With an infinity of universes proposed, and more than 10400 theories, is experimental proof of physical laws still feasible?

Published January 1, 2006

By Lee Smolin

For more than two hundred years, we physicists have been on a wild ride. Our search for the most fundamental laws of nature has been rewarded by a continual stream of discoveries. Each decade back to 1800 saw one or more major additions to our knowledge about motion, the nature of matter, light and heat, space and time. In the 20th century, the pace accelerated dramatically.

Then, about 30 years ago, something changed. The last time there was a definitive advance in our knowledge of fundamental physics was the construction of the theory we call the standard model of particle physics in 1973. The last time a fundamental theory was proposed that has since gotten any support from experiment was a theory about the very early universe called inflation, which was proposed in 1981.

Since then, many ambitious theories have been invented and studied. Some of them have been ruled out by experiment. The rest have, so far, simply made no contact with experiment. During the same period, almost every experiment agreed with the predictions of the standard model. Those few that didn’t produced results so surprising—so unwanted—that baffled theorists are still unable to explain them.

The Gap Between Theory and Experiment

The growing gap between theory and experiment is not due to a lack of big open problems. Much of our work since the 1970s has been driven by two big questions: 1) Can we combine quantum theory and general relativity to make a quantum theory of gravity? and 2) Can we unify all the particles and forces, and so understand them in terms of a simple and completely general law? Other mysteries have deepened, such as the question of the nature of the mysterious dark energy and dark matter.

Traditionally, physics progressed by a continual interplay of theory and experiment. Theorists hypothesized ideas and principles, which were explored by stating them in precise mathematical language. This allowed predictions to be made, which experimentalists then test. Conversely, when there is a surprising new experimental finding, theorists attempt to model it in order to test the adequacy of the current theories.

There appears to be no precedent for a gap between theory and experiment lasting decades. It is something we theorists talk about often. Some see it as a temporary lull and look forward to new experiments now in preparation. Others speak of a new era in science in which mathematical consistency has replaced experiment as the final arbiter of a theory’s correctness. A growing number of theoretical physicists, myself among them, see the present situation as a crisis that requires us to reexamine the assumptions behind our so-far unsuccessful theories.

I should emphasize that this crisis involves only fundamental physics—that part of physics concerned with discovering the laws of nature. Most physicists are concerned not with this but with applying the laws we know to under standard control myriads of phenomena. Those are equally important endeavors, and progress in these domains is healthy.

Contending Theories

Since the 1970s, many theories of unification have been proposed and studied, going under fanciful names such as preon models, technicolor, supersymmetry, brane worlds, and, most popularly, string theory. Theories of quantum gravity include twistor theory, causal set models, dynamical triangulation models, and loop quantum gravity. One reason string theory is popular is that there is some evidence that it points to a quantum theory of gravity.

One source of the crisis is that many of these theories have many freely adjustable parameters. As a result, some theories make no predictions at all. But even in the cases where they make a prediction, it is not firm. If the predicted new particle or effect is not seen, theorists can keep the theory alive by changing the value of a parameter to make it harder to see in experiment.

The standard model of particle physics has about 20 freely adjustable parameters, whose values were set by experiment. Theorists have hoped that a deeper theory would provide explanations for the values the parameters are observed to take. There has been a naive, but almost universal, belief that the more different forces and particles are unified into a theory, the fewer freely adjustable parameters the theory will have.

Parameters

This is not the way things have turned out. There are theories that have fewer parameters than the standard model, such as technicolor and preon models. But it has not been easy to get them to agree with experiment. The most popular theories, such as supersymmetry, have many more free parameters—the simplest supersymmetric extension of the standard model has 105 additional free parameters. This means that the theory is unlikely to be definitively tested in upcoming experiments. Even if the theory is not true, many possible outcomes of the experiments could be made consistent with some choice of the parameters of the theory.

String theory comes in a countably infinite number of versions, most of which have many free parameters. String theorists speak no longer of a single theory, but of a vast “landscape1” of possible theories. Moreover, some cosmologists argue for an infinity of universes, each of which is governed by a different theory.

