accessible, like eye scans for diabetic retinopathy. Rather than allowing AI to perpetuate inequalities, he said that we need a collaborative, community-engaged approach for it to become a tool for empowerment.

Ensuring Equity and Ethical Practices in Clinical Trials

Giselle Corbie, MD, professor of social medicine at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, moderated a panel exploring inclusive research practices, and emphasized the critical importance of trust and community engagement. Ebony Boulware, MD, dean of Wake Forest School of Medicine and health equity researcher; and Maggie Alegria, PhD, chief of the Disparities Research Unit at Mass General Hospital participated.

A fundamental problem, Dr. Corbie noted, is that previous poor treatment of minorities and women by institutions, may be why they are reluctant to participate in research. A solution is to engage marginalized communities and populations in the research design.

Drs. Boulware and Corbie suggested using recruitment tools that ensure that there is no discrimination in the selection of participants, such as AI screening of health records, which can increase diversity in clinical trials. Also, by ensuring racial, ethnic and linguistic concordance in research studies, Dr. Alegria said, it can make participants feel safe and heard.

The panelists stressed the importance of returning research results to communities, providing fair compensation, and making sure that interventions don’t end when a study is over. They also emphasized the need for institutional accountability and sensitivity on the part of researchers when it comes to previous historical inequities. They also highlighted the critical need for meeting with policymakers to help keep successful interventions going by involving communities and community-based organizations, as well as a commitment to creating research practices that are inclusive to diverse populations.

Looking to the Future: Ensuring a Healthier America for All

David Williams, PhD, professor of public health and professor of African and African-American studies at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, gave the closing keynote, highlighting that all Americans should have better health. The U.S. spends the most on medical care globally, but has an average lower life expectancy than more than 60 industrialized countries.

Dr. Williams noted that a recent study showed that because of racial disparities in health, 203 Black people die prematurely every day. This isn’t just a loss of life, he said, it is also $15.8 trillion in loss every year. And because of racial inequities in health, Black children are three times more likely to lose a mother by age 10, and Black adults are ten times more likely to lose a child by age 30.

Programs that create equity help everyone, he said, citing the example of the State of Delaware, which implemented colorectal cancer screening and treatment regardless of health insurance while combining it with outreach. The program eliminated racial inequities in screening and nearly eliminated the mortality difference for African-Americans. The initiative provided care to all, and a net savings of $1.5 million per year due to reduced incidence and earlier diagnosis.

Dr. Williams said that we need to reduce implicit bias in care. He explained that short anti-bias interventions don’t always reduce bias, according to the evidence. Dr. Patricia Divine, professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, developed a 12-week program that teaches providers multiple strategies and reduces bias. Initial research shows that it works.

Dr. Williams also emphasized the importance of diversifying the healthcare workforce. A study from Northern California gave African-American males a coupon to go to a nearby hospital for screening. Once at the hospital, they were randomly assigned to a doctor of their own race or another doctor. Men who saw a doctor of their own race were more likely to talk about other health problems, get screened for diabetes, receive the flu vaccine, and be screened for cholesterol. Additionally, studies show that when there are more Black primary care providers in a county, the higher the life expectancy for Black people in that area.

“Most Americans are unaware studies show that racial inequities in health even exist. We need to pay attention to how we talk and frame the policy solutions,” Dr. Williams said. “We cannot be silent…we need to redouble efforts to work together to build a healthier America for all.”

The New York Academy of Sciences hosts a diverse array of events year-round. Check out our upcoming events.