A look at the history and future of two groundbreaking bastions of knowledge dissemination.

Published August 1, 2014

By Gina Masullo

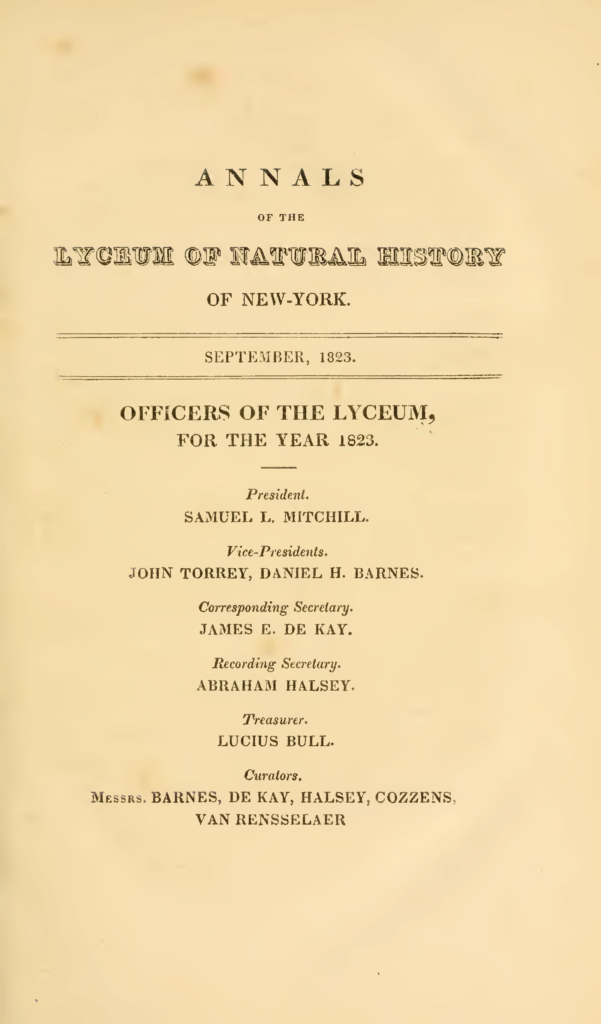

In an industry with more than 28,000 academic journals, to say that interested audiences have abundant choices for how they consume scientific information would be a gross understatement. But that wasn’t always the case. When the first issue of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (Annals) was published in 1823, it was one of only a handful of scientific journals, most of them unsuccessful, and it had around 100 subscribers—a number that remained stagnant for several years.

Though the interdisciplinary peer-review journal had an inauspicious start, its debut publication sparked a rich tradition of excellence and innovation in scientific publishing. Annals evolved from a resource for local scientific elites into a much respected and cited journal that’s read the world over, one of the longest continuously published scientific serials in the United States and a powerful symbol of the democratization of cutting-edge scientific information. Today, the Academy’s flagship publication, Annals has published more than 1,300 volumes over 191 years.

As the Academy began researching a variety of topics in greater detail during its first decades, its popularity grew; and, by association, so did interest in Annals. Sales of the journal quadrupled in 1939, the same year Eunice Miner was appointed executive secretary of the Academy. Miner passionately expanded the number of Academy memberships and hosted events; accordingly, Annals’ distribution increased exponentially.

By the 1960s, the Academy was sponsoring several dozen conferences a year, and distributing Annals to an audience of about 40,000. Each issue informed readers about the Academy’s conference proceedings, on topics increasingly varied and newsworthy—and a look back through its pages is a window into the challenges the scientific community has faced and overcome throughout history.

The First Large Scientific Assembly on Antibiotics

In 1946, for instance, the Academy hosted the first large scientific assembly on antibiotics, with a particular focus on combating tuberculosis. Margaret Mead published several Annals papers during her time as vice president at The New York Academy of Sciences in the 1970s; other notable contributors over the years have included Paul Ekman, Franz Boas, Edmund B. Wilson, Joshua Lederberg, and Ralph Steinman.

The Academy’s Puerto Rico survey, initiated in the early 20th century, attracted perhaps the most attention of all. Co-founder of the New York Botanical Garden (and Academy member) Nathaniel Lord Britton initiated a four-year study of the island’s geology, botany, and zoology. Starting in 1914 and including research from scientists in various sectors, the survey was the first and most comprehensive of its kind.

Reports from the island, published in Annals as well as the Journal of the New York Botanical Garden and the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, were so well received that the project quickly grew in size, scope, and financial backing. By the summer of 1916, 23 research groups had visited the island to examine areas including entomology, mycology, anthropology, and paleontology. The groundbreaking project ultimately expanded to the Virgin Islands, incorporated research from an international community of scientists, and lasted more than 25 years, culminating in the publication of the multi-volume Scientific Survey of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Expanding Scope & Reach

Annals has documented a large proportion of the conferences held by The New York Academy of Sciences, and, since 1981, it has covered news and discoveries from unaffiliated scientific conferences as well. With the expansion of technology and excitement for attention-grabbing efforts such as space exploration, interest in the Academy and its flagship publication continued to grow.

So, too, did the journal’s scope and reach. Annals is now available in 4,505 institutions worldwide via a partnership with the Wiley Online Library of licensed subscriptions, and in thousands of institutions in the developing world via philanthropic initiatives. During the last year (June 2013 – June 2014), Annals was the fifth-most accessed journal among Wiley’s 2,304 journals, where it received 2,283,137 visits. Google Scholar ranks the journal number 10 on its list of top health and medical science publications, in the company of esteemed publications like The New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet.

