Mental illnesses present a major health, social, and economic burden and affected individuals experience disproportionately higher rates of both disability and mortality. In fact, the CDC reports that nearly 50% of U.S. adults will experience a mental illness at some point in their lifetime. And according to the WHO, depression alone accounts for 4.3% of the total disease burden worldwide and is the single greatest cause of disability. Yet despite enormous unmet need, efforts to develop new therapies for mental illness have stalled in part because of a need for more clarity surrounding the biological underpinnings of these diseases. On October 9, 2018, the New York Academy of Sciences presented Advances in the Neurobiology of Mental Illness. The one-day symposium, sponsored by Janssen Research & Development, LLC, brought together scientists, clinicians, and policymakers to discuss the genetics, molecular biology, and neurobiology of a wide range of mental illnesses. Topics included novel targets for treating depression, using genetic profiles to assess the risk of experiencing mental illness, and broader questions about battling the stigma surrounding such conditions.

Speakers

Hilary Blumberg, MD

Yale School of Medicine

David Bredt, MD, PhD

Janssen Neuroscience

Wayne Drevets, MD

Janssen Research & Development, LLC

Steve Hyman, MD

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

Jeff Lieberman, MD

Columbia University

Eric Nestler, MD, PhD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Maria Oquendo, MD, PhD

Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH

University of California, San Diego

Event Sponsor

The Molecular Basis of Mental Disorders

Speakers

Hilary Blumberg, MD

Yale School of Medicine

Steve Hyman, MD

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

Eric Nestler, MD, PhD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Highlights

- Early-life experience changes response to stress into adulthood by affecting the expression of key genes

- In people with bipolar disorder, brain structure and activity change during adolescence and early adulthood.

- Polygenic risk scores are a promising tool for gauging a person’s likelihood of developing a psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia.

Transcriptional and Epigenetic Mechanisms of Depression

Techniques measuring how genes are transcribed — in animal models and human post-mortem tissue — are providing new and valuable insight into depression, and potentially, new therapies, said Eric Nestler of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. His team uses such techniques to explore the idea that behavioral experience, such as early life stress, can produce permanent changes in the genome structure and gene expression of brain cells; these permanent changes in turn contribute to shifts in behavior for a lifetime and predispose a person towards susceptibility to stress.

In 2016, Nestler and his colleagues subjected mice to a form of chronic stress and conducted RNA sequencing in four different brain regions. The stress made about half the mice susceptible to developing behaviors associated with depression and anxiety, while the other half remained resilient to mental health effects. The resilient animals tended to have bigger changes in gene expression, suggesting that susceptibility may be caused by the brain’s inability to make the needed changes.

The researchers then conducted a similar gene expression study on post-mortem tissue of people who had depression. They found a surprising result: Gene expression changes observed in women overlapped very little with those seen in men, suggesting that the biological underpinnings of depression differ in men and women. Animal models showed the same sex difference. “That really argues for drug discovery processes that will look at both sexes independently,” Nestler said. What’s more, three different types of chronic stress dysregulated different sets of genes, with little overlap between them.

Early life stress is one of the strongest biological risk factors for depression. Most people can withstand that stress and develop normally into adulthood, but they retain an increased vulnerability to later stress. To understand the molecular mechanisms involved, Nestler’s team investigated how early life stress affects gene expression in mice. Most studies deliver early life stress continually over the first three weeks of life, but in this case, the researchers delivered early life stress over two time periods. Animals stressed during the second period, but not the first, show abnormal social behavior when stressed later in life. Gene expression studies in three different areas of the brain suggest that stress during the second early life period changes gene expression to look as though the animal has experienced chronic stress in adulthood — again, with the changing genes being different in males and females.

This pattern was strongest in one of the brain regions studied, called the ventral tegmental area (VTA), in male mice. The largest portion of those gene expression changes were regulated by a gene called Otx2. When they overexpressed that gene in the VTA of young male mice after the mice had experienced stress during the second early life period, the animals were protected from stress in adulthood. In turn, impairing Otx2 expression during that time increases stress susceptibility and dysregulates the stress-related genes irreversibly.

