Overview

The New York Academy of Sciences and the Blavatnik Family Foundation hosted the annual Blavatnik Science Symposium on July 15–16, 2019, uniting 75 Finalists, Laureates, and Winners of the Blavatnik Awards for Young Scientists. Honorees from the UK and Israel Awards programs joined Blavatnik National and Regional Awards honorees from the U.S. for what one speaker described as “two days of the impossible.” Nearly 30 presenters delivered research updates over the course of nine themed sessions, offering a fast-paced peek into the latest developments in materials science, quantum optics, sustainable technologies, neuroscience, chemical biology, and biomedicine.

Symposium Highlights

- Computer vision and machine learning have enabled novel analyses of satellite and drone images of wildlife, food crops, and the Earth itself.

- Next-generation atomic clocks can be used to study interactions between particles in complex many-body systems.

- Bacterial communities colonizing the intestinal tract produce bioactive molecules that interact with the human genome and may influence disease susceptibility.

- New catalysts can reduce carbon emissions associated with industrial chemical production.

- Retinal neurons display a surprising degree of plasticity, changing their coding in response to repetitive stimuli.

- New approaches for applying machine learning to complex datasets is improving predictive algorithms in fields ranging from consumer marketing to healthcare.

- Breakthroughs in materials science have resulted in materials with remarkable strength and responsiveness.

- Single-cell genomic studies are revealing some of the mechanisms that drive cancer development, metastasis, and resistance to treatment.

Speakers

Emily Balskus, PhD

Harvard University

Chiara Daraio, PhD

Caltech

William Dichtel, PhD Northwestern University

Elza Erkip, PhD

New York University

Lucia Gualtieri, PhD

Stanford University

Ive Hermans, PhD

University of Wisconsin – Madison

Liangbing Hu, PhD

University of Maryland, College Park

Jure Leskovec, PhD

Stanford University

Heather J. Lynch, PhD

Stony Brook University

Wei Min, PhD

Columbia University

Seth Murray, PhD

Texas A & M University

Nicholas Navin, PhD, MD

MD Anderson Cancer Center

Ana Maria Rey, PhD

University of Colorado Boulder

Michal Rivlin, PhD

Weizmann Institute of Science

Nieng Yan, PhD

Princeton University

Event Sponsor

Technology for Sustainability

Speakers

Heather J. Lynch

Stony Brook University

Lucia Gualtieri

Stanford University

Seth Murray

Texas A & M University

Highlights

- Machine learning algorithms trained to analyze satellite imagery have led to the discovery of previously unknown colonies of Antarctic penguins.

- Seismographic data can be used to analyze more than just earthquakes—typhoons, hurricanes, iceberg-calving events and landslides are reflected in the seismic record.

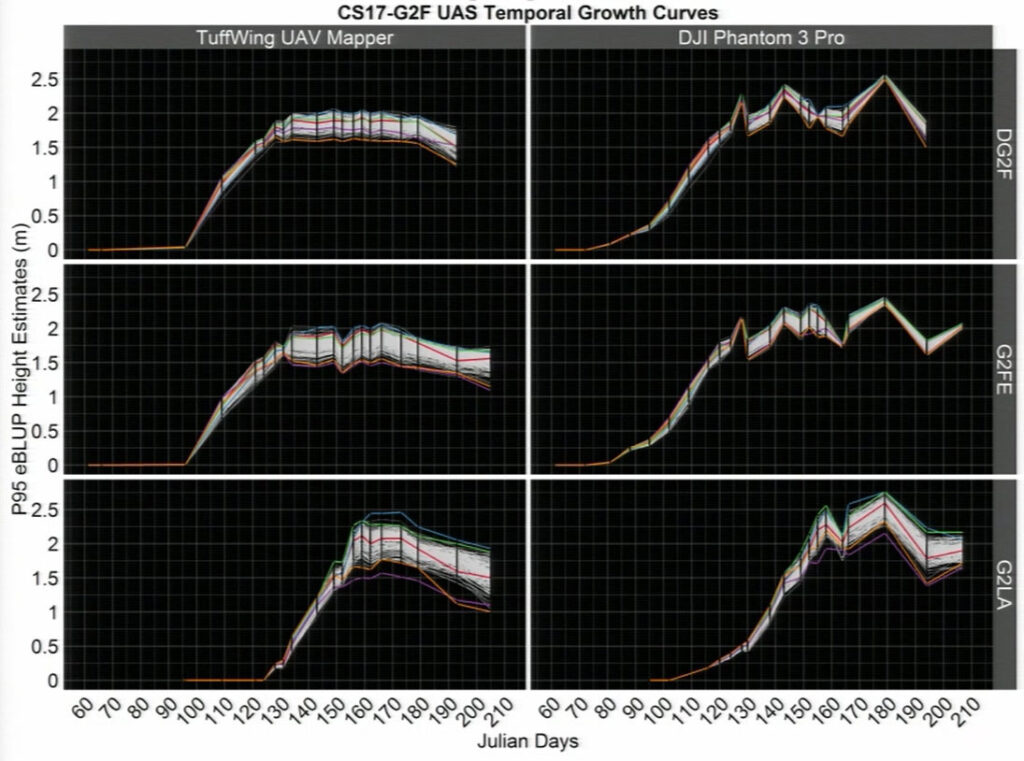

- Unmanned aerial systems are a valuable tool for phenotypic analysis in plant breeding, allowing researchers to take frequent measurements of key metrics during the growing season and identify spectral signatures of crop yield.

Satellites, Drones, and New Insights into Penguin Biogeography

Satellite images have been used for decades to document geological changes and environmental disasters, but ecologist and 2019 Blavatnik National Awards Laureate in Life Sciences, Heather Lynch, is one of the few to probe the database in search of penguin guano. She opened the symposium with the story of how the Landsat satellite program enabled a surprise discovery of several of Earth’s largest colonies of Adélie penguins, a finding that has ushered in a new era of insight into these iconic Antarctic animals.

Steady streams of high quality spatial and temporal data regularly support environmental science. In contrast, Lynch noted that wildlife biology has advanced so slowly that many field techniques “would be familiar to Darwin.” Collecting information on animal populations, including changes in population size or migration patterns, relies on arduous and imprecise counting methods. The quest for alternative ways to track wildlife populations—in this case, Antarctic penguin colonies—led Lynch to develop a machine learning algorithm for automated identification of penguin guano in high resolution commercial satellite imagery, which can be combined with lower resolution imagery like that coming from NASA’s Landsat program. Pairing measurements of vast, visible tracts of penguin guano—the excrement colored bright pink due to the birds’ diet—with information about penguin colony density yields near-precise population information. The technique has been used to survey populations in known penguin colonies and enabled the unexpected discovery of a “major biological hotspot” in the Danger Islands, on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. This Antarctic Archipelago is so small that it is doesn’t appear on most maps of the Antarctic continent, yet it hosts one of the world’s largest Adélie penguin hotspots.

