The globalization of universities must be embraced, not feared, in order to advance STEM research internationally and empower the next generation.

Published March 1, 2010

By Ben Wildavsky

For several years now—and not for the first time in our nation’s history—CEOs, politicians, and education leaders have regularly decried the shortcomings of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education in America’s elementary and secondary schools. And they have vigorously promoted a reform agenda aimed at tackling those problems.

But what about our colleges and universities? On the one hand, America’s research universities are universally acknowledged as the world’s leaders in science and engineering, unsurpassed since World War II in the sheer volume and excellence of the scholarship and innovation they generate. On the other, there are signs that the rest of the world is gaining on us fast—building new universities, improving existing ones, competing hard for the best students, and recruiting U.S.-trained PhDs to return home to work in university and industry labs. Should we be worried?

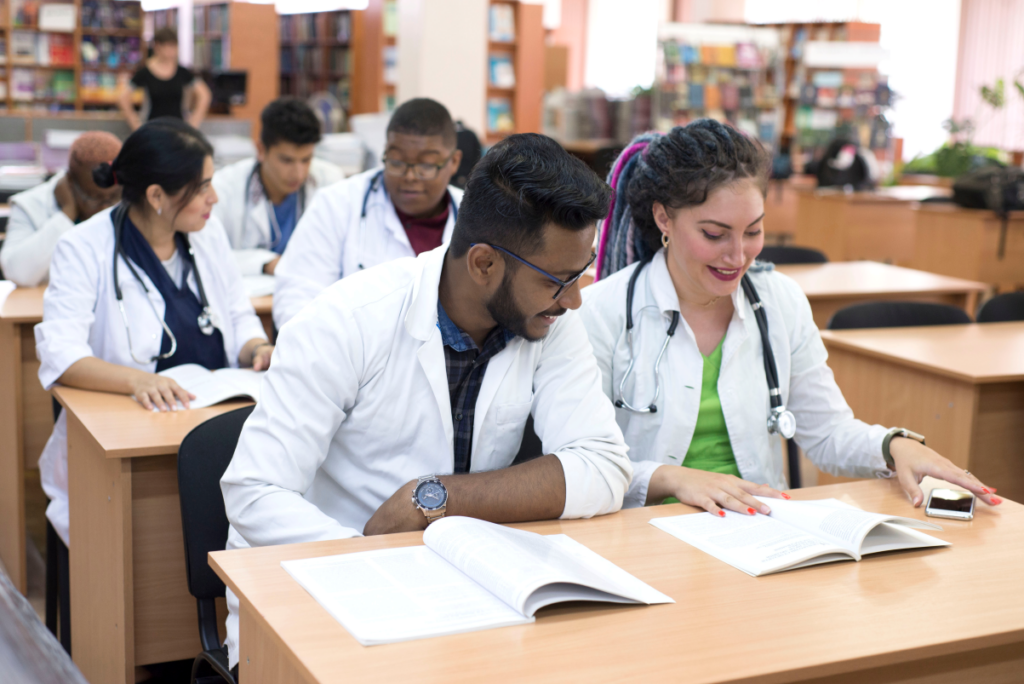

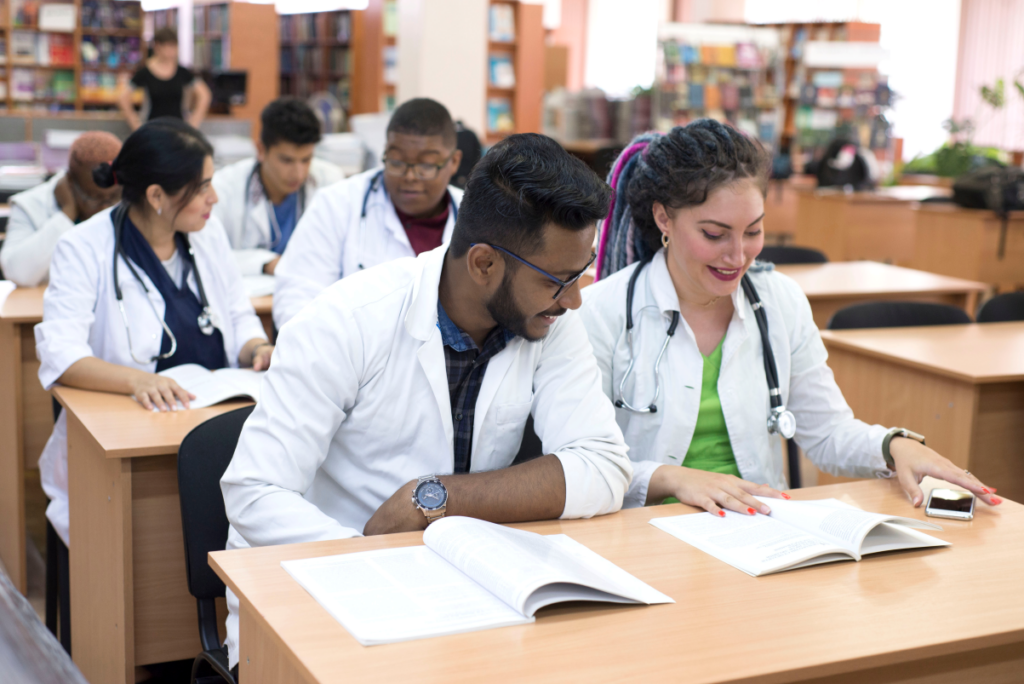

There is no question that the academic enterprise has become increasingly global, particularly in the sciences. Overall, nearly three million students now study outside their home nations—a 57 percent increase in the last decade. In the United States, by far the largest magnet for students from overseas, foreign students now dominate doctoral programs in STEM fields, constituting, for example, 65 percent, 64 percent, and 56 percent, respectively, of PhDs in computer science, engineering, and physics. Tsinghua and Peking universities together recently surpassed Berkeley as the top sources of students who go on to earn American PhD’s.

A Race to Create World Class Universities

Faculty are on the move, too: Half the world’s top physicists no longer work in their native countries. And major institutions such as New York University and the University of Nottingham are creating branch campuses in the Middle East and Asia—there are now 162 satellite campuses worldwide, an increase of 43 percent in just the past three years. At the same time, growing numbers of traditional student “sender” nations, from South Korea, China, and Saudi Arabia to France and Germany, are trying to improve both the quantity and the quality of their own degrees, engaging in a fierce—and expensive—race to create world-class research universities.

All this competition has led to considerable handwringing. During a 2008 campaign stop, for instance, then-candidate Barack Obama spoke in alarmed tones about the threat such academic competition poses to the United States. “If we want to keep on building the cars of the future here in America,” he declared, “we can’t afford to see the number of PhD’s in engineering climbing in China, South Korea, and Japan even as it’s dropped here in America.”