Otx2 is probably just one of several genes regulating susceptibility to stress, but it provides a model for how early life experience can alter stress response for a lifetime. The researchers are now studying what Nestler calls “chromatin scars” — chemical markers in the dysregulated genes.

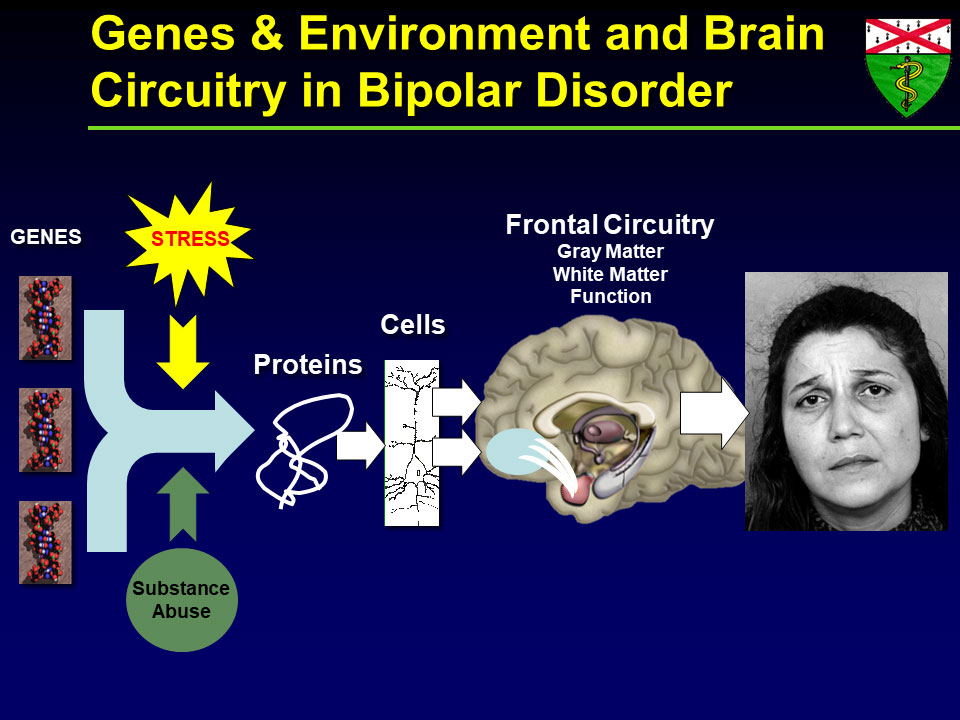

The Brain in Bipolar Disorder

Elevated mood episodes are considered a hallmark of bipolar disorder, and these symptoms generally emerge during adolescence. But the condition is also characterized by more primitive and less widely-studied symptoms such as changes in sleep, circadian rhythms, and energy levels, said Hilary Blumberg of the Yale School of Medicine.

These features may emerge earlier than emotional disturbances, and researchers are beginning to look closely at how such symptoms might be therapeutically targeted. Early intervention could prevent the progression of bipolar disorder, said Blumberg — this is especially crucial because about 50% of people with bipolar disorder attempt suicide, and 15%–20% die by suicide.

Most research on bipolar disorder has focused on the circuitry of emotional regulation. Blumberg described two key components of this circuitry: The amygdala, an almond-shaped region deep in the brain that gets excessively activated in people with bipolar disorder; and the ventral prefrontal cortex, the frontal part of the most recently-evolved part of the brain, the cerebral cortex, where activation can be lower in people with bipolar disorder. These regions are highly interconnected.

Blumberg’s lab hypothesized that by adolescence, functional and structural changes might be detectable in the amygdala, which matures earlier. The frontal cortex develops later, so the researchers predicted that its structure and function would progressively diverge from normal during adolescence and young adulthood. Blumberg and her team conducted three types of brain scanning to image the structure and function of the two brain regions, as well as the connection between them, and observed these changes. They also found that differences in a specific part of the frontal cortex correlate with attempts to commit suicide, regardless of whether subjects were diagnosed with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder.

