Researchers across the globe are doing their part to both fuel and sustain a healthy planet.

Published May 1, 2018

By Hallie Kapner

To the untrained eye, the black dots speckling the corn leaves in the greenhouses at Iowa State University’s Plant Sciences Institute could be anything — blight, mold, rot. But to Patrick Schnable, the Institute’s director and the C.F. Curtiss Distinguished Professor and Iowa Corn Endowed Chair in Genetics at ISU, the dots are the future of precision irrigation — a simple and inexpensive window into how plants use a precious global resource: water.

Dubbed the “plant tattoo,” the dots are bits of graphene oxide deposited on a gas-permeable tape to form an easily applied sensor that precisely measures transpiration — water loss — on an individual-leaf basis. As leaves lose water, the moisture changes graphene’s electrical conductivity. By measuring those changes, Schnable and his collaborators can observe transpiration in real time.

“If you have a plant under drought stress and you water it or it rains, you can track water moving up through the plant,” Schnable said. “For the first time ever, we can observe plants reacting to an irrigation event as it happens.”

The plant tattoo is one of countless research initiatives underway worldwide that aim to conserve and maximize natural resources, improve access to nutrition, prevent and treat disease, and boost the health and well-being of the planet’s people and wildlife.

Schnable and his collaborator, Liang Dong, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at ISU, envision a day when farmers can use plant sensors to guide irrigation decisions and breeders can use them to create drought-resistant varietals. The researchers are already adapting the technology for use beyond the Iowa cornfields. While the current version requires connection to a control box to provide both voltage and transpiration rate analysis, plant tattoo 2.0 will be wireless and smartphone-compatible. Such refinements will drop the cost of the system even further, making the sensors accessible for areas of the developing world where every drop of water counts.

Cultivating “Black Rice”

Maximizing efficiencies in breeding and irrigation of agricultural crops is one key part of meeting the global goals related to hunger, nutrition and stewardship of the land. Equally critical are efforts to identify and promote staple crops that pack maximum nutrition, explained Ujjawal Kr. S. Kushwaha, PhD Scholar in Genetics and Plant Breeding at G.B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology in Pantnagar, India.

More than half of the world’s population relies on rice for at least 20 percent of their daily calories. If Kushwaha had his way, the typical white rice of subsistence would be replaced by black rice, an heirloom variety sometimes called “forbidden” rice, and one of nature’s nutritional powerhouses.

“No other rice has higher nutritional content,” Kushwaha said. “It’s high in fiber, anthocyanins and other antioxidants, vitamins B and E, iron, thiamine, magnesium, niacin and phosphorous. Consumed at scale, it could have a significant impact on malnutrition.”

Decades of effort to boost the nutritional content of rice have yielded biofortified varietals rich in iron, zinc and provitamin A. While addressing these highly prevalent micronutrient deficiencies is critical, Kushwaha contends that black rice could address both a broad spectrum of nutritional deficiencies as well as provide anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic benefits.

However, black rice is not widely cultivated outside of China, and most varietals are relatively low-yield, which drives the crop’s high cost. Kushwaha is working to shift that equation, spreading the black rice gospel with the hope of boosting demand and incentives for farmers to develop higher-yield varietals, which could make a crop once reserved for royalty as affordable as white rice.

Anticipating the potential hurdles of acceptance — factors such as taste and color often determine whether new varietals are adopted or rejected — Kushwaha and others cultivating nutrient-rich rices have determined that black rice could be bred to minimize color while preserving much of its nutritional value. “Some of the qualities could be reduced, but it’s still far better than white rice,” he noted.

Plant Power

Plants already do far more than just feed the world — we derive fuel, fabrics, medicinal compounds and much more from them. Yet over the past two decades, a new role for plants has emerged — one that may revolutionize one of the most important pipelines for global health: vaccine production.

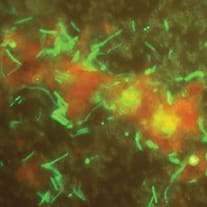

Conventional vaccine manufacturing relies on primary cells — like chicken eggs — mammalian cell lines, yeast cells or bacteria. These approaches have well-known limitations, such as long production times, variable yields and risk of contamination by other human pathogens. As Kathleen Hefferon, a virologist and Fulbright Canada Research Chair of Global Food Security at the University of Guelph explained, plants are not merely viable alternative bioreactors for many types of vaccines — they are production superstars.

First-generation plant-made biopharmaceuticals were derived from transgenic crops, but public concerns about GMOs, as well as variability in the amount of vaccine protein produced per plant, drove the development of a second — and now dominant — production method. Plant virus expression vectors are used to deliver genes for producing vaccine proteins into the leaves of plants such as tobacco and potato, turning common crops into factories capable of churning out huge quantities of vaccine protein faster and more cheaply than any other method.