Lynch and her colleagues are developing new algorithms that utilize high-resolution drone and satellite imagery to create centimeter-scale, 3D models of penguin terrain. These models feed into detailed habitat suitability and population-tracking analyses that further basic research and can even influence environmental policy decisions. Lynch noted that the discovery of the Danger Island colony led to the institution of crucial environmental protections for this region that may have otherwise been overlooked. “Better technology actually can lead to better conservation,” she said.

Listening to the Environment with Seismic Waves

The study of earthquakes has dominated seismology for decades, but new analyses of seismic wave activity are broadening the field. “The Earth is never at rest,” said Lucia Gualtieri, 2018 Blavatnik Regional Awards Finalist, while reviewing a series of non-earthquake seismograms that show constant, low-level vibrations within the Earth. Long discarded as “seismic noise,” these data, which comprise more than 90% of seismograms, are now considered a powerful tool for uniting seismology, atmospheric science, and oceanography to produce a holistic picture of the interactions between the solid Earth and other systems.

Nearly every environmental process generates seismic waves. Hurricanes, typhoons, and landslides have distinct vibrational patterns, as do changes in river flow during monsoons and “glacial earthquakes” caused by ice calving events. Gualtieri illustrated how events on the surface of the Earth are reflected within the seismic record—even at remarkably long distances—including a massive landslide in Alaska detected by a seismic sensor in Massachusetts. Gualtieri and her collaborators are tapping this exquisite sensitivity to create a new generation of tools capable of measuring the precise path and strength of hurricanes and tropical cyclones, and for making predictive models of cyclone strength and behavior based on decades of seismic data.

Improving Crop Yield Using Unmanned Aerial Systems and Field Phenomics

Plant breeders like Seth Murray, 2019 Blavatnik National Awards Finalist, are uniquely attuned to the demands a soaring global population places on the planet’s food supply. Staple crop yields have skyrocketed thanks to a century of advances in breeding and improved management practices, but the pressure is on to create new strategies for boosting yield while reducing agricultural inputs. “We need to grow more plants, measure them better, use more genetic diversity, and create more seasons per year,” Murray said. It’s a tall order, but one that he and a transdisciplinary group of collaborators are tackling with the help of a fleet of unmanned aerial systems (UAS), or drones.

Genomics has transformed many aspects of plant breeding, but phenotypic, rather than genotypic, information is more useful for predicting crop yield. Using drones equipped with specialized equipment, Murray has not only automated many of the time-consuming measurements critical for plant phenotyping, such as tracking height, but has also identified novel metrics that can accelerate the development of new varietals. Spectral signatures obtained via drone can be used to identify top-yielding varietals of maize even before the plants are fully mature. Phenotypic features distilled from drone images are also being used to determine attributes such as disease resistance, which directly influence crop management. Murray’s team is modeling the influence of thousands of phenotypes on overall crop performance, paving the way for true phenomic selection in plant breeding.

Further Readings

Lynch

Borowicz A, McDowall P, Youngflesh C, et al.

Multi-modal survey of Adélie penguin mega-colonies reveals the Danger Islands as a seabird hotspot.

Sci Rep. 2018 Mar 2;8(1):3926.

Che-Castaldo C, Jenouvrier S, Youngflesh C, et al.

Nat Commun. 2017 Oct 10;8(1):832.

McDowall P, Lynch HJ.

Ultra-Fine Scale Spatially-Integrated Mapping of Habitat and Occupancy Using Structure-From-Motion.

PLoS One. 2017 Jan 11;12(1):e0166773.

Murray

Zhang M, Cui Y, Liu YH, et al.

Accurate prediction of maize grain yield using its contributing genes for gene-based breeding.

Genomics. 2019 Feb 28. pii: S0888-7543(18)30708-0.

Shi Y, Thomasson JA, Murray SC, et al.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for High-Throughput Phenotyping and Agronomic Research.

PLoS One. 2016 Jul 29;11(7):e0159781.

Quantum Optics

Speakers

Highlights

Atomic Clocks: From Timekeepers to Quantum Computers

Further Readings

Chemical Biology

Speakers

Emily Balskus

Harvard University

Highlights

- The human gut is colonized by trillions of bacteria that are critical for host health, yet may also be implicated in the development of diseases including colorectal cancer.

- For over a decade, chemists have sought to resolve the structure of a genotoxin called colibactin, which is produced by a strain of E. coli commonly found in the gut microbiome of colorectal cancer patients.

- By studying the specific type of DNA damage caused by colibactin, researchers found a trail of clues that led to a promising candidate structure of the colibactin molecule.

Gut Reactions: Understanding the Chemistry of the Human Gut Microbiome

The composition of the trillions-strong microbial communities that colonize the mammalian intestinal tract is well characterized, but a deeper understanding of their chemistry remains elusive. Emily Balskus, the 2019 Blavatnik National Awards Laureate in Chemistry, described her lab’s hunt for clues to solve one chemical mystery of the gut microbiome—a mission that could have implications for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening and early detection.

Some commensal E. coli strains in the human gut produce a genotoxin called colibactin. When cultured with human cells, these strains cause cell cycle arrest and DNA damage, and studies have shown increased populations of colibactin-producing E. coli in CRC patients. Previous studies have localized production of colibactin within the E. coli genome and hypothesized that the toxin is synthesized through an enzymatic assembly line. Yet every attempt to isolate colibactin and determine its chemical structure had failed.

Balskus’ group took “a very different approach,” in their efforts to discover colibactin’s structure. By studying the enzymes that make the toxin, the team uncovered a critical clue: a cyclopropane ring in the structure of a series of molecules they believed could be colibactin precursors. This functional group, when present in other molecules, is known to damage DNA, and its detection in the molecular products of the colibactin assembly line led the researchers to consider it as a potential mechanism of colibactin’s genotoxicity.

In collaboration with researchers at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Balskus’ team cultured human cells with colibactin-producing E. coli strains as well as strains that cannot produce the toxin. They identified and characterized the products of colibactin-mediated DNA damage. “Starting from the chemical structure of these DNA adducts, we can work backwards and think about potential routes for their production,” Balskus explained.