Additionally, Blumberg and colleagues are investigating adults with bipolar disorder to better understand how the aging process interacts with psychiatric conditions. Older adults often have a higher suicide risk; little research has focused on this developmental stage, but there is evidence that lithium may be effective in reducing suicide risk. They are also using brain imaging to explore the effects of genes thought to play a role in bipolar disorder, and identifying the effects of early life stressors, such as physical or emotional abuse or neglect, on brain structure and function in adolescence.

The group developed a behavioral therapy called BE-SMART that focuses on helping people with bipolar disorder improve their emotional regulation, and regularize their sleep and daily rhythms. Preliminary imaging studies show that after undergoing the therapy, patients have less activation in their amygdala and more in their frontal cortex. “In addition to pharmacological treatments, there are many other strategies that may help improve brain circuitry trajectories,” Blumberg said.

A New Molecular Map for Mental Disorders

In the 1960s, geneticists realized that psychiatric disorders were complex, but early researchers estimated that some 20 genes might underlie these conditions. Today, researchers are realizing that many thousands of variants in many hundreds of genes are involved, said Steve Hyman of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. That underestimation may in part explain why only a handful of drug treatments exist for patients with these diseases — almost all of them discovered by chance. The field desperately needs new tools to identify molecular mechanisms that can be targeted with drugs, as well as biomarkers to help researchers identify which patients might respond to a therapy and which might not. Evolving genetic technologies provide those tools, Hyman explained.

Psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have a heritably of up to 80%; depression has a lower, but still strong, genetic component as well. However, while some diseases are caused by mutations in a single gene, these diseases tend to be driven by variants of many genes, with no single gene playing an outsized role. Humans have been evolving for about 200,000 years and share many common gene variants. Gene chips can scan up to one million locations in the genome to identify common variants for a given phenotype — whether it be a feature such as height or a disease like schizophrenia.

In schizophrenia, for example, some 280 spots in the genome carry variants that can each nudge a person towards or away from the disease. Researchers can calculate approximately how much risk each gene confers. One recently developed metric called the polygenic risk score combines the weighted contribution of each of these risk genes for a given individual and compares them to a baseline to estimate the probability that the person will develop the disease. This score is the first objective tool for determining whether someone might be a good candidate for a clinical trial. “It will just get better as the genetics advance,” said Hyman.