A tiny fraction of these theories may be roughly compatible with present observation, but this is still a vast number, estimated to be greater than 10400 theories. (Nevertheless, so far not a single version consistent with all experiments has been written down.) No matter what future experiments see, the results will be compatible with vast numbers of theories, making it unlikely that any experiment could either confirm or falsify string theory.

A New Definition of Science

This realization has brought the present crisis to a head. Steven Weinberg and Leonard Susskind have argued for a new definition of science in which a theory maybe believed without being subject to a definitive experiment whose result could kill it. Some theorists even tell us we are faced with a choice of giving up string theory—which is widely believed by theorists—or giving up our insistence that scientific theories must be testable. As Steven Weinberg writes in a recent essay: [2]

Most advances in the history of science have been marked by discoveries about nature, but at certain turning points we have made discoveries about science itself…Now we may be at a new turning point, a radical change in what we accept as a legitimate foundation for a physical theory…The larger the number of possible values of physical parameters provided by the string landscape, the more string theory legitimates anthropic reasoning as a new basis for physical theories: Any scientists who study nature must live in a part of the landscape where physical parameters take values suitable for the appearance of life and its evolution into scientists.

An Infinity of Theories

Among an infinity of theories and an infinity of universes, the only predictions we can make stem from the obvious fact that we must live in a universe hospitable to life. If this is true, we will not be able to subject our theories to experiments that might either falsify or count as confirmation of them. But, say some proponents of this view, if this is the way the world is, it’s just too bad for outmoded ways of doing science. Such a radical proposal by such justly honored scientists requires a considered response.

I believe we should not modify the basic methodological principles of science to save a particular theory—even a theory that the majority of several generations of very talented theorists have devoted their careers to studying. Science works because it is based on methods that allow well-trained people of good faith, who initially disagree, to come to consensus about what can be rationally deduced from publicly available evidence. One of the most fundamental principles of science has been that we only consider as possibly true those theories that are vulnerable to being shown false by doable experiments.

Contending Styles of Research

I think the problem is not string theory, per se. It goes deeper, to a whole methodology and style of research. The great physicists of the beginning of the 20th century—Einstein, Bohr, Mach, Boltzmann, Poincare, Schrodinger, Heisenberg—thought of theoretical physics as a philosophical endeavor. They were motivated by philosophical problems, and they often discussed their scientific problems in the light of a philosophical tradition in which they were at home. For them, calculations were secondary to a deepening of their conceptual understanding of nature.

After the success of quantum mechanics in the 1920s, this philosophical way of doing theoretical physics gradually lost out to a more pragmatic, hard-nosed style of research. This is not because all the philosophical problems were solved: to the contrary, quantum theory introduced new philosophical issues, and the resulting controversy has yet to be settled. But the fact that no amount of philosophical argument settled the debate about quantum theory went some way to discrediting the philosophical thinkers.

It was felt that while a philosophical approach may have been necessary to invent quantum theory and relativity, thereafter the need was for physicists who could work pragmatically, ignore the foundational problems, accept quantum mechanics as given, and go on to use it. Those who either had no misgivings about quantum theory or were able to put their misgivings to one side were able in the next decades to make many advances all over physics, chemistry, and astronomy.

