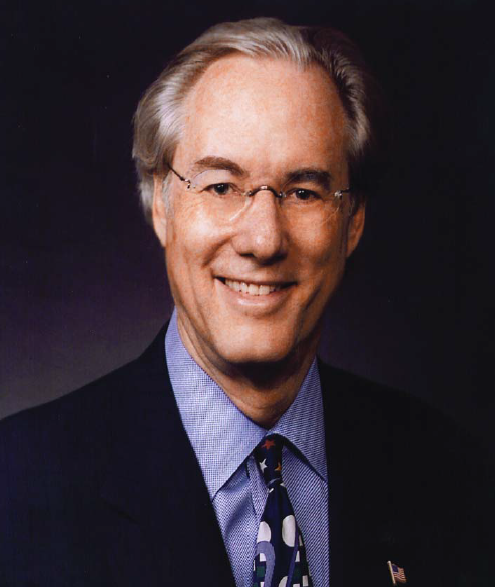

Inspired by his mother-in-law’s courageous, but heartbreaking battle, George Vradenburg has teamed up with the Academy to take on Alzheimer’s disease.

Published August 1, 2013

By Noah Rosenberg

George Vradenburg’s resume reads like a roadmap to prototypical business success. He was Phi Beta Kappa in college and attended Harvard Law School. He later co-published a magazine and brokered deals for media giants like CBS, Fox, and AOL, founding two charities in his spare time. George Vradenburg, to be sure, is a man who seized his life and career by the horns.

But then it all changed. In the early ’90s, as his mother-in-law faded with Alzheimer’s disease, Vradenburg could only sit back idly, helplessly. “I saw the progress from paranoia to hallucinations to falls to institutionalization to the late stage where she was physically immobile and totally unaware of her surroundings and her family,” Vradenburg remembers. “It is not a long goodbye, not the romanticized long farewell. It is a horrid disease.”

Of course, Vradenburg and his family weren’t alone. Today, 36 million people struggle with the disease worldwide, and that number is expected to grow to 115 million by 2050. So Vradenburg was shocked to realize that Alzheimer’s research and treatment had long been stagnant, frozen in a frustrating holding pattern.

True to form, Vradenburg decided he needed to do something about it. He enlisted his screenwriter wife to develop plays about her mother’s battle with Alzheimer’s, but it didn’t take Vradenburg long to understand that the level of zeal he brought to bear on curbing the disease was practically unparalleled.

“I thought, ‘Why in the heck is there not a national strategic plan on this?’” Vradenburg recalls, still incredulous. “I was frustrated by the absence of urgency and passion. Everyone seemed to be conducting business as usual.”

Taking Action

Vradenburg set out to change the nature of the game. He partnered with the Alzheimer’s Association and, for eight years, put on an Alzheimer’s fundraising gala. From there, he formed a political action committee, an Alzheimer’s study group, and, in 2010, co-founded USAgainstAlzheimer’s, an education and advocacy campaign for which he still serves as chairman.

And now, nearly two decades after his mother-in-law’s death, Vradenburg’s Global CEO Initiative—a newly-formed private-sector committee designed to collaborate with the public sector, non-profit community, and academia—has joined forces with The New York Academy of Sciences in a next-generation, cross-industry collaboration, called the Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia Initiative (ADDI), that will attempt to effectively combat the disease once and for all.

The CEO Initiative’s goals, after all, are directly aligned with the Academy’s own efforts. Launched in 2011, the aim of the ADDI is the translation of basic research about disease mechanisms into the development of new methods for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. The Academy developed a Leadership Council of multi-sector stakeholders—academic researchers, industry scientists, patient advocates, and government and foundation representatives—to define priorities and develop action steps for progress in Alzheimer’s diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.

Creating an Agenda

The Holy Grail for the ADDI is the development and implementation of a comprehensive research agenda aimed at preventing and treating Alzheimer’s by 2025. It is a bold, ambitious, and lofty goal—Vradenburg is the first to admit that.

But, he says, “I can’t be giving up. You have to continue to push ahead no matter how many failures there are.”

And so Vradenburg decided to support the ADDI and, in turn, the many multi-sector experts comprising the collaborative working group that dedicates its time and expertise to define key action items around big challenges: gaining a better understanding of the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s; developing innovative therapeutic approaches and strategies to engage patients in clinical trials; decreasing the time, cost, and risk of drug development; and increasing funding models, such as public-private co-investment, social impact investment, and new public funding mechanisms.

The CEO Initiative generously seeded its partnership with the Academy with a contribution of $325,000. Academy President and CEO Ellis Rubinstein considers the gift “a testament to the power of the partnerships being facilitated by The New York Academy of Sciences.”

“George is a visionary who realizes that the complexity of the grand challenges confronting humanity can only be addressed efficiently through alliance-building,” Rubinstein says. “For this reason, we at the Academy regard George as a role model for budding philanthropists: he uses his resources not for self-aggrandizement but to catalyze collective action.”

The Path to 2025

The joint research agenda, to be developed by the Academy and the CEO Initiative by late summer 2013, is simply the beginning. The working group’s results will feed into the Academy’s upcoming conference, “Alzheimer’s Disease Summit: The Path to 2025,” to be held on November 6 and 7 at its Lower Manhattan headquarters.