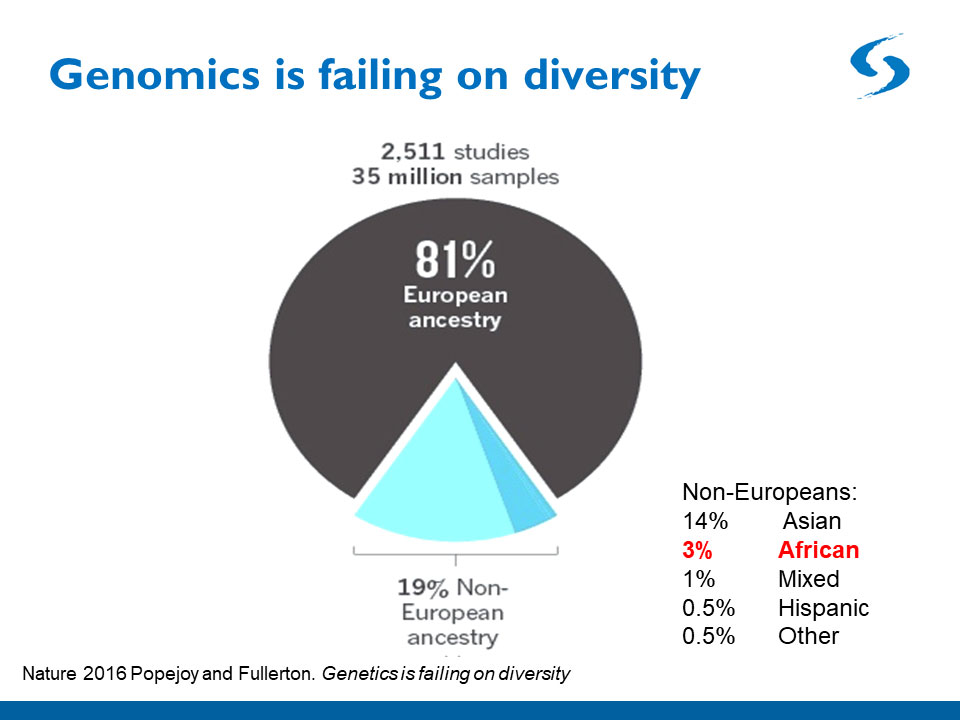

One problem with polygenic risk scores is that they are only as good as the population genetics data they are based upon. Most data come from white Europeans, so small deviations from the norm in that population are statistically detectable. But the collection of gene variants underlying a disease such as schizophrenia is likely to differ in people from Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin and South America, so the polygenic risk scores of patients from these backgrounds are currently much less accurate. Geneticists are beginning to amass more diverse data, but much work on this front remains.

Genetic analyses of common variants are beginning to yield cellular and molecular clues about schizophrenia. Risk genes are not all expressed in all cell types in the body, and analyzing variants in individual cells may reveal which cell types are most affected in the disease. Early work from another team at Hyman’s institute has found that more risk genes are expressed in a cell type called pyramidal neurons in the brain’s cortex. As the technology improves, researchers hope to develop a cellular map of disease risk. Researchers can then use stem cell technologies to make different types of neurons and study how the disease affects them. “There are many years of work ahead of us,” said Hyman, “but I think we finally have a toe-hold.”

Speaker Presentations

Further Readings

Nestler

Bagot RC, Cates HM, Purushothaman I, et al.

Neuron. 2016 Jun 1;90(5):969-83.

Peña CJ, Kronman HG Walker DM, et al.

Early life stress confers lifelong stress susceptibility in mice via ventral tegmental area OTX2.

Science. 2017 Jun 16;356(6343):1185-1188.

Blumberg

Johnston JAY, Wang F, Liu J et al.

Am J Psychiatry. 2017 Jul 1;174(7):667-675.

Edmiston EE, Wang F, Mazure CM, et al.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 Dec;165(12):1069-77.

Hyman

Brainstorm Consortium et al.

Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain.

Science. 2018 Jun 22;360(6395).

The Future of Therapeutics for Mental Disorders

Speakers

Wayne Drevets, MD

Janssen Research & Development, LLC

Maria Oquendo, MD, PhD

Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH

University of California, San Diego

Highlights

- Immune system molecules offer a promising target for novel depression therapies likely to help a subset of patients.

- Drugs already approved for other psychiatric disorders may be effective treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Studies point to at least two different phenotypes of suicidal behavior.

Neuroimmune Mechanisms as Potential Therapeutic Targets for Depression

Researchers know little about the underlying biology of mood disorders, so there is little to guide the field toward new treatments and biomarkers, said Wayne Drevets of Janssen Research & Development. However, emerging research suggests that some of the most reliable blood-based biomarkers for depression include immune molecules associated with low-grade inflammation, such as interleukin 6 (IL6), and proteins that react to inflammation, such as C-Reactive Protein (CRP).

Studies suggest that immune mechanisms play a role in roughly 33%–50% of patients with mood disorders, and that the adaptive immune system functions deficiently in depression. In a small subset of patients, autoantibodies to certain brain receptors and channels have been implicated in mood disorders. This suggests that at least some people with such conditions would benefit from therapeutics that target immunological mechanisms.

Several pharmaceutical companies formed a collaboration to explore this possibility (although currently, only Janssen and Glaxo SmithKline remain). Microarray data pointed to IL6 as a promising therapeutic target; IL6 levels remain high in people who do not respond to depression treatment and correlate with suicidality measures. They also predicted onset and severity of depression in children of parents with bipolar disorder. In animal models, antibodies against IL6 prevented depression symptoms in animals that experience a stressor.