Further studies revealed that colibactin triggers a specific type of DNA damage that requires two reactive groups—likely represented by two cyclopropane rings in the final toxin structure—a pivotal discovery in deriving what Balskus believes is a strong candidate for the true colibactin structure. Balskus emphasized that this work could illuminate the role of colibactin in carcinogenesis, and may lead to cancer screening methods that rely on detecting DNA damage before cells become malignant. The findings also have implications for understanding microbiome-host interactions. “These studies reveal that human gut microbiota can interact with our genomes, compromising their integrity,” she said.

Further Readings

Balskus

Jiang Y, Stornetta A, Villalta PW et al.

Reactivity of an Unusual Amidase May Explain Colibactin’s DNA Cross-Linking Activity.

J Am Chem Soc. 2019 Jul 24;141(29):11489-11496.

Wilson MR, Jiang Y, Villalta PW, et al.

The human gut bacterial genotoxin colibactin alkylates DNA.

Science. 2019 Feb 15;363(6428).

Synthetic Methodology

Speakers

Ive Hermans

University of Wisconsin – Madison

William Dichtel

Northwestern University

Highlights

- The chemical industry is a major producer of carbon dioxide, and efforts to create more efficient and sustainable chemical processes are often stymied by cost or scale.

- Boron nitride is not well known as a catalyst, yet experiments show it is highly efficient at converting propane to propylene—one of the most widely used chemical building blocks in the world.

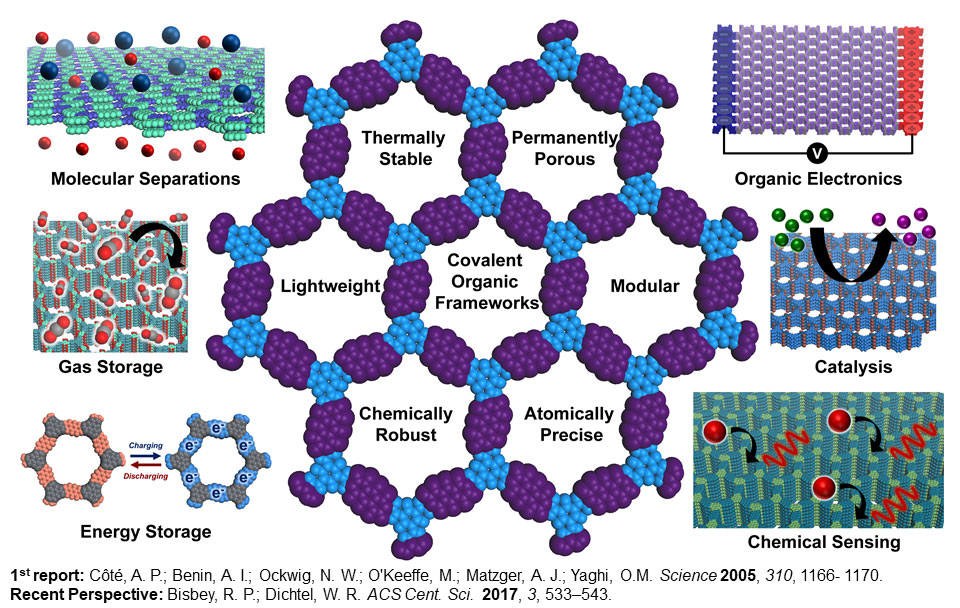

- Two-dimensional polymers called covalent organic frameworks (COFs) can be used for water filtration, energy storage, and chemical sensing.

- Until recently, researchers have struggled to control and direct COF formation, but new approaches to COF synthesis are advancing the field.

Boron Nitride: A Surprising Catalyst

Industrial chemicals “define our standard of living,” said Ive Hermans, 2019 Blavatnik National Awards Finalist, before explaining that nearly 96% of the products used in daily life arise from processes requiring bulk chemical production. These building block molecules are produced at an astonishingly large scale, using energy-intensive methods that also produce waste products, including carbon dioxide.

Despite pressure to reduce carbon emissions, the pace of innovation in chemical production is slow. The industry is capital-intensive — a chemical production plant can cost more than $2 billion—and it can take a decade or more to develop new methods of synthesizing chemicals. Concepts that show promise in the lab often fail at scale or are too costly to make the transition from lab to plant. “The goal is to come up with technologies that are both easily implemented and scalable,” Hermans said.

Catalysts are a key area of interest for improving chemical production processes. These molecules bind to reactants and can boost the speed and efficiency of chemical reactions. Hermans’ research focuses on catalyst design, and one of his recent discoveries, made “just by luck,” stands to transform production of one of the most in-demand chemicals worldwide—propylene.

Historically, propylene was one product (along with ethylene and several others) produced by “cracking” carbon–carbon bonds in naphtha, a crude oil component that has since been replaced by ethane (from natural gas) as a preferred starting material. However, ethane yields far less propylene, leaving manufacturers and researchers to seek alternative methods of producing the chemical.

Enter boron nitride, a two-dimensional material whose catalytic properties took Hermans by surprise when a student in his lab discovered its efficiency at converting propane, also a component of natural gas, to propylene. Existing methods for running this reaction are endothermic and produce significant CO2. Boron nitride catalysts facilitate an exothermic reaction that can be conducted at far cooler temperatures, with little CO2 production. Better still, the only significant byproduct is ethylene, an in-demand commodity.

Hermans sees this success as a step toward a more sustainable future, where chemical production moves “away from a linear economy approach, where we make things and produce CO2 as a byproduct, and more toward a circular economy where we use different starting materials and convert CO2 back into chemical building blocks.”

Polymerization in Two Dimensions

William Dichtel, a Blavatnik National Awards Finalist in 2017 and 2019, offered an update from one of the most exciting frontiers in polymer chemistry—two-dimensional polymerization. The synthetic polymers that dominate modern life are comprised of linear, repeating chains of linked building blocks that imbue materials with specific properties. Designing non-linear polymer architectures requires the ability to precisely control the placement of components, a feat that has challenged chemists for a decade.

Dichtel described the potential of a class of polymers called covalent organic frameworks, or COFs—networks of polymers that form when monomers are polymerized into well-defined, two-dimensional structures. COFs can be created in a variety of topologies, dictated by the shape of the monomers that comprise it, and typically feature pores that can be customized to perform a range of functions. These materials hold promise for applications including water purification membranes, energy and gas storage, organic electronics, and chemical sensing.

Dichtel explained that COF development is a trial and error process that often fails, as the mechanisms of their formation are not well understood. “We have very limited ability to improve these materials rationally—we need to be able to control their form so we can integrate them into a wide variety of contexts,” he said.