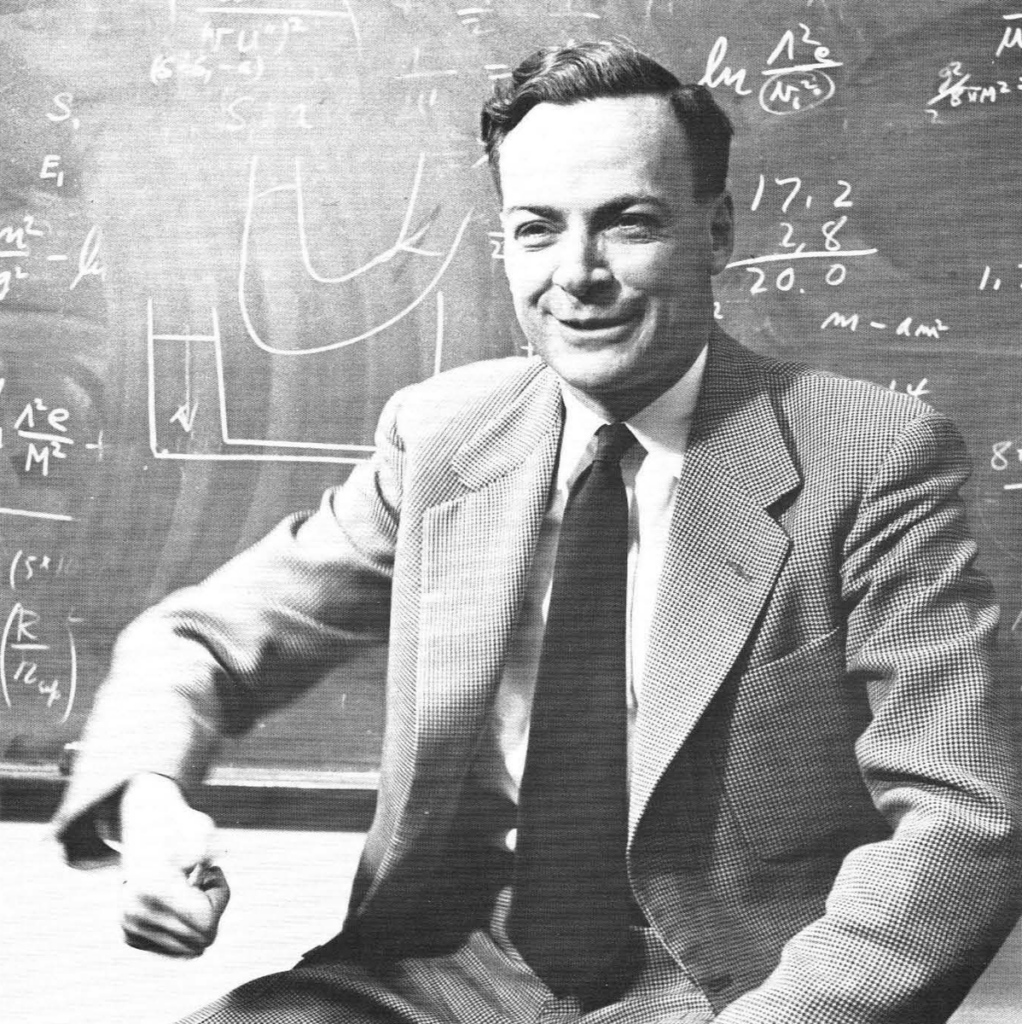

The shift to a more pragmatic approach to physics was completed when the center of gravity of physics moved to the United States in the 1940s. Feynman, Dyson, Gell-Mann, and Oppenheimer were aware of the unsolved foundational problems, but they taught a style of research in which reflection on them had no place in research.

Physics in the 1970s

By the time I studied physics in the 1970s, the transition was complete. When we students raised questions about foundational issues, we were told that no one understood them, but it was not productive to think about that. “Shut up and calculate,” was the mantra. As a graduate student, I was told by my teachers that it was impossible to make a career working on problems in the foundations of physics. My mentors pointed out that there were no interesting new experiments in that area, whereas particle physics was driven by a continuous stream of new experimental discoveries. The one foundational issue that was barely tolerated, although discouraged, was quantum gravity.

This rejection of careful foundational thought extended to a disdain for mathematical rigor. Our uses of theories were based on rough-and-ready calculation tools and intuitive arguments. There was in fact good reason to believe that the standard model of particle physics is not mathematically consistent at a rigorous level. As a graduate student at Harvard, I was taught not to worry about this because the contact with experiment was more important. The fact that the predictions were confirmed meant that something was right, even if there might be holes in the mathematical and conceptual foundations, which someone would have to fix later.