The pharmaceutical company consortium pooled data from all trials to date and identified 18 trials that had drug targets and diseases with a prominent inflammatory component. Two of the tested drugs were Sirukumab and Siltuximab, Janssen compounds that target IL6. They then launched a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of Sirukumab as an adjuvant therapy in patients taking an antidepressant. The effects were not significant at 12 weeks, and a heightened infection rate in subjects suggested the need for a safer antibody or small molecule. However, additional analyses were encouraging. They showed that the antibody worked as intended, decreasing IL6 levels at the target, that the therapy did work in people with high CRP levels, and that a different, more sensitive depression measure hints that the treatment may work. “We do think this might be an important learning for future trials,” Drevets said.

It has long been unclear whether immunological therapies must work in the central nervous system or in the periphery to have an effect. To find out, the pharmaceutical company consortium is currently conducting a clinical trial of a small molecule that interferes with an ion channel called P2X7. The channel is expressed on the surface of brain cells called microglia and is activated by molecules produced by stress or inflammation. P2X7 activation causes depression-like behavior in animal models through the release of another interleukin called IL1-beta. Blocking the channel might therefore prevent stress-mediated IL-1beta release. If the small molecule works, Drevets said, it would validate the pursuit of central nervous system targets.

Neurobiology and Pharmacotherapy of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Although environmental factors often play a role in psychiatric disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the only psychiatric disorder that by definition involves exposure to a traumatic, life-threatening event, explained Murray Stein, from the University of California, San Diego. PTSD has four core features, but researchers calculate that there are more than 600,000 combinations of symptoms that can produce the disorder, and it often co-occurs with other conditions such as major depression and chronic pain.

Around 3% of people worldwide and 7% in the U.S. have the condition, but prevalence varies enormously by population. Women have PTSD at twice the rate of men, in part because of the types of trauma they tend to experience, and the rate for Native Americans living on reservations is 2–3 times that of the U.S. at large. Meanwhile, 30% of Vietnam veterans have the condition. Despite great unmet need, very few drugs exist to treat PTSD and none have been approved since 1999. However, certain psychotherapies do seem to help.

The lack of drug treatments may be partly due to a poor understanding of what causes the condition. Brain imaging studies suggest circuits involving emotional regulation, executive function, and threat detection is out of whack. Studies of soldiers deployed to Afghanistan and patients admitted to an emergency room have shown that traumatic brain injury sharply raises the risk of PTSD. Stein and colleagues recently showed in a small study that a drug called methylphenidate helps improve focus and alleviate hyperarousal in people with PTSD.

Using genome-wide association studies, researchers are beginning to identify genes associated with the disorder. Stein’s team led one such study, called ARMY STARRS, which found that a variant in a gene called ANKRD55 was associated with PTSD in African Americans. The gene’s function is unknown, but it is linked to multiple autoimmune and inflammatory disorders. He and others are collaborating with a large biobank called the Million Veterans Program in which DNA and survey results can be analyzed along with electronic health records. They identified a link between PTSD severity and the gene coding for corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1, which has already been associated with the disorder in other studies.

Finally, Stein noted that a few drug studies targeting dopamine receptors have shown promise, despite the fact that different studies have shown conflicting results. That could be because the effects of the drugs are uneven across PTSD symptoms, and therefore their benefits don’t register with the assessment tools used. Overall, he said, drug trials for PTSD have been limited, but combining genetics and bioinformatics may point to both new drugs and old drugs that deserve a second look.

Subtyping Suicidal Behavior: a Blueprint for the Development of Biomarkers

Maria Oquendo from the University of Pennsylvania described her work defining two distinct subtypes of suicidality. Suicide is a major epidemic, and identifying triggers and risk factors will help prevent deaths, she said.