A breakthrough in COF synthesis came when chemist Brian Smith, a former postdoc in Dichtel’s lab, discovered that certain solvents allowed COFs to disperse as nanoparticles in solution rather than precipitating as powder. These particles became the basis for a new method of growing large, controlled crystalline COFs using nanoparticles as structural “seeds,” then slowly adding monomers to maximize growth while limiting nucleation. “This level of control parallels living polymerization, with well-defined initiation and growth phases,” Dichtel said.

More recently, Dichtel’s group has made significant advances in COF fabrication, successfully casting them into thin films that could be used in membrane and filtration applications.

Further Readings

Hermans

Zhang Z, Jimenez-Izal E, Hermans I, Alexandrova AN.

J Phys Chem Lett. 2019 Jan 3;10(1):20-25.

Love AM, Thomas B, Specht SE, et al.

Probing the Transformation of Boron Nitride Catalysts under Oxidative Dehydrogenation Conditions.

J Am Chem Soc. 2019 Jan 9;141(1):182-190.

Dichtel

Côté AP, Benin AI, Ockwig NW, et al.

Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks.

Science. 2005 Nov 18;310(5751):1166-70.

Bisbey RP, Dichtel WR.

Covalent Organic Frameworks as a Platform for Multidimensional Polymerization.

ACS Cent Sci. 2017 Jun 28;3(6):533-543.

Mulzer CR, Shen L, Bisbey RP, et al.

ACS Cent Sci. 2016 Sep 28;2(9):667-673.

Ji W, Xiao L, Ling Y, et al.

J Am Chem So

Smith BJ, Parent LR, Overholts AC, et al.

Colloidal Covalent Organic Frameworks.

ACS Cent Sci. 2017 Jan 25;3(1):58-65.

Li H. Evans AM, Castano I, et al.

Nucleation-Elongation Dynamics of Two-Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks.

ChemRxiv, 2019.

Advances in Neuroscience

Speakers

Michal Rivlin

Weizmann Institute of Science

Nieng Yan

Princeton University

Highlights

- The 80 subtypes of retinal ganglion cells each encode different aspects of vision, such as direction and motion.

- The “preferences” of these cells were believed to be hard-wired, yet experiments show that retinal ganglion cells can be reprogrammed by exposure to repetitive stimuli.

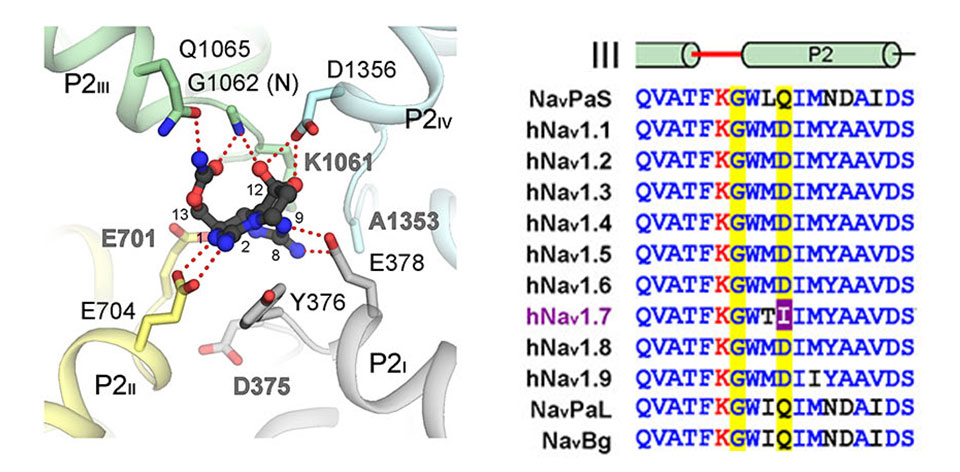

- Sodium ion channels control electrical signaling in cells of the heart, muscles, and brain, and have long been drug targets due to their connection to pain signaling.

- Cryo-electron microscopy has allowed researchers to visualize Nav 7, a sodium ion channel implicated in pain syndromes, and to identify molecules that interfere with its function.

Retinal Computations: Recalculating

The presentation from Michal Rivlin, the Life Sciences Laureate of the 2019 Blavatnik Awards in Israel, began with an optical illusion, a dizzying exercise during which a repetitive, unidirectional pattern of motion appeared to rapidly reverse direction. “You probably still perceive motion, but the image is actually stable now,” Rivlin said, completing a powerful demonstration of the action of direction-sensitive retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), whose mechanisms she has studied for more than a decade. The approximately 80 subtypes of RGCs each encode a different aspect, or modality of vision—motion, color, and edges, as well as perception of visual phenomena such as direction. These modalities are hard-wired into the cells and were thought to be immutable—a retinal ganglion cell that perceived left-to-right motion was thought incapable of responding to visual signals that move right-to-left. Rivlin’s research has challenged not only this notion, but also many other beliefs about the function and capabilities of the retina.

Rather than simply capturing discrete aspects of visual information like a camera and relaying that information to the visual thalamus for processing, the cells of the retina actually perform complex processing functions and display a surprising level of plasticity. Rivlin’s lab is probing both the anatomy and functionality of various types of retinal ganglion cells, including those that demonstrate selectivity, such as a preference for movement in one direction or attunement to increases or decreases in illumination. By exposing these cells to various repetitive stimuli, Rivlin has shown that the selectivity of RGCs can be reversed, even in adult retinas.

These dynamic changes in cells whose preferences were believed to be singular and hard-wired have implications not just for understanding retinal function but for understanding the physiological basis of visual perception. Stimulus-dependent changes in the coding of retinal ganglion cells also have downstream impacts on the visual thalamus, where retinal signals are processed. This unexpected plasticity in retinal cells has led Rivlin and her collaborators to investigate the possibility that the visual thalamus and other parts of the visual system might also display greater plasticity than previously believed.

Targeting Sodium Channels for Pain Treatment

Nature’s deadliest predators may seem an unlikely inspiration for developing new analgesic drugs, but as Nieng Yan, 2019 Blavatnik National Awards Finalist, explained, the potent toxins of some snails, spiders, and fish are the basis for research that could lead to safer alternatives to opioid medications.

Voltage-gated ion channels are responsible for electrical signaling in cells of the brain, heart, and skeletal muscles. Sodium channels are one of many ion channel subtypes, and their connection to pain signaling is well documented. Sodium channel blockers have been used as analgesics for a century, but they can be dangerously indiscriminate, inhibiting both the intended channel as well as others in cardiac or muscle tissues. The development of highly selective small molecules capable of blocking only channels tied to pain signaling seemed nearly impossible until two breakthroughs—one genetic, the other technological—brought a potential path for success into focus.