Plant-made vaccine proteins carry no risk of contamination with mammalian pathogens, and better still, plants can produce similar post-translational modifications to human cells, which increases biocompatibility. Hefferon believes plant-made biopharmaceuticals will grow exponentially over the next five years, due in part to increased interest in stockpiling vaccines against pandemic flu and other diseases.

“It’s hard to stockpile vaccines produced in mammalian systems, and it’s very hard to produce enough vaccine in time to be helpful in an outbreak,” she said. “Plants offer a clear advantage here.”

Several pharmaceutical companies have plant-made vaccines and therapeutics in clinical trials, but the public is already familiar with one experimental drug that made headlines in 2015 — ZMapp, which was used to treat several Ebola-infected healthcare workers in West Africa. Hefferon is also quick to emphasize that the lower-cost profile of plant-made vaccines has special relevance for cancer prevention in the developing world, where rates of cancers linked to vaccine-preventable viruses, including HPV, are skyrocketing.

“We’re already in the running to advance the science toward pharmaceutical production in plants,” she said. “The current systems have so many limitations and plants are an incredible alternative.”

On Land and Sea

Just as human health is inextricably tied to the health of the air, soil, water and environment, so too is the health of the animals we rely on for work and food. In the tropical regions of Mexico, scientists including veterinarians Felipe Torres-Acosta and Carlos Sandoval-Castro, and organic chemist Gabriela Mancilla, of Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan (UADY), are studying how sheep and goats regulate their own health through diet.

The team at UADY has been devising strategies to improve the health of ruminants in tropical environments for 30 years. One of their standout findings is that malnourished animals are less resilient to native parasites, and while farmers can boost resilience with supplemental food, access to native flora is critical for keeping the host-parasite relationship in balance.

The UADY team showed that sheep and goats left to forage on their own in the Mexican jungle feast on an astonishing 60 different plant species per day, adjusting their food choices based on seasonal availability. Diving deeper into the connection between diet and immune resistance, Torres-Acosta’s team collected samples of ruminants’ preferred foods, analyzing them for nutritional content and the presence of anthelmintic activity.

Photo: Hudson Rivers Fisheries Unit Staff

Analysis reveals that most local flora do contain anti-parasitic compounds, and Mancilla is working to discover the mechanisms by which they act to control parasite load. The team is investigating whether animals intentionally seek a diet rich in plants that naturally limit parasite infection. This work, as well as similar research in sheep and goats around the world, is already impacting how some small farmers treat infections.

“If animals have access to their native foods, they can keep parasites in check, which reduces the need for medication and allows farmers to treat only the sickest animals,” Torres-Acosta said. “The most interesting things we’re learning come directly from observing the animals — given the choice, animals know what they need to eat to stay healthy, and we can learn so much from their innate wisdom.”

Off the shores of Long Island, New York, Stephen Frattini, founder of the Center for Aquatic Animal Research and Management (CFAARM), is trying to bring a similar sensibility to the seafood industry, which supplies three billion people worldwide with their primary source of protein. Frattini, a veterinarian, focuses not just on how fisheries and aquaculture operations could improve fish welfare, though his passion for that subject runs deep.

His goals are bigger, and include uniting experts in animal welfare, engineering, health management, feed development and consumer psychology to transform the seafood industry from a profoundly siloed one, rife with inefficiencies and transparency issues, to an integrated one that places the health of the environment, people and fish front and center. Frattini believes that a more integrated seafood industry could revitalize coastal communities both in the United States and developing countries, as well as advance production strategies already known to improve fish health, such as emphasizing diversity over monoculture.

“We still need a much better understanding of fish behavior in captivity and what we can do to create happier, healthier animals, but I’m convinced we can increase efficiencies while increasing fish contentment, which is a win for animals, the environment and the industry,” he said.

A Matter of Will

Decades of fast-paced discovery in medical research, coupled with high-tech advances in equipment, procedures and information technologies have yielded many of the solutions necessary to provide high-quality healthcare to all. No cohort in history has been better equipped than ours to identify problems, connect patients with preventative and acute care and measure and understand the outcomes. Yet nations around the globe, from the most developed to the least, struggle to manage the cost, logistics and delivery of basic human health services.

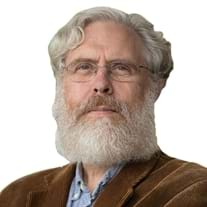

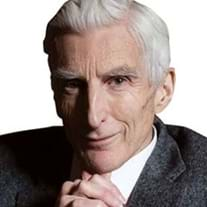

A desire to identify best practices and help spread their adoption drove William Haseltine, a biologist and former professor at Harvard Medical School, known for his pioneering research on HIV/AIDS and the human genome, to found the nonprofit ACCESS Health International 10 years ago.