The suicide rate varies widely between countries around the world, but overall, more people die by suicide (44,000 per year) than by automobile accidents (33,000). In the U.S., suicide has been on the rise since 1999. Some 5%–15% of the U.S. population experiences suicidal thoughts, and that number is thought to be much higher in adolescents. About four women attempt suicide for every one man; about three men for every one woman succeed.

Although nine out of 10 people who die by suicide have a psychiatric disorder, most people with a psychiatric disorder never attempt suicide — suggesting it is not enough to spur suicidality. Based on this observation, in 1999 Oquendo’s group proposed that some individuals are predisposed or pushed toward suicidality by behavioral factors such as aggression and impulsivity; mental factors such as cognitive inflexibility; biological factors such as dysregulated serotonin levels; or substance and alcohol abuse.

In 2004, they interviewed about 300 people with depression three months, 12 months, and 24 months after an initial evaluation. High levels of either aggression and impulsivity or pessimism greatly increased the risk of a suicide attempt, supporting their model. In a later study of 415 people with depression, 27% of participants had borderline personality disorder (BPD), so the researchers analyzed them separately. In people without BPD, both major depressive events and stressors such as health, work, and family events precipitated suicidality. However, in those with BPD, life stressors did not seem to contribute — perhaps because people with BPD experience life stressors in a way not captured by the study.

Nonetheless, the results suggest at least two independent pathways to suicidality. Oquendo and her colleagues hypothesized that one type of suicide attempter, who often has experienced childhood abuse, now struggles to regulate their emotions, reacts aggressively to threats or frustration, and has higher levels of cortisol and other biological stress markers. In such a person, life stressors would provoke suicidal thoughts, and they would attempt suicide impulsively. Another type of suicide attempter is someone tormented by recurring suicidal thoughts. Such a person is not impulsive or aggressive and has good cognitive control, but might attempt suicide in the context of a depressive episode.

Accumulating data supports the existence of these two suicidality subtypes. For example, people with high reactive aggression who were abused as children show sharp and frequent spikes in suicidal thoughts, often in response to seemingly minor life stressors; while people with low reactive aggression and impulsivity, have more stable levels of suicidality. Those with high aggression and impulsivity also have a spike in cortisol levels in response to a social stress test in the lab. And people with BPD who had attempted suicide seemed less able to engage brain regions involved in decision-making and perspective, suggesting a difference in their emotional regulation. There are some hints that differences in serotonin receptor levels may be at play in these two groups.

Oquendo believes there may be at least three other subtypes of suicidality, and her lab is trying to identify them in a study that follows patients with depression over a two-year period. Ultimately, the aim is to identify clear biomarkers for all suicidality subtypes.

Speaker Presentations

Further Readings

Drevets

Savitz J, Harrison NA.

Interoception and Inflammation in Psychiatric Disorders.

Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2018 Jun;3(6):514-524.

Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M et al.

JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 Dec 1;71(12):1381-91.

Janssen Research & Development, LLC, ClinicalTrials.gov.

An Efficacy and Safety Study of Sirukumab in Participants With Major Depressive Disorder.

Stein

Stein MB, Rothbaum BO.

Dire Need for New and Improved Therapies for PTSD: Response to Markowitz.

Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 1;175(10):1022-1023.

Stein MB, Chen CY, Ursano RJ et al.

Genome-wide Association Studies of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in 2 Cohorts of US Army Soldiers.

JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jul 1;73(7):695-704.

McAllister TW, Zafonte R, Jain S et al.

Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016 Apr;41(5):1191-8.

Oquendo

Bernanke JA, Stanley BH, Oquendo MA.

Toward fine-grained phenotyping of suicidal behavior: the role of suicidal subtypes.

Mol Psychiatry. 2017 Aug;22(8):1080-1081.

Rizk MM, Galfalvy H, Singh T et al.

Toward subtyping of suicidality: Brief suicidal ideation is associated with greater stress response.

J Affect Disord. 2018 Apr 1;230:87-92.

Addressing the Stigma of Mental Illness

Speakers

Jeff Lieberman, MD

Columbia University

Highlight

- Stigma surrounding mental illness is alive and well, but eliminating it would revolutionize mental health care.

