To accommodate a growing world population, while conserving resources and providing for quality of life, cities must find sustainable ways to continue providing clean water, transportation, energy, and waste disposal.

Published March 8, 2010

By Catherine Zandonella

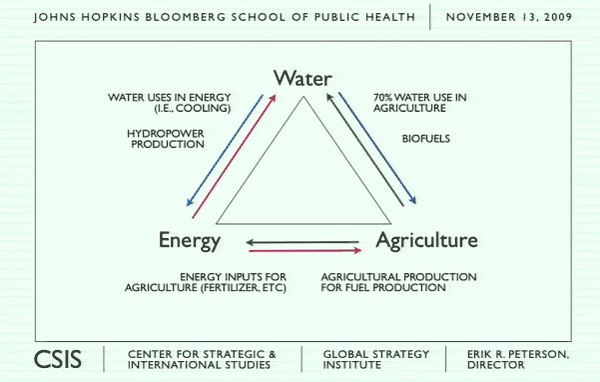

More than three billion people live in cities worldwide, and experts predict that number could grow to five billion by 2025. One billion of those urban dwellers lack basic services and infrastructure. Today’s cities consume almost 70% of global energy resources and, in turn, generate 70% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. To accommodate a growing world population, while conserving resources and providing for quality of life, cities must find sustainable ways to continue providing clean water, transportation, energy, and waste disposal.

Converting today’s cities into sustainable environments, however, will require large capital investments. The retrofit of existing building stock in the United States alone is estimated to cost $1 to $2 trillion. Although governments have increased their financial commitments to sustainable infrastructure, private sector investors must become involved to provide the level of funds that are needed. “We have to get better at the financing game,” said Gordon Feller of the Urban Age Institute.

Many Questions Remain

Financing is an integral part of a solution, but many questions remain. On the path toward sustainable urban development, how are businesses and NGOs partnering with governments to accelerate the adoption of new policies and new technologies—while making cities the living lab for that process? How can leaders from the public and private and independent sectors work together to finance cleaner and greener urban initiatives that will smarten the city’s infrastructure and transform the built environment?

To discuss these questions and chart a path forward, as well as to learn about novel financing mechanisms from leaders who are already implementing these methods, key stakeholders in urban planning met at The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy) on January 7, 2010, for a conference on sustainable city financing presented by the Urban Age Institute and the Academy. The day-long conference was sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Standard & Poor’s/McGraw-Hill, Meeting of the Minds, U.S. Conference of Mayors, and others.

Financial Benefits of Sustainable Cities

Where once development agencies thought it necessary to discourage urban migration, today they recognize that urbanization is essential to the economic vibrancy of a region. “It is a paradigm shift,” said World Bank Group’s Abha Joshi-Ghani, “from urbanization being bad in terms of grime, crime, and congestion, to being the key driver of economic growth and the key aspect of bringing down poverty.”

For this development to proceed, however, the environment cannot be an afterthought. Regional planning is essential. Policy leaders must change how businesses value the environment to attract investors to finance the transition to sustainability. “We have to change from regarding the environment as a cost center to thinking of it as a profit center,” said Albert F. Appleton, former chief of the NYC Department of Environmental Protection.

Show, Don’t Tell

When for-profit companies can be shown the value of a retrofit to their bottom line, they will be inclined to make investments. The evolution of the nationwide garbage disposal company Waste Management, Inc., is a good example. In response to shrinking revenue from their landfills, the company branched into services that help cities reduce waste, recycle, and convert waste into energy, said Waste Management’s Barry Caldwell. The key is to demonstrate the financial benefits of sustainability. “We’ve found that one of the key words that changes the template is ‘money,'” said artist and designer Michael Singer of Michael Singer Studio.

This holds true for government as well. For example, the projected cost of accommodating new residents was the driver behind NYC’s sustainable development plan, or PlaNYC, said Rohit T. Aggarwala of the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability. Through conservation, the city can avoid building new power plants. “We realize that sustainability is not a luxury item,” he said.

To show investors benefits, however, metrics are needed that can quantitatively demonstrate the savings from energy efficiency and other retrofits. E. Sarah Slaughter of the MIT Sloan School of Management said students there are working to develop these metrics.

Aligning Incentives: Attracting Investors to Sustainable City Financing

Demonstrating the benefits of sustainable investments is essential to attracting financing. However sometimes these benefits are misaligned so that the entity making the investment is not the entity that enjoys the benefits. For example, when a utility company installs filters on its smokestacks to cut emissions, rates of respiratory illnesses in the community tend to decline but the utility itself does not realize the benefit. When a homeowner pays for energy-efficient retrofits but later relocates, the benefits go to the new owner of the home.

One mechanism for aligning incentives is the property assessed clean energy (PACE) bond. Jack D. Hidary of SmartTransportation.org explained how these work: The city issues a bond that establishes funds that city residents and property owners can borrow for energy retrofits. The loan is then paid back as a surcharge on the home’s property tax. This is different from other home-retrofit loans, where the loan obligation stays with the borrower even after selling the home. Property taxes have a near zero default rate, so the risk to investors is small.