A 2006 study of families with a rare genetic mutation that renders them fully insensitive to pain turned researchers’ focus to the role of the gene SCN9A, which codes for the voltage-gated sodium ion channel Nav 1.7, in pain syndromes. Earlier studies showed that overexpression of SCN9A caused patients to suffer extreme pain sensitivity, and it was now clear that loss of function mutations resulted in the opposite condition.

As Yan explained, understanding this channel required the ability to resolve its structure, but imaging techniques available at that time were poorly suited to large, membrane-bound proteins. With the advent of cryo-electron microscopy, Yan and other researchers have not only resolved the structure of Nav 1.7, but also characterized small molecules—mostly derived from animal toxins—that precisely and selectively interfere with its function. Developing synthetic drugs based on these molecules is the next phase of discovery, and it’s one that may happen more quickly than expected. “When I started my lab, I thought resolving this protein’s structure would be a lifetime project, but we shortened it to just five years,” said Yan.

Further Readings

Rivlin

Warwick RA, Kaushansky N, Sarid N, et al.

Inhomogeneous Encoding of the Visual Field in the Mouse Retina.

Curr Biol. 2018 Mar 5;28(5):655-665.e3

Rivlin-Etzion M, Grimes WN, Rieke F.

Flexible Neural Hardware Supports Dynamic Computations in Retina.

Trends Neurosci. 2018 Apr;41(4):224-237.

Vlasits AL, Bos R, Morrie RD, et al.

Visual stimulation switches the polarity of excitatory input to starburst amacrine cells.

Neuron. 2014 Sep 3;83(5):1172-84.

Rivlin-Etzion M, Wei W, Feller MB.

Visual stimulation reverses the directional preference of direction-selective retinal ganglion cells.

Neuron. 2012 Nov 8;76(3):518-25.

Yan

Shen H, Liu D, Wu K, et al.

Structures of human Nav1.7 channel in complex with auxiliary subunits and animal toxins.

Science. 2019 Mar 22;363(6433):1303-1308.

Pan X, Li Z, Huang X, et al.

Molecular basis for pore blockade of human Na+ channel Nav1.2 by the μ-conotoxin KIIIA.

Science. 2019 Mar 22;363(6433):1309-1313.

Pan X, Li Z, Zhou Q, et al.

Structure of the human voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.4 in complex with β1.

Science. 2018 Oct 19;362(6412).

Shen H, Li Z, Jiang Y, et al.

Structural basis for the modulation of voltage-gated sodium channels by animal toxins.

Science. 2018 Oct 19;362(6412).

Computer Science

Speakers

Jure Leskovec

Stanford University

Elza Erkip

New York University

Highlights

- A novel approach to developing machine learning algorithms has improved applications for non-linear datasets.

- Neural networks can now be used for complex predictive tasks, including forecasting polypharmacy side effects.

- 5G wireless networks will expand the capabilities of internet-connected devices, providing dramatically faster data transmission and increased reliability.

- Tools used to design wireless networks can also be used to understand vulnerabilities in the design of online platforms and social networks, particularly as it pertains to user privacy and data anonymization.

Machine Learning with Networks

“For the first time in history, we are using computers to process data at scale to gain novel insights,” said Jure Leskovec, a Blavatnik National Awards Finalist in 2017, 2018, and 2019, describing one aspect of the digital transformation of science, technology, and society. This shift, from using computers to run calculations or simulations to using them to generate insights, is driven in part by the massive data streams available from the Internet and internet-connected devices. Machine learning has catalyzed this transformation, allowing researchers to not only glean useful information from large datasets, but to make increasingly reliable predictions based on it. Just as new imaging techniques reveal previously unknown structures and phenomena in biology, astronomy, and other fields, so too are big data and machine learning bringing previously unobservable models, signals, and patterns to the surface.

This “new paradigm for discovery” has limitations, as Leskovec explained. Machine learning has advanced most rapidly in areas where data can be represented as simple sequences or grids, such as computer vision, image analysis, and speech processing. Analysis of more complex datasets—represented by networks rather than linear sequences—was beyond the scope of neural networks until recently, when Leskovec and his collaborators approached the challenge from a different angle.

The team considered networks as computation graphs, recognizing that the key to making predictions was understanding how information propagates across the network. By training each node in the network to collect information about neighboring nodes and aggregating the resulting data, they can use node-level information to make predictions within the context of the entire network.

Leskovec shared two case studies demonstrating the broad applicability of this approach. In healthcare, a neural network designed by Leskovec is identifying previously undocumented side effects from drug-drug interactions. Each network node represents a drug or a protein target of a drug, with links between the nodes emerging based on shared side effects, protein targets, and protein-protein interactions. This type of polydrug side effects analysis is infeasible through clinical trials, and Leskovec is working to optimize it as a point-of-care tool for clinicians.

A similar system has been deployed on the online platform Pinterest, where Leskovec serves as Chief Scientist. It has improved the site’s ability to classify users’ preferences and suggest additional content. “We’re generalizing deep learning methodologies to complex data types, and this is leading to new frontiers,” Leskovec said.

Understanding and Engineering Communications Networks

Elza Erkip has never seen a slide rule. In two decades as a faculty researcher and electrical and computer engineer, Erkip, 2010 Blavatnik Awards Finalist, has corrected her share of misconceptions about her field, and about the role of engineering among the scientific disciplines. She joked about stereotypes portraying engineers—most of them men—wielding slide rules or wearing hard hats, but emphasized the importance of raising awareness about the real-life work of engineers. “Scientists want to understand the universe, but engineers use existing scientific knowledge to design and build things,” she explained. “We contribute to discovery, but mostly we want to solve problems, to find solutions that work in the real world.”

Erkip focuses on one of the most impactful areas of 21st century living—wireless communication—and the ever-evolving suite of technologies that support it. She reviewed the rapid progression of wireless device capabilities, from phones that featured only voice calling and text messaging, through the addition of Wi-Fi capability and web browsing, all the way to the smartphones of today, which boast more computing power than the Apollo 11 spacecraft that landed on the moon. She described the next revolution in wireless—5G networks and devices—which promises higher data rates and significant increases in speed and reliability. Tapping the millimeter-wave bands of the electromagnetic spectrum, 5G will rely on different wireless architectures featuring massive arrays of small antennae, which are better suited to propagating shorter wavelengths. The increased bandwidth will enable many more devices to come online. “It won’t just be humans communicating—we’ll have devices communicating with each other,” Erkip said, describing the future connectivity between robots, autonomous cars, home appliances, and sensors embedded in transportation, manufacturing, and industrial equipment.