The gathering will build on the work of the National Institutes of Health’s biennial Alzheimer’s Disease Research Summit and, according to the Academy, “advance a research agenda that is informed by the needs, experience, perspectives, and lessons learned from industry, academic, and government research efforts.”

Following the November summit, the working group will produce a meta-analysis, including long-term plans for patient engagement in clinical trials, preventative measures, and future coordination efforts.

Not one to chase progress timidly, Vradenburg cautions that the Academy and the CEO Initiative must use the fall Alzheimer’s Summit “not as a conversation but actually an action-driver. We need to use it as a deadline for taking certain steps.” To that end, he explains that the working group is expecting to reveal breakthroughs in the area of biomarkers, data-sharing, clinical trial recruitment, and innovative financing mechanisms during the summit.

Synergies Across Organizations

Vradenburg sees his partnership with the Academy as the logical path forward between two organizations whose objectives, and even personnel, have overlapped in the past.

“What intrigued me about the Academy was their reach—into academia and geographically,” he says, commending the Academy’s visionary leadership. “They have a reputation for taking on challenging issues. They have the same spirit of innovation and drive that I think I have, so there’s been sort of a mind meld at the leadership level.”

The feeling is mutual. “George brings an incredible energy to all of his endeavors,” says Academy Executive Vice President and COO Michael Goldrich, “which, combined with his formidable business acumen, makes him a person who gets results.”

A Critical Time

On top of that, the ADDI is embarking at perhaps the optimal time in the war against Alzheimer’s. This year, for instance, President Obama mentioned the importance of Alzheimer’s research in his State of the Union address—a sign of what Vradenburg calls a “significant uptick” in government attention to the disease. As a result, there has been “enormous progress” in research, he says, notably in the area of enhanced imaging techniques that allow for the detection of the disease up to 20 years before symptoms appear.

Progress, however, has been largely one-sided. “On the treatment side,” Vradenburg laments, “there have been zero advances.” This leads to a cruel reality in which patients might learn of their fate decades before it sets in, and with no way to prevent the disease’s onset.

“It’s frustrating for the patient population out there,” Vradenburg stresses. “They get treated with the wrong drugs; they’re wrongly diagnosed and mistreated at earlier stages.”

“And there’s also the second-hand victims, the caregivers,” he adds. “People are going bankrupt or having to quit work or delay college to care for their loved ones. There’s an emotional, physical, health, and financial impact of this disease on families around the world today.”

Exceeds $600 Billion Worldwide

In fact, the annual burden of caring for the current number of Alzheimer’s patients and those with related dementia exceeds $600 billion worldwide and will only continue to grow in the absence of meaningful innovation.

Vradenburg is aware, though, that success doesn’t come easy. He explains that the ADDI is pushing to introduce first-generation disease-modifying treatment into the marketplace by 2020 and to foster a means of prevention and effective treatment in the marketplace by 2025, as well as to develop the critical intervention methods to get treatment into the hands of at-risk populations.

“All of my efforts,” he emphasizes, “have basically challenged people to identify the critical hurdles that would change the trajectory and speed, the velocity and volume of what we’re doing. I’ve always got to be optimistic,” Vradenburg says.

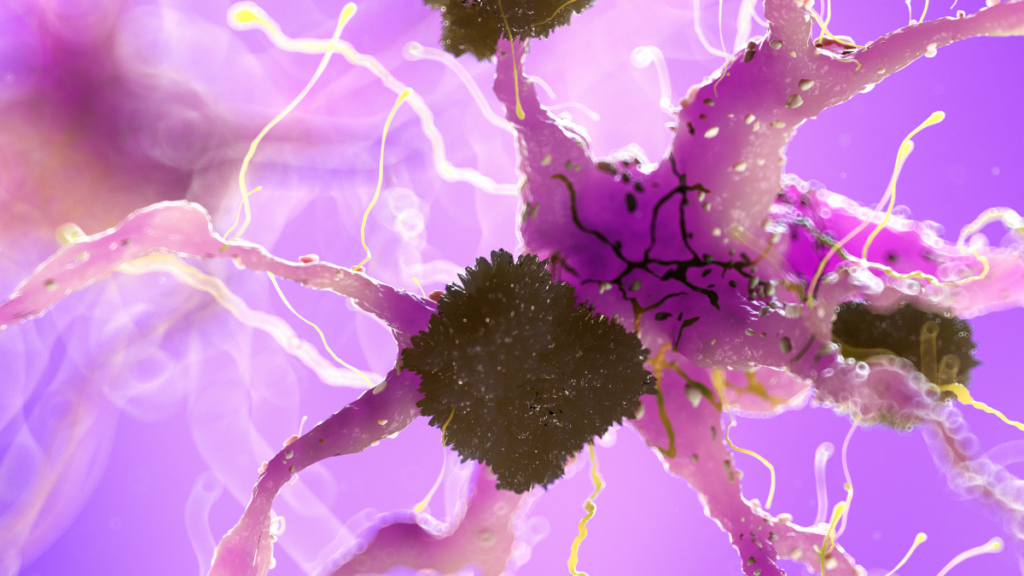

Also read: Resolving Neuro-Inflammation to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease and Pain

About the Author

Noah Rosenberg is a freelance journalist in New York City.