Imagine There Was No Stigma of Mental Illness

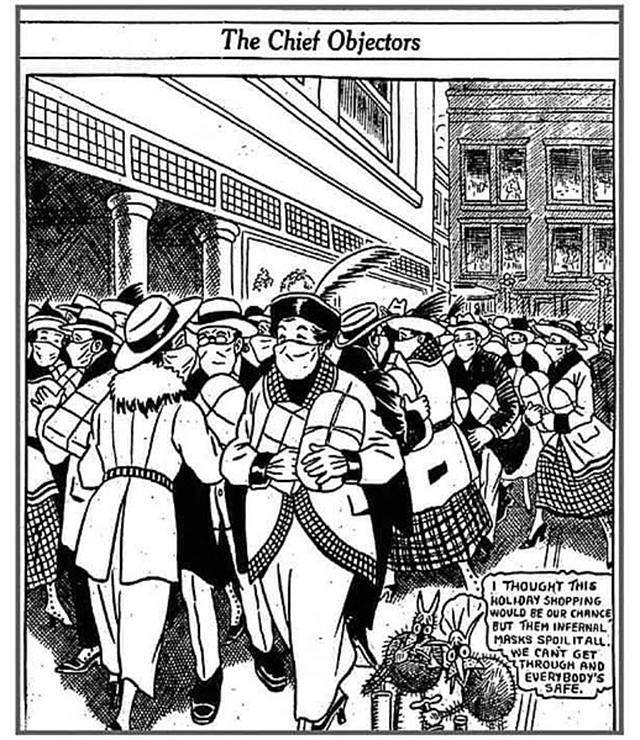

Suppose you had to give a toast for your boss at work one day, but you couldn’t make it because you were ill. Would you rather tell your colleagues you had a kidney stone, or that you were feeling suicidal? Jeff Lieberman of Columbia University opened his talk with this hypothetical scenario to illustrate that mental illness is still highly stigmatized.

Much of this stigma is driven by a decades-old skepticism and assault on the legitimacy of psychiatry, which came to a zenith when a doctor named Thomas Szasz — who wrote a book called the Myth of Mental Illness — joined forces with L. Ron Hubbard, inventor of an applied philosophy called Dianetics. The resulting belief system, Scientology, remains deeply opposed o psychiatry. The stigma of mental illness has real consequences — it is a serious deterrent to individuals seeking mental health care and has contributed a dysfunctional mental health delivery framework.

It also drives a funding disparity for mental health research. “If you do the math, 0.06% of the federal budget is spent on biomedical research that could advance our ability to understand and treat mental disorders and addiction,” Lieberman said — much less than for cancer, infectious disease, and cardiovascular disease. Because of that funding and attention, biomedical advances for these diseases made over the past several decades have led to effective treatments. Meanwhile, the World Bank estimates that by 2030, depression will be the most costly disease globally.

Medicine became a scientifically grounded endeavor in the 19th century and psychiatry formed one of he first professional organizations, now called the American Psychiatric Association (APA). At the time, the available tools limited progress in psychiatric research, and treatment for patients was often barbaric.

Psychiatry as a whole embraced Freud, and tried to apply his ideas to the broader population, despite the fact that they were irrelevant to specific illnesses such as schizophrenia and autism. “Theories were postulated that were preposterous and venal,” said Lieberman, such as that of the “refrigerator mother,” and overbearing parents as a cause of homosexuality, or orgone theory. By the 1950s and 1960s, when the number of patients in mental hospitals across the U.S. swelled to 550,000, the conditions under which most asylum patient lived were horrendous.

The turning point in the field’s validity came in the 1970s, when Columbia University psychiatrist Robert Spitzer was appointed chair of the APA’s task force to release the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (better known as the DSM, currently in its fifth edition). Although next to nothing was known about the biological basis of mental illness, he took a rigorous methodological approach, eliminating homosexuality as a diagnosis and describing post-traumatic stress disorder. The decades leading up to the 1980s were a scientific revolution of sorts, with the serendipitous discovery of psychotropic drugs and adoption of diagnostic methods. Today, it is a field wholly invested in scientifically driven methodology — the era of psychiatric neuroscience, Lieberman said.