Climate Change as a Motivation for Sustainable Urbanization

As world governments stall on agreeing to a comprehensive greenhouse gas reduction policy, city and state governments are stepping up to cut emissions on their own. But smaller governments do not have the funds that will be required for such an effort, and they must turn to the private sector. “Finance and investment is a very important part of the formula in terms of climate change and clean energy,” said Vickie A. Tillman of The McGraw Hill Companies, Inc., a leader in information and financial services.

Over the past five years, a number of local government and building codes have driven the trend in green construction. The stimulus bill provides a focus on renovation and renewable energy, while tax breaks provide incentive for residential energy efficiency, said Harvey Bernstein of McGraw-Hill Construction. These government incentives could be leveraged to attract even more investment from the private sector.

While the benefits of environmental investments should reside with the investor, a financial opportunity also arises when the costs reside with the polluter. Carbon cap-and-trade systems, already in place in Europe, are one incentive for greenhouse gas-emitting industries to reduce their emissions. Carbon markets have the potential to become significant investment vehicles if private investors see them as good investments, said speakers from the finance-information company, Standard and Poor’s, a McGraw-Hill company.

Carbon-offset Projects

Many private sector investors are wary of carbon markets because the technological feasibility of reducing emissions and the ease of passing costs to consumers vary by industry, said Michael Wilkins of Standard and Poor’s Rating Services. Few regulatory bodies exist to validate carbon-offset projects. Additionally, environmental regulations present a challenge to credit quality because they put restrictions on how companies do business. Government policy makers must resolve these issues so that controlling carbon dioxide emissions can serve a role in driving the energy-efficient retrofitting of cities.

A number of federal loan programs aimed at stimulating the development of green technology companies are available in the U.S, said Standard and Poor’s’ Steven Dreyer, but many of these projects are highly leveraged and thus present a risk to investors. Incentives for green building can be found in every state, many cities, and at the federal level through tax incentives and subsidies, added Peter V. Murphy of Standard and Poor’s Rating Services. However government spending might be used more effectively if government funds are leveraged to attract investments from the private sector.

Financing the Sustainable City

Overcoming the barriers that have kept private investors from funding sustainable development is one of the keys to moving forward, said Eduardo Rojas of the Inter-American Development Bank. Private investors are more likely to invest in a sustainable public-sector project if the project has a sound structure including clearly defined responsibilities among levels of government and fiscal discipline; citizen representation and oversight; organizational structure, administrative systems, and human resource policies; and adequate public-sector funding from taxes or fees.

A number of mechanisms have already proven successful. One such mechanism is to enlist the human and financial resources already in the community. Brian English of CHF International discussed a program in India that helped slum residents set up a garbage-removal program whereby residents each pay a small fee. Somsook Boonyabancha of the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights in Thailand described how community members pool their money together into a savings account that can be used to invest in community improvements.

Public-private partnerships are attractive mechanisms for allaying fears about the risk of a development project. Pegeen Hanrahan, Mayor of Gainesville, Florida, has established the nation’s first solar feed-in tariff (FIT) project, where the city pays solar energy providers for feeding electricity into the grid. The project has spurred the creation of new solar energy companies.

Sustainable Development in the Developing World

Private sector and global organizations can come together to create new sustainable development in the developing world. Private capital is often reluctant to invest in early phases of urban revitalization because of the uncertainties involved, so public entities are better placed to identify projects, lease or purchase the land, obtain all the relevant permissions and permits, and provide technical support. An example of this approach is the Estruturadora Brasileira de Projetos, S.A.-EBP, a public entity that identifies, develops, and obtains regulatory approval for sustainable development projects and has private companies bid to build the projects, said Helcio Tokeshi of the EBP.

In addition to motivating investors to invest in sustainable development, it is important to find ways to motivate consumers to save energy. Financial mechanisms such as higher fees for garbage disposal and electricity service are potent motivators, but not all human motivations are financial. Competitions between apartments, floors in an office building, and even cities can spur the naturally competitive human spirit, said Jonathan F. P. Rose of Jonathan Rose Companies, which specializes in green real estate policy, planning, development, and investment.

A number of innovative projects have sprung forth from companies led by forward-looking executives, said Peter Miscovich, an executive of the global advisory and management company Jones Lang LaSalle. These innovations are demonstrating that it is possible to break through the logjams that have impeded sustainable development projects.

Sustainable, Livable, and Economically Vibrant Urban Centers

Although some financial mechanisms are available to fund the retrofit and building of sustainable cities, clearly more innovation is needed. “We need mechanisms for financing an urban future,” said Nicholas You, a senior advisor to the executive director of UN-HABITAT. “Here we have a bridge that needs to be built.”

A crucial step in building that bridge is to gather information about the most pressing challenges facing cities, as well as to understand the value that urban inhabitants place on the sustainable provision of energy, water, transportation, and other vital city services. The new Gallup Institute for Global Cities is collecting this information, said Ian Brown of Gallup. IGC is launching several major research initiatives in coming months, in partnership with Urban Age Institute, and is actively looking for insights from conference sponsors and participants.

To work toward developing novel financing strategies, cities must become connected, not just through the Internet but through person-to-person communication, said Tim Campbell of the Urban Age Institute. Research shows that a high volume of exchange is already underway on a global scale and that innovative cities depend on a trusting climate in networks of city leadership. With that trust, city leaders will be able to convert new knowledge to innovation and attract the novel financing mechanisms and technologies they need to develop sustainable, livable, and economically vibrant urban centers.