ACCESS Health has since partnered with nations in every region of the world to better understand the systems that improve primary care, lower maternal and child mortality, and meet the needs of an aging population while maintaining affordability. From a revolutionary emergency-response system in India that serves 700 million people each year with greater efficiency and lower cost than any system in the West, to hospitals using information technology to implement radical transparency and accountability systems that are improving patient safety, Haseltine and the ACCESS Health team have found no shortage of strategies that save and improve lives within budget. Bringing them to bear on the global problem of healthcare access is mainly a matter of will.

“We have a lot of knowledge that can be deployed broadly across the globe, but there has to be a desire and incentive to change,” Haseltine said.

The 17 SDGs can be viewed as a tally of ways people and planet can suffer and struggle. But they can also be viewed as vision of hope, a commitment by 193 nations to alleviate pain and work toward a healthier, more equal future.

“We have come to the point where we have the ability to dramatically improve health outcomes, whether it’s in environmental health, or improving maternal and infant mortality,” said Haseltine. “It all comes down to the question: do we have the will to do it? When the answer is yes, it’s transformative.“

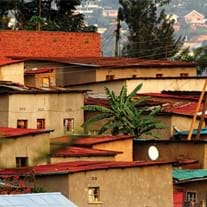

Drone Delivery Takes Off In Rwanda

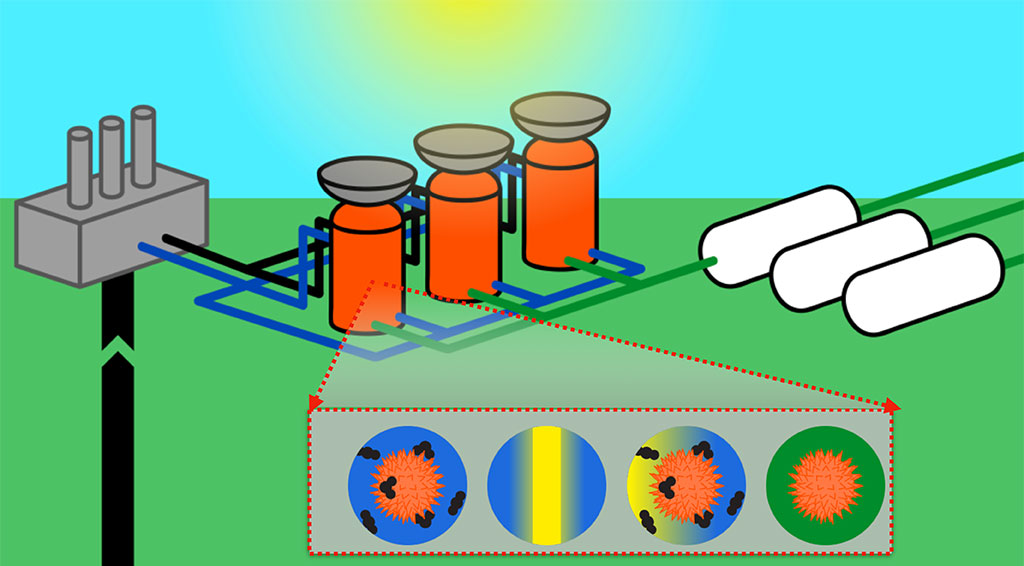

Delivering goods via drones is not a new idea, but it’s providing an important sustainable lifeline to rural communities in Rwanda that are benefiting from the technology.

California-based automated logistics company, Zipline and the Government of Rwanda have collaborated on the world’s first national drone delivery service for on-demand emergency blood deliveries to transfusion clinics across the country. Since its launch in October, 2016, Zipline has flown more than 7,500 flights covering 300,000 km, and delivered 7,000 units of blood to physicians and medical workers in Rwandan villagers nationwide.

Zipline’s technology was developed for longer-haul flights than typical drones and have a round trip range of 160 kilometers. The drones can carry 1.5 kilos of cargo and cruise at 110 kilometers an hour.

More importantly the craft are built to handle the challenges of Rwanda’s mountainous terrain and extreme weather conditions. They look more like fixed wing airplanes than the typical quadcopter image, but it is one of the reasons why they are capable of flying faster and farther than standard craft; imperative for speeding-up the delivery of life-saving medical supplies to remote communities.

The airplanes are powered by lithium-ion battery packs. Two twin electric motors provide reliability at a low operating cost. Redundant motors, batteries, GPS and other electronics provide the safety features, in addition to a parachute-enabled landing system. The planes fly on predetermined routes and are monitored by a Zipline operator.

Also see: Innovation Challenge in Rwanda on “Green Schools, Green Homes, Green Communities”