Douglas Braaten, PhD, editor-in-chief of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences and executive director of science publications, explains the journal’s continued relevance this way: “One of the most unique things about Annals is the ability to produce individually themed issues. We can essentially design what we publish; currently, that’s 28 individual projects per year, on varying topics—so readers really get both scope and depth into the topics.

“We also produce volumes stemming from conferences, which is one of the reasons Annals continues to be unique; we will commission papers from the invited speakers in a field from an international conference. The resulting collection of papers provides a state-of-the-art view of a topic for people who weren’t in the room. We have over a 100-year history of providing conference proceedings, the aim of which is to democratize scientific information.”

A Stellar Reputation

Also important to the publication’s stellar reputation is “a high-quality, peer-review process” and “traditional journal standards and ethics.”

Alongside its stalwart ethics, the Academy’s commitment to innovation ensures Annals’ growing influence and credibility. Within the last decade, annual reviews of specific scientific topics have become a staple of the publication.

George Uhl, PhD, chief of the Molecular Neurobiology Research Branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, serves as editor of the Annals series Addiction Reviews. “I don’t think there is anything like it in addiction, and I serve on several publication committees in this area,” he says. “The effort with Addiction Reviews is to try to review things that are getting to the point of being interesting rather than things that are already acknowledged by everyone as interesting, and I think that has helped the impact factor”—a statistic that calculates the average number of outside citations per article—which for this series is an impressive 13, compared to similar publications’ typical scores of two or three.

Other annual review topics include The Year in Cognitive Neuroscience, edited by Michael Miller, PhD, professor and vice chair of psychological and brain sciences at UC Santa Barbara, and Alan Kingstone, PhD, distinguished university scholar and professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia.

“Starting up an annual review in cognitive neuroscience was such an obviously brilliant idea,” explains Kingstone. “The field was nearly 20 years old, and there was a real need to provide those in cognitive neuroscience with a place to pull together key ideas on an annual basis.”

The Value of Themed Volumes

He continues, “The value of the themed volumes is evident in the impact that it has had on the field since its initial publication in 2008. As of last year, the reviews contributed to The Year in Cognitive Neuroscience have averaged 38 citations. The very first article in the 2008 edition, “The brain’s default network,” has been cited over 2,500 times. This impact rivals some of the most highly regarded journals, and demonstrates the high value the field places on these review articles to keep researchers up to date on a quickly evolving field.”

The Academy remains committed to quality of research, as well as innovation in information delivery. The number of methods the Academy uses to communicate research and ideas to the scientific community and beyond continues to grow. The 191 year-old journal has evolved from a print-only publication to a robust collection of interactive multimedia tools. Thanks to its partnership with Wiley, Academy members and institutions with Annals benefits can access every volume ever published via the Academy website; they can even read archives via a free mobile app.

eBriefings: Multimedia Science Reports

Further illustrating its commitment to bringing comprehensive, cutting-edge scientific information to a truly global audience, in 2003 the Academy introduced eBriefings: interactive, userfriendly web resources that increase the longevity and impact of Academy events. Conceived in the wake of the Academy’s interdisciplinary SARS conference, eBriefings are now a standard offering, providing the benefits of Academy events and conferences to those who are unable to attend in person.

The multimedia presentations include meeting summaries written by science writers and scientists, a selection of speakers’ slides and audio, and links to related information. Over the last decade, eBriefings have been cited by news outlets including The Wall Street Journal, US News & World Report, and Med News Today. They receive around 10,000 unique page views each month; in the last fiscal year, the presentations were accessed from more than 140 countries.

Explains Brooke Grindlinger, PhD, executive director of scientific programs at the Academy: “eBriefings offer everyone within the global scientific community access to today’s cutting-edge knowledge conveyed by world-renowned leaders in almost every discipline in science and technology. It’s your science, on your schedule, sowing the seeds for your next big idea.”

The Academy produces approximately 60 eBriefings each year; recent topics have run the gamut from Alzheimer’s disease to the use of “big data.” The online resources are presented in partnership with a global network of partners, including The Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise, The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, The National Institutes of Health, and The U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Expanding Interest in Emerging Topics

Jeanne Garbarino, PhD, director of science outreach at Rockefeller University, led an Academy panel in September 2013 titled “Crowdfunding: An Emerging Funding Mechanism for Science Research.” She explains that the eBriefing helped expand interest and research in this emerging topic: “It allowed me to connect with others who are interested in this topic, and also provided an opportunity to discuss more ways in which crowdfunding could be applied to scientific research.”

Garbarino adds, “Given the disproportionate distribution of scientific and educational resources in our nation, providing free access to high quality materials is always a good thing.”

This egalitarian approach to the dissemination of scientific knowledge is quite fitting in the context of the Academy’s history. As early as 1903, audiences filled the lecture hall at the American Museum of Natural History to hear Academy presentations on topics such as the Mount Pelée volcano on Martinique or the physical and economic aspects of Mexico. These presentations were particularly appealing because they incorporated cutting-edge technology of the time—lantern slides and stereopticon—that helped bring scientists’ invaluable research to life.

Hints Braaten, the editor of Annals: “A new contract with Wiley is reinvigorating Academy publishing and opening new avenues, such as Academy book publishing.” And as the technology and science fields continue to evolve, you can be sure that the Academy’s approach to disseminating vital information will, too, ensure that scientists and non-scientists alike will have access to globe-changing ideas and evidence for generations to come.

About the Author

Gina Masullo is a journalist in New York City.