The Disappearance of Contact with Experiment

In retrospect, it seems likely that this style of research, in which conceptual puzzles and issues of mathematical rigor were ignored, can only succeed if it is tightly coupled to experiment. When the contact with experiment disappeared in the 1980s, we were left with an unprecedented situation.

The string theories are understood, from a mathematical point of view, as badly as the older theories, and most of our reasoning about them is based on conjectures that remain unproven after many years, at any level of rigor. We do not even have a precise definition of the theory, either in terms of physical principles or mathematics. Nor do we have any reasonable hope to bring the theory into contact with experiment in the foreseeable future. We must ask how likely it is that this style of research can succeed at its goal of discovering new laws of nature.

It is difficult to find yourself in disagreement with the majority of your scientific community, let alone with several heroes and role models. But after a lot of thought I’ve come to the conclusion that the pragmatic style of research is failing. By 1980, we had probably gone as far as we could by following this pragmatic, antifoundational methodology.

If we have failed to solve the key problems of quantum gravity and unification in a way that connects to experiment, perhaps these problems cannot be solved using the style of research that we theoretical physicists have become accustomed to. Perhaps the problems of unification and quantum gravity are entangled with the foundational problems of quantum theory, as Roger Penrose and Gerard t’Hooft think. If they are right, thousands of theorists who ignore the foundational problems have been wasting their time.

Unification and Quantum Gravity

There are approaches to unification and quantum gravity that are more foundational. Several of them are characterized by a property we call background independence. This means that the geometry of space is contingent and dynamical; it provides no fixed background against which the laws of nature can be defined. General relativity is background-independent, but standard formulations of quantum theory—especially as applied to elementary particle physics—cannot be defined without the specification of a fixed background. For this reason, elementary particle physics has difficulty incorporating general relativity.

String theory grew out of elementary particle physics and, at least so far, has only been successfully defined on fixed backgrounds. Thus, the infinity of string theories which are known are each associated with a single space-time background.