Erkip also discussed the application of tools used to understand and build wireless networks to gain insight into privacy issues within social networks. De-anonymization of user data has long plagued online platforms. Studies have shown that it’s often possible to identify and match users across multiple social platforms or databases using publicly available information—a breach that has greater implications for a database of health or voting records than it does for a consumer-oriented site such as Netflix. Erkip is working to understand the fundamental properties of these networks to elucidate the factors that predispose them to de-anonymization attacks.

Further Readings

Leskovec

Zitnik M, Agrawal M, Leskovec J.

Modeling polypharmacy side effects with graph convolutional networks.

Bioinformatics. 2018 Jul 1;34(13):i457-i466.

Ying R, He R, Chen K, et al.

Graph Convolutional Neural Networks for Web-Scale Recommender Systems.

KDD. 2018.

Erkip

Shirani F, Garg S, Erkip E.

A Concentration of Measure Approach to Database De-anonymization.

IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory. 2019.

Shirani F, Garg S, Erkip E.

Optimal Active social Network De-anonymization Using Information Thresholds.

IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory. 2018.

Materials Science

Speakers

Chiara Daraio

Caltech

Liangbing Hu

University of Maryland, College Park

Highlights

- Computer-aided manufacturing is enabling researchers to design materials with precisely tuned properties, such as responsiveness to light, temperature, or moisture.

- Structured materials can mimic robots or machines, changing shape and form repeatedly in the presence of various stimuli.

- Ultra-strong, lightweight wood-based materials made of nanocellulose fibers may one day resolve some of the world’s most pressing challenges in water, energy and sustainability, replacing transparent plastic packaging, window glass, and even steel and other alloys in vehicles and buildings.

Mechanics of Robotic Matter

Chiara Daraio’s work challenges the traditional definition of words like material, structure, and robot. Working at the intersection of physics, materials science, and computer science, she designs materials with novel properties and functionalities, enabled by computer-aided design and 3D fabrication. Rather than considering a material as the foundation for assembling a structure, Daraio, 2019 Blavatnik National Awards Finalist, designs materials with intricate structures in unique and complex geometries.

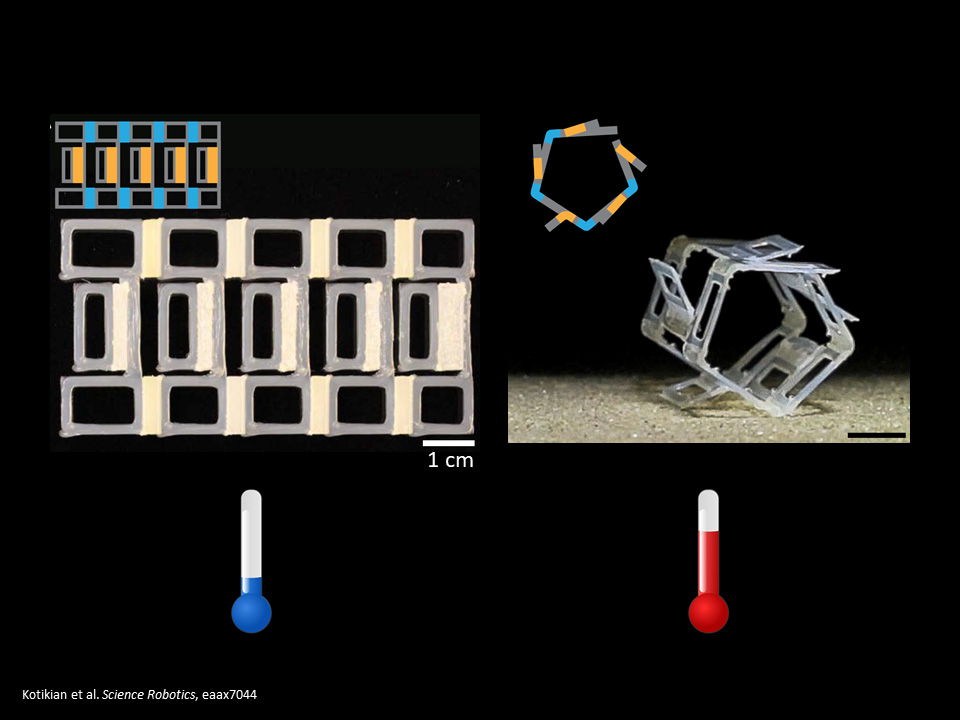

Daraio demonstrated a series of responsive materials—those that morph in the presence of stimuli such as temperature, light, moisture, or salinity. In their simplest forms, these materials change shape—a piece of heat-responsive material folds and unfolds as air temperature changes, or a leaf-shaped hydro-sensitive material opens and closes as it transitions from wet to dry. In more complex forms, materials can display time-dependent responses, as shown in a video demonstration of a row of polymer strips changing shape at different rates, depending on their thickness. Daraio showed how computer-graphical approaches allow researchers to design a single material with different properties in different regions, allowing complex actuation in a time-dependent manner, such as a polymer “flower” with interconnecting leaves taking shape and a polymer “ribbon” slowly interweaving a knot.

Conventional ideas dictate that a robot is a programmable machine capable of completing a task. “But what if the material is the machine?” asked Daraio, showing the remarkable capabilities of a thin liquid crystal elastomer foil composed of one heat-sensitive and one cold-sensitive material. At room temperature, the foil is flat. Heat from a warm table causes it to curl upward, turn over, and “walk” forward. “As long as there’s some kind of external environmental stimulus, we can design a material that can repeatedly perform actions in time,” Daraio said. Similar responsive materials have been used in a self-deploying solar panel that [remove folds and] unfolds in response to heat.

Materials have been “the seeds of technological innovation” throughout human history, and Daraio believes that structured materials will enable new functionalities at the macroscale—for use in wearables such as helmets as well as in smart building technologies—and at the microscale, where responsive materials could be used for medical diagnostics or drug delivery.

Sustainable Applications for Wood Nanotechnologies

Wood, glass, plastic, and steel are among the most ubiquitous materials on Earth, and Liangbing Hu, 2019 Blavatnik National Awards Finalist, is rethinking them all. Inspired by the global need to develop sustainable materials, Hu turned to the most plentiful source of biomass on Earth— trees—to create a new generation of wood-based materials with astonishing properties. Hu relies on nanocellulose fibers, which can be engineered to serve as alternatives to commonly used unsustainable or energy-intensive materials.