It’s certainly possible to imagine eradicating the stigma surrounding mental illness — one stigmatized illness that succeeded in creating such a change is HIV. Without stigma holding back the field, and the institution of a health care system that provides mental health care from a public health standpoint, the results could be miraculous, Lieberman said. The system could target three distinct populations — the worried well, people with mild mental disorders such as anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and the severe mentally ill population — and offer them a variety of different avenues to care.

Speaker Presentation

Further Readings

Lieberman

Global Burden of Disease: Generating Evidence, Guiding Policy.

World Bank, 2013.

Shrinks: The Untold Story of Psychiatry.

Jeffrey A. Lieberman and Ogi Ogas. Back Bay Books, 2016.

Panel Discussion

Speakers

Hilary Blumberg, MD

Yale School of Medicine

Steve Hyman, MD

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

Jeff Lieberman, MD

Columbia University

Maria Oquendo, MD, PhD

Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

David Bredt, MD, PhD (Moderator)

Janssen Neuroscience

Highlights

- Complex chemistry and complex genetics are just two of the many challenges to developing drug therapies for mental illness.

- There is conflicting data about whether people with bipolar depression should be treated with antidepressants.

- The relationship between circadian rhythms and psychiatric disorders is poorly understood, but normalizing people’s sleep schedules may have therapeutic value.

The panel began by discussing the challenges in developing therapeutics for mental illness. Even in cases where the drug target is clear, the chemistry can be extremely challenging, said Hyman. There is also the issue of making sure the drug can be absorbed orally and then can cross the blood brain barrier. Also, he noted, psychiatric disorders are genetically very complex, and unlike cancers where researchers can identify a driver mutation to target with a precision therapy, many genes affected in psychiatric disorders converge on the same pathways.

On the other hand, said Oquendo, psychiatric illnesses have an advantage over cancer therapeutically, in that behavioral modulations can greatly help patients and can affect the underlying disease. In this field, she said, “there are many synergistic ways to skin a cat.”

In response to a question from the audience, Oquendo and Blumberg discussed the pros and cons of antidepressants for people with bipolar disorder. For a subset of patients, antidepressants might aggravate the condition, leading to a worse prognosis, Blumberg explained. Yet, if someone presents with depression, it is not always possible to determine whether they have major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder.

However, she noted, the literature is rife with conflicting data on whether antidepressants do in fact worsen the disease. Oquendo, meanwhile, said that the fear of giving bipolar patients antidepressants might actually have caused a good deal of suffering, and even suicides. In her experience, bipolar patients often strongly objected to being taken off antidepressants, and while epidemiologic and other studies don’t prove that antidepressants help, it’s not clear that they cause harm, either.

The panelists also discussed the role of circadian rhythms and sleep in bipolar disorder and other conditions. So far, chronobiological features have not been integral to the understanding of these diseases, but they may play a real role in their pathophysiology, said Lieberman. Researchers have long known that sleep deprivation can bring on a manic state, Blumberg noted, and shifting the sleep schedules of young adults with bipolar disorder often results in improvements to their condition. Another attractive dimension of targeting sleep and circadian rhythms, said Blumberg, is that “it’s a ‘do no harm’ intervention.”

Panel Discussion

Open Questions

How exactly does early life stress lead to behavioral changes in adulthood?

Can basic functions like sleep, daily rhythms, and energy levels serve as an early biomarker for bipolar disorder?

Can polygenic risk scores accurately stratify patients in clinical trials?

How should researchers design trials to test therapies that target immune molecules to treat depression?

How can genetics and bioinformatics data be combined to help identify new and repurposed drugs for PTSD?

How can researchers use accumulating knowledge on subtypes of suicidal behavior to develop effective interventions?

What can be done to eliminate the stigma of mental illness?