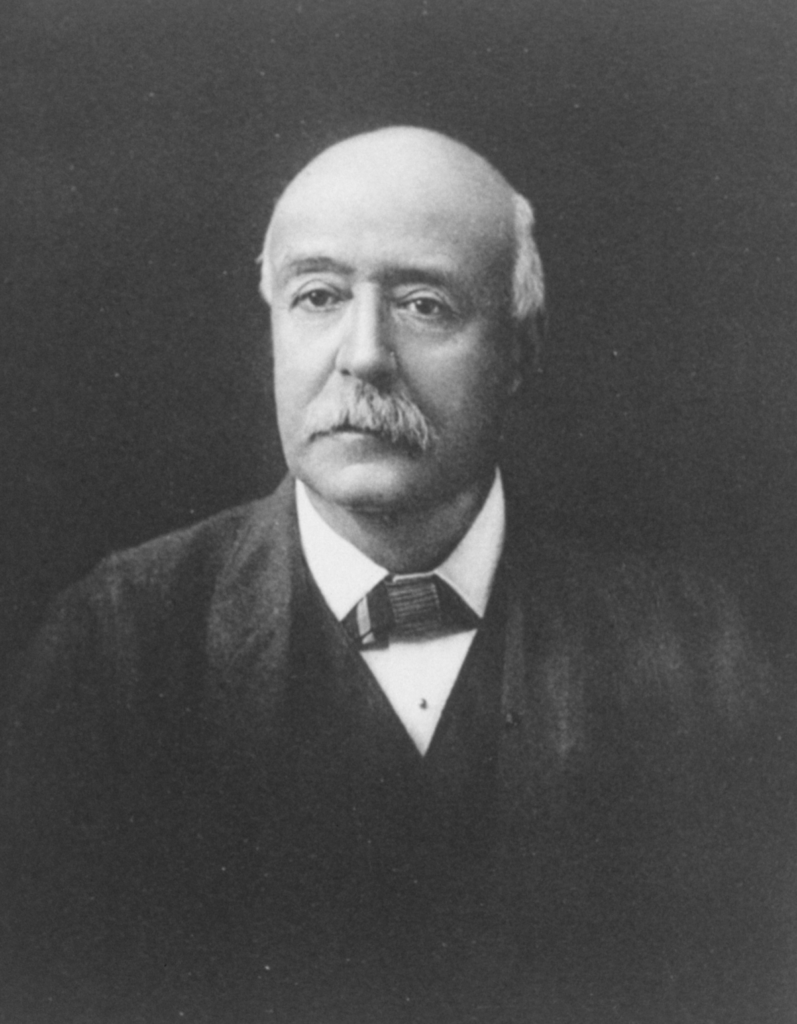

Those theorists who feel that theories should be background-independent tend to be more philosophical, more in the tradition of Einstein. The pursuit of background-independent approaches to quantum gravity has been pursued by such philosophically sophisticated scientists as John Baez, Chris Isham, Fotini Markopoulou, Carlo Rovelli, and Raphael Sorkin, who are sometimes even invited to speak at philosophy conferences. This is not surprising, because the debate between those who think space has a fixed structure and those who think of it as a network of dynamical relationships goes back to the disputes between Newton and his contemporary, the philosopher Leibniz.

Meanwhile, many of those who continue to reject Einstein’s legacy and work with background-dependent theories are particle physicists who are carrying on the pragmatic, “shut-up-and calculate” legacy in which they were trained. If they hesitate to embrace the lesson of general relativity that space and time are dynamical, it may be because this is a shift that requires some amount of critical reflection in a more philosophical mode.

A Return to the Old Style of Research

Thus, I suspect that the crisis is a result of having ignored foundational issues. If this is true, the problems of quantum gravity and unification can only be solved by returning to the older style of research.

How well could this be expected to turn out? For the last 20 years or so, there has been a small resurgence of the foundational style of research. It has taken place mainly outside the United States, but it is beginning to flourish in a few centers in Europe, Canada, and elsewhere. This style has led to very impressive advances, such as the invention of the idea of the quantum computer. While this was suggested earlier by Feynman, the key step that catalyzed the field was made by David Deutsch, a very independent, foundational thinker living in Oxford.

For the last few years, experimental work on the foundations of quantum theory has been moving faster than experimental particle physics. And some leading experimentalists in this area, such as Anton Zeilinger, in Vienna, talk and write about their experimental programs in the context of the philosophical problems that motivate them.

Currently, there is a lot of optimism and excitement among the quantum gravity community about approaches that embrace the principle of background independence. One reason is that we have realized that some current experiments do test aspects of quantum gravity; some theories are already ruled out and others are to be tested by results expected soon.

Collective Phenomena

A notable feature of the background independent approaches to quantum gravity is that they suggest that particle physics, and even space-time itself, emerge as collective phenomena. This implies a reversal of the hierarchical way of looking at science, in which particle physics is the most “fundamental” and mechanisms by which complex and collective behavior emerge are less fundamental.

So, while the new foundational approaches are still pursued by a minority of theorists, the promise is quite substantial. We have in front of us two competing styles of research. One, which 30 years ago was the way to succeed, now finds itself in a crisis because it makes no experimental predictions, while another is developing healthily, and is producing experimentally testable hypotheses. If history and common sense are any guide, we should expect that science will progress faster if we invest more in research that keeps contact with experiment than in a style of research that seeks to amend the methodology of science to excuse the fact that it cannot make testable predictions about nature.

Also read: What Physics Tells Us About the World

References

1 Smolin, L. 1997. The Life of the Cosmos. Oxford University Press.

2 Weinberg, S. 2005. Living in the multiverse.

Further Reading

Smolin, L. 2006. The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next. Houghton Mifflin, New York.

Woit, P. 2006. Not Even Wrong: The Failure of String Theory and the Search for Unity in Physical Law. Basic Books, New York.

About the Author

Lee Smolin is a theoretical physicist who has made important contributions to the search for quantum theory of gravity. He is a founding researcher at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ontario. He is the author of Life of the Cosmos (Oxford, 1997), Three Roads to Quantum Gravity (Orion, 2001), and the forthcoming, The Trouble with Physics (Houghton Mifflin, 2006).