Hu introduced a transparent film that could pass for plastic and can be used for packaging, yet is ten times stronger and far more versatile. This transparent nanopaper, made of nanocellulose fibers, could also be used as a display material in flexible electronics or as a photonic overlay that boosts the efficiency of solar cells by 30%.

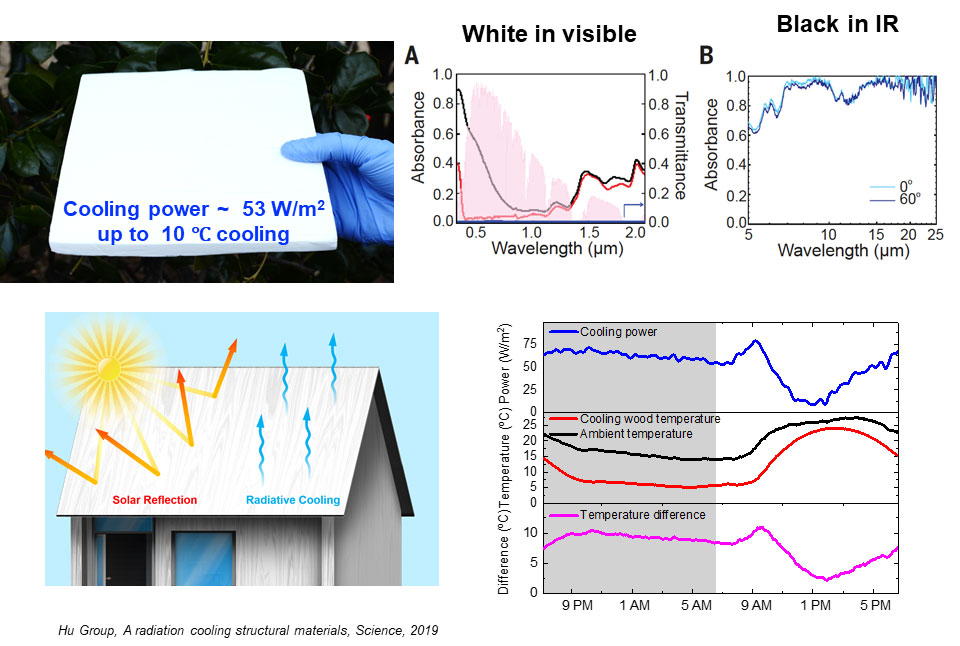

Hu has also tested transparent wood—a heavier-gauge version of nanopaper made by removing lignin from wood and injecting the channels with a clear polymer—as an energy-saving building material. More than half of home energy loss is due to poor wall insulation and leakage through window glass. By Hu’s calculations, replacing glass windows with transparent wood would also provide a six-fold increase in thermal insulation. Pressed, delignified wood has also proven to be a superior material for wall insulation. Used on roofs, it is a highly efficient means of passive cooling—the material absorbs heat and then re-radiates it, cooling the surface below it by about ten degrees.

Comparisons of mechanical strength between wood and steel are almost laughable, unless the wood is another of Hu’s creations—the aptly named “superwood.” Delignified and compressed to align the nanocellulose fibers, even inexpensive woods become thinner and 10-20 times stronger. Superwood rivals steel in strength and durability, and could become a viable alternative to steel and other alloys in buildings, vehicles, trains, and airplanes. Sustainable sourcing would eliminate pollution and carbon dioxide associated with steel production, and its lightweight profile could drastically improve vehicle fuel efficiency.

Further Readings

Daraio

Celli P, McMahan C, Ramirez B, et al.

Shape-morphing architected sheets with non-periodic cut patterns.

Soft Matter. 2018 Dec 12;14(48):9744-9749.

Chen T, Bilal OR, Shea K, Daraio C.

Harnessing bistability for directional propulsion of soft, untethered robots.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018 May 29;115(22):5698-5702.

Bauhofer AA, Krödel S, Rys J, et al.

Harnessing Photochemical Shrinkage in Direct Laser Writing for Shape Morphing of Polymer Sheets.

Adv Mater. 2017 Nov;29(42).

Hu

Song J, Chen C, Zhu S, et al.

Processing bulk natural wood into a high-performance structural material.

Nature. 2018 Feb 7;554(7691):224-228.

Huang J, Zhu H, Chen Y, et al.

Highly transparent and flexible nanopaper transistors.

ACS Nano. 2013 Mar 26;7(3):2106-13.

Huang J, Zhu H, Chen Y, et al.

Novel nanostructured paper with ultrahigh transparency and ultrahigh haze for solar cells.

Nano Lett. 2014 Feb 12;14(2):765-73.

Zhu M, Song J, Li T, et al.

Highly Anisotropic, Highly Transparent Wood Composites.

Adv Mater. 2016 Jul;28(26):5181-7.

Li T, Zhai Y, He S, et al.

A radiative cooling structural material.

Science. 2019 May 24;364(6442):760-763.

Zhu H, Luo W, Ciesielski PN, et al.

Wood-Derived Materials for Green Electronics, Biological Devices, and Energy Applications.

Chem Rev. 2016 Aug 24;116(16):9305-74.

Medicine and Medical Diagnostics

Speakers

Nicholas Navin

MD Anderson Cancer Center

Wei Min

Columbia University

Highlights

- Tumor cells are genetically heterogeneous, complicating efforts to sequence DNA from tumor tissue samples.

- Techniques for isolating and sequencing single-cell samples have transformed the study of cancer genetics.

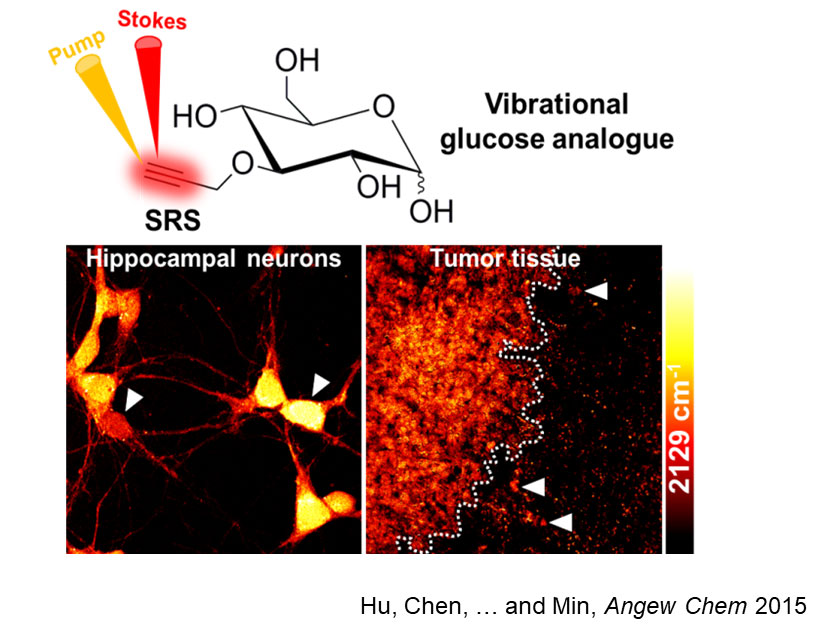

- Stimulated Ramen scattering, a non-invasive imaging technique, can visualize processes including glucose uptake and fatty acid metabolism within living cells.