Nor are such concerns limited to the U.S. Beyond anxious rhetoric, in a number of nations worries about brain drain and educational competition have led to outright academic protectionism. India and China are notorious for the legal and bureaucratic obstacles they erect to West-ern universities wishing to set up satellite campuses catering to local students. And some countries erect barriers to students who want to leave: The president of one of the prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology effectively banned undergraduates from taking academic or business internships overseas.

Quotas on Foreign Students

Elsewhere, educators institute quotas on foreign students, as in Malaysia, which places a five percent cap on the number of foreign undergraduates who can attend the country’s public universities (just as the University of Tennessee once placed a 20 percent cap on the percentage of foreign graduate students in each department). Perhaps the silliest example of this protectionist mentality can be found in Germany, which for years prevented holders of doctorates earned outside the European Union from using the title “Dr.” Even a recent reform plan would extend that privilege only to holders of doctorates from 200 U.S. research universities and a limited number of universities in Australia, Israel, Japan, Canada, and Russia.

There are other impediments to global mobility, too, not always explicitly protectionist, but all having the de facto effect of discouraging or preventing open access to universities around the world. In the post-9/11 era, legitimate security concerns led to enormous student visa delays and bureaucratic hassles for foreigners aspiring to study in Great Britain and the United States. As the problem was recognized and visa processing was streamlined, international student numbers rebounded and eventually increased.

By 2009, however, visa delays became common again, particularly for graduate and postdoctoral students in science and engineering, who form the backbone of many university-based research laboratories and thus serve as key players in the U.S. drive for scientific and technical innovation. Then there are severe limits on H-1B visas, which allow highly skilled foreigners, usually in science and engineering, to work temporarily in the United States and serve as an enticement for the best and brightest to study and perhaps remain here. With just 85,000 or so H-1B visas issued each year—and permanent-resident visas for skilled workers also scarce—waiting lists are long, which sends some talented students elsewhere.

Free Trade in Mind

Perhaps some of the anxiety over the new global academic enterprise is understandable, particularly in a period of massive economic uncertainty. But setting up protectionist obstacles is a big mistake. The globalization of higher education should be embraced, not feared—including in the U.S. In the near term, it’s worth remembering that, despite the alarmism often heard about the global academic wars, U.S. dominance of the research world remains near-complete.

A RAND report found that almost two-thirds of highly cited articles in science and technology come from the U.S. Seventy percent of Nobel Prize winners are employed by U.S. universities, which lead global college rankings. And Yale president Richard Levin notes that the U.S. accounts for 40 percent of global spending on higher education.

That said, it’s quite true that other countries are scrambling to emulate the American model and to give us a run for our money. Yet there is every reason to believe that the worldwide competition for human talent, the race to produce innovative research, the push to extend university campuses to multiple countries, and the rush to produce talented graduates who can strengthen increasingly knowledge-based economies will be good for us as well. Why? First and foremost, because knowledge is not a zero-sum game. Intellectual gains by one country often benefit others.

More PhD production and burgeoning research in China, for instance, doesn’t take away from American’s store of learning—it enhances what we know and can accomplish. In fact, Chinese research may well provide the building blocks for innovation by U.S. entrepreneurs—or those from other nations. “When new knowledge is created, it’s a public good and can be used by many,” RAND economist James Hosek told the Chronicle of Higher Education.

The Economics of Global Academic Culture

Indeed, the economic benefits of a global academic culture are significant. In a recent essay, Harvard economist Richard Freeman says these gains should accrue both to the U.S. and the rest of the world. The globalization of higher education, he writes, “by accelerating the rate of technological advance associated with science and engineering and by speeding the adoption of best practices around the world…will lower the costs of production and prices of goods.”

Just as free trade in manufacturing or call-center support provides the lowest-cost goods and services, benefiting both consumers and the most efficient producers, global academic competition is making free movement of people and ideas, on the basis of merit, more and more the norm, with enormously positive consequences for individuals, for universities, and for nations. Today’s swirling patterns of mobility and knowledge transmission constitute a new kind of free trade: free trade in minds.

Still, even if the new world of academic globalization brings economic benefits, won’t it weaken American universities? Quite the contrary, says Freeman, who predicts that by educating top students, attracting some to stay, and “positioning the U.S. as an open hub of ideas and connections” for college graduates around the world, the nation can hold on to “excellence and leadership in the ‘empire of the mind’ and in the economic world more so than if it views the rapid increase in graduates overseas as a competitive threat.”

Less Angst, More Sense of Possibility

National borders simply don’t have the symbolic or practical meaning they once did, which bodes well for academic quality on all sides. Already, the degree of international collaboration on scientific papers has risen substantially. And there is early evidence that the most influential scholars are particularly likely to have international research experience: Well over half the highly cited researchers based in Australia, Canada, Italy, and Switzerland have spent time outside their home countries at some point during their academic careers, according to a 2005 study.

The United States should respond to the globalization of higher education not with angst but with a sense of possibility. Neither a gradual erosion in the U.S. market share of students nor the emergence of ambitious new competitors in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East means that American universities are on some in-evitable path to decline. There is nothing wrong with nations competing, trying to improve their citizens’ human capital and to reap the economic benefits that come with more and better education.

By eliminating protectionist barriers at home, by lobbying for their removal abroad, by continuing to recruit and welcome the best students in the world, by sending more students overseas, by fostering cross-national research collaboration, and by strengthening its own research universities in science, engineering, and other fields, the U.S. will not only sustain its own academic excellence but will continue to expand the sum total of global knowledge and prosperity.

Also read: Climate Change and Collective Action: The Knowledge Resistance Problem

About the Author

Ben Wildavsky is a senior fellow in research and policy at the Kauffman Foundation and a guest scholar at the Brookings Institution. This essay is adapted from The Great Brain Race: How Global Universities Are Reshaping the World, published by Princeton University Press.