Single Cell Genomics: A Revolution in Cancer Biology

Nicholas Navin, 2019 Blavatnik National Awards Finalist, doesn’t use the word “revolution” lightly, but when it comes to the field of single-cell genomics and its impact on cancer research, he stands by the term. Over the past ten years, DNA sequencing of single tumor cells has led to major discoveries about the progression of cancer and the process by which cancer cells resist treatment.

Unlike healthy tissue cells, tumor cells are characterized by genomic heterogeneity. Samples from different areas of the same tumor often contain different mutations or numbers of chromosomes. This diversity has long piqued researchers’ curiosity. “Is it stochastic noise generated as tumor cells acquire different mutations, or could this diversity be important for resistance to therapy, invasion, or metastasis?” Navin asked.

Answering that question required the ability to do comparative studies of single tumor cells, a task that was long out of reach. DNA sequencing technologies historically required a large sample of genetic material—a tricky proposition when sampling a highly diverse population of tumor cells. Some mutations, which could drive invasion or resistance, may be present in just a few cells and thus not be represented in the results. Navin was part of the first team to develop a method for excising a single cancer cell from a tumor, amplifying the DNA, and producing an individualized genetic sequence. As amplification and sequencing methods have improved, so too have the insights gleaned from single-cell genomic studies, which Navin likens to “paleontology in tumors”—the notion that a sample taken at a single point in time can allow researchers to make inferences about tumor evolution.

Single-cell studies have contradicted the idea of a stepwise evolution of cancer cells, with one mutation leading to another and ultimately tipping the scales toward malignancy. Instead, Navin’s studies reveal a punctuated evolution, whereby many cells simultaneously become genetically unstable. Longitudinal studies of single-cell samples in patients with triple-negative breast cancer are beginning to answer questions about how cancer cells evade treatment, showing that cells that survive chemotherapy have innate resistance, and then undergo further transcriptional changes during treatment, which increase resistance.

Translating these findings to the clinic is a longer-term process, but Navin envisions single-cell genomics will significantly impact strategies for targeted therapy, non-invasive monitoring, and early cancer detection.

Chemical Imaging in Biomedicine

Wei Min, a Blavatnik Awards Finalist in 2012 and 2019, concluded the session with a visually striking glimpse into the world of stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy. This noninvasive imaging technique provides both sub-cellular resolution and chemical information about living cells, while transcending some of the limitations of fluorescence-based optical microscopy. The probes used to tag molecules for fluorescent imaging can alter or destroy small molecules of interest, including glucose, lipids, amino acids, or neurotransmitters. Rather than using tags, SRS builds on traditional Raman spectroscopy, which captures and analyzes light scattered by the unique vibrational frequencies between atoms in biomolecules. The original method, first pioneered in the 1930s, is slow and lacks sensitivity, but in 2008, Min and others improved the technique.

SRS has since become a leading method for label-free visualization of living cells, providing an unprecedented window into cellular activities. Using SRS and a variety of custom chemical tags—“vibrational tags,” as Min described them—bound to biomolecules such as DNA or RNA bases, amino acids, or even glucose, researchers can observe the dynamics of biological functions. SRS has visualized glucose uptake in neurons and malignant tumors, and has been used to observe fatty acid metabolism, a critical step in understanding lipid disorders. Imaging small drug molecules is notoriously difficult, but Min reported the results of experiments using SRS to tag therapeutic drug molecules and study their activity within tissues.

A recent breakthrough in SRS technology involves pairing it with Raman dyes to break the “color barrier” in optical imaging. Due to the width of the fluorescent spectrum, labels are limited to five or six colors per sample, which prevents researchers from imaging many structures within a tissue sample simultaneously. Min has introduced a hybrid imaging technique that allows for super-multiplexed imaging—up to 10 colors in a single cell image—and utilizes a dramatically expanded palette of Raman frequencies that yield at least 20 distinct colors.

Further Readings

Navin

Kim C, Gao R, Sei E, et al.

Chemoresistance Evolution in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Delineated by Single-Cell Sequencing.

Cell. 2018 May 3;173(4):879-893.e13.

Casasent AK, Schalck A, Gao R, et al.

Multiclonal Invasion in Breast Tumors Identified by Topographic Single Cell Sequencing.

Cell. 2018 Jan 11;172(1-2):205-217.e12.

Gao R, Davis A, McDonald TO, et al.

Punctuated copy number evolution and clonal stasis in triple-negative breast cancer.

Nat Genet. 2016 Oct;48(10):1119-30.

Wang Y, Navin NE.

Advances and applications of single-cell sequencing technologies.

Mol Cell. 2015 May 21;58(4):598-609.

Wang Y, Waters J, Leung ML, et al.

Clonal evolution in breast cancer revealed by single nucleus genome sequencing.

Nature. 2014 Aug 14;512(7513):155-60.

Min

Xiong H, Shi L, Wei L, et al.

Stimulated Raman excited fluorescence spectroscopy and imaging.

Nat Photonics. 2019; (3) 412–417.

Xiong H, Qian N, Miao Y, et al.

Stimulated Raman Excited Fluorescence Spectroscopy of Visible Dyes.

J Phys Chem Lett. 2019 Jul 5;10(13):3563-3570.

Zhang L, Shi L, Shen Y, et al.

Spectral tracing of deuterium for imaging glucose metabolism.

Nat Biomed Eng. 2019 May;3(5):402-413.

Wei M, Shi L, Shen Y, et al.

Volumetric chemical imaging by clearing-enhanced stimulated Raman scattering microscopy.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Apr 2;116(14):6608-6617.

Shi L, Zheng C, Shen Y, et al.

Optical imaging of metabolic dynamics in animals.

Nat Commun. 2018 Aug 6;